“The revolution Will not be Televised” – Gill Scott Heron

Inasmuch as I do not exactly consider myself a logophile, words and word play have always intrigued me. Perhaps that is where my love for poetry, rhyme, and real-HipHop, early 90s especially, comes from. I enjoy it especially when words from different languages with similar phonetics (sounds) but different meanings can be used to interpret and mean something of similar inference in another language. This was not lost to me when my son, as a result to the recent attention grabbing maandamanos , asked me “Daddy, what is mandamos?’’ His mispronunciation swiftly sent my mind to the Latin word and legal concept of mandamus – a writ or order issued by a court directing a person to perform or repair the misperformance of a duty or obligation.

Considered within the effects of the recent Kenyan maandamanos that eventually ‘urged’ President William Ruto and the government to call for bipartisan talks effectively made maandamanos a mandamus of sorts (more on this below). Another example of such word play is when Yaniv Roznai played around with the English word “we” and the French word “oui” in the title of his article “We the People, ‘Oui the People’ and the Collective Body: Perceptions of Constituent Power”.

Après Moi…

Through this device, Roznai successfully communicated the notion that at the end of the day, in constitutional democracies, power (consent) resides with the people. Another example was when in December 2002, on the eve of Kenya’s general election, and when President Daniel arap Moi’s rather unpopular term as president for 24 years was ending, the Guardian newspaper ran an article titled “Après Moi, the Delusion”. The title was a play of words, whereby the French word “moi” which means “me” in English, and the name Moi were punned around the phrase attributed to Louis XV of France – Après moi, le delugé (After me, the floods).

Conceitedly, and as the legend holds, Louis XV (also aptly referred to as Louis the Beloved) made this remark to imply that he was the personification of France. France was him and he was France and his departure from the throne, by whatever reason, would spell doom (deluