What does public participation in Nairobi look like?

The Constitution of Kenya 2010 requires the government – whether national or county – to facilitate and engage in public participation whenever making laws. However, the form such civic undertakings take depends on who is doing it, and why. For instance, when a sitting president wants to amend the Constitution through a “popular initiative” – as witnessed during the Building Bridges Initiative – no resources are spared and the whole affair more often than not culminates in an extravagant, closely-choreographed meeting at a packed Bomas of Kenya auditorium with hashtags flying and live TV coverage.

Certainly, you don’t expect a similar display of largesse during public participation exercises in the counties, yet these local governments ought to be best equipped to dispense information and receive views and complaints, given their distinctly local mandate. So Nairobi County’s Finance Bill 2023 was a chance for me to watch public participation in action, which was why the morning of 26 September 2023 found me at Kariokor Social Hall.

The meeting started late. County officials were suitably apologetic, but any employees who attended after promising their bosses that they would only pop in briefly were likely inconvenienced. Perhaps the County should explore scheduling meetings in the afternoon, when commuting is less of a challenge. Attendance would rise because it’s often easier to negotiate an afternoon off work if you’ve put in a good morning shift.

Chitchat before the meeting began showed a lack of information about county law-making. “Si mkatae?” (Why don’t you just reject it?) one woman who clearly had views but would not be speaking in public said. “Kama washaimplement?” (What if they have already implemented it?) The national government’s Finance Bill 2023 had dominated the news months earlier and some were not sure that it was not the same. “Hii ni ya Sakaja? So kuna ya Sakaja na ya Zakayo?” (This is Sakaja’s? So there’s Sakaja’s and Zakayo’s?) the same lady wanted to know, Zakayo, as in the Zacheus the biblical tax collector, being an unflattering moniker for the Head of State.

With half the allotted time gone at the start, the meeting was now a test of time management. A show of hands indicated that many attendees were from the Nairobi Central Business District, with some from South B, Kariokor-Ziwani, Ngara and Pangani. There was a sizable number of county government officials in attendance, all of whom were l introduced. All said, officials used slightly less than 1.5 hours on introductions, explaining the process and its importance, and reading through the Bill page by page.

We may pride ourselves on being digitally connected in Kenya but on that morning at Kariokor, print was clearly the most effective medium. Hard copies of the Bill were in high demand and residents were underlining numbers, writing comments in the margins and generally interacting with the Bill in a manner, one suspects, had not happened before. One gentleman pointedly refused to sign the attendance list, arguing that doing so would be endorsing the Bill, whose text he had only seen that morning.

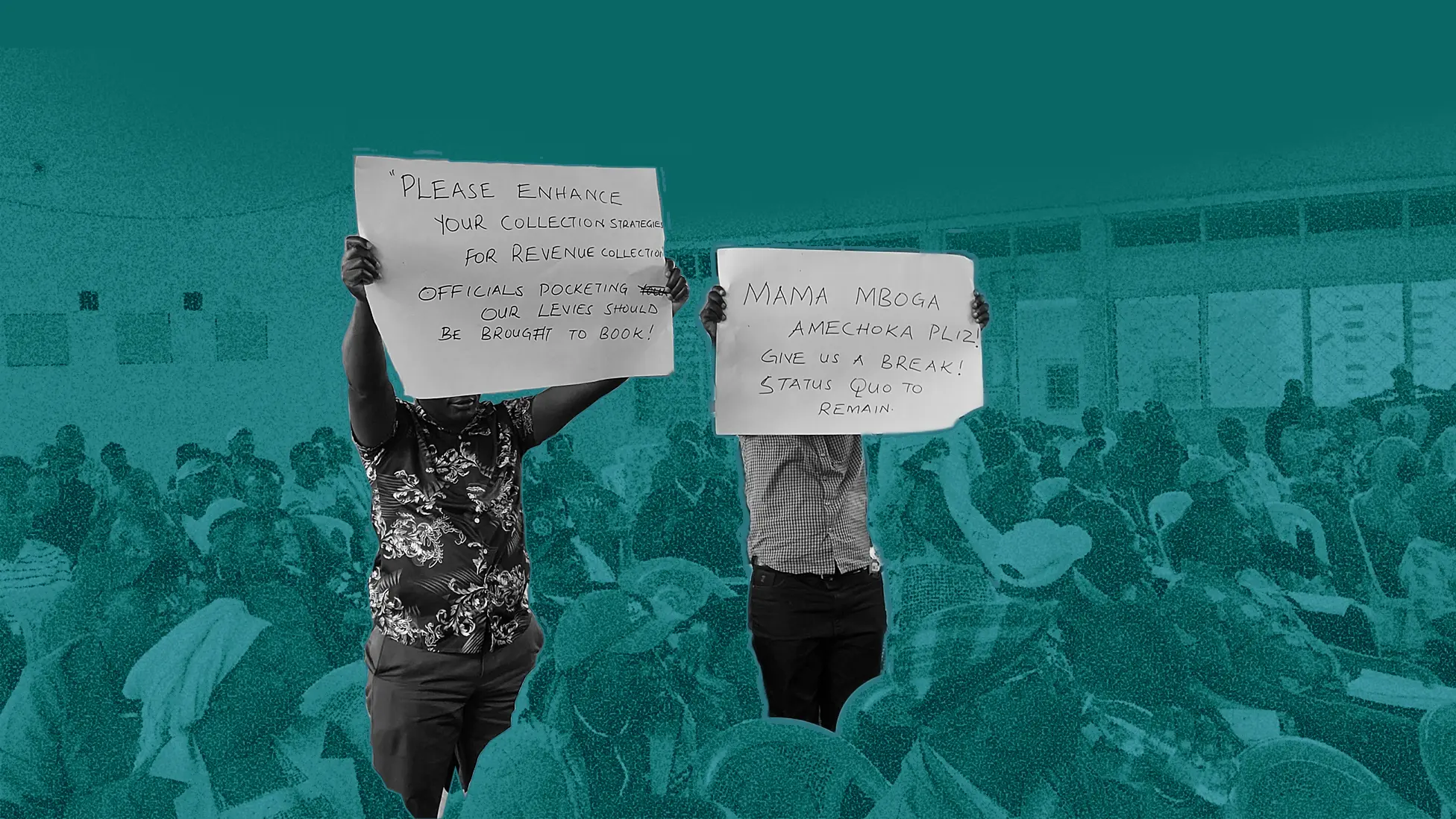

County officials had some successes. They made it clear that the Bill had not yet been passed and said residents’ views would be closely considered. Some messaging could have improved, though. Whereas they explained at length why the county needed revenue, most people in attendance seemed to understand why counties collect revenue. What they really needed explained was why those amounts and why now, when people were struggling. Some residents used placards to make their point.

One trader from Ngara I sat next to complained about a 30% increase in stall charges from KSh 2,000 to KSh 2,600. You may think KSh 600 a month isn’t a lot, but such amounts mattered here. One balding gentleman in dark glasses complained about public health inspection reports. “From nothing to KSh100,000. Hiyo ni kusema ufunge biashara (that’s like ordering you to close down). People will move to nearby counties,” he said.

The more earnest complaints came from market traders who claimed the additional charges were first, not justified based on the services they received and second, unfair. A man representing a group of chicken traders from City Market (let’s call him James) complained that the charge per chicken written in the Bill was KSh 10 instead of the KSh 5 that had been agreed at a meeting held in a Nairobi hotel , and that the previous charge of KSh 50 indicated in the Bill was inaccurate.

“How do you charge KSh 10 for a chicken and only KSh 300 for a cow?” “James” wanted to know.Yet charging by weight, KSh 300 for a cow amounts to a very good deal. “James” also complained about being charged for both the live birds and by-products such as gizzard.

A second trader, whom I will call “Joseph” said the traders needed support, not more taxes. “We are not doing business, we are surviving,” he said. “Joseph” also argued that the current fees regime favoured holders of single business permits at the expense of market traders. He claimed he was charged KSh 8,000 daily for one Canter truckload of onions. With three trucks each week, that came to KSh 24,000 weekly or about KSh 1.2 million a year in fees, a figure I could not verify at that moment. He challenged the County to show him a single business permit that cost that much, and proposed a lump sum instead of daily payments.

Another trader I will call “Peter” complained that the County taxed a single consignment of tomatoes twice; when it first arrived in Nairobi at Muthurwa Market, and then when it was sold again at Wakulima Market. “Do we have two county governments?” he wondered.

At this point, I chose to leave, but I came away with some thoughts.

A better meeting format would have involved placing the proposed fees on poster boards all around the venue from the start, so that residents could walk around and read what interested them as people arrived. Then, encouraging county staff to mingle with residents at this time would have allowed them to answer many questions, including those I have mentioned above. Obviously, those still unsatisfied could still have voiced their concerns in plenary.

Mobile broadband may work for social media and short videos but on this evidence, it’s completely unsuitable for reading 80-page unsearchable PDFs on small smartphones. What this public forum required was a searchable, abridged Finance Bill with a table of contents and lots of illustrations, both in print and online, along the lines of Treasury’s Mwananchi Budget.

The County’s clear video abilities would have made a difference reaching mobile internet users. Easily readable, annotated, searchable versions of the Bill, along with the original should have been available at sub-county offices, since not everyone travels to City Hall. After these meetings, the County Assembly should publish a public participation report to reassure residents that their views were accurately recorded.

So, to the verdict.

Public participation is happening in Kenya’s capital, but it can obviously improve. It must be more interactive, break down legal jargon and prioritise understanding, be mindful of time and provide information the way communities consume it.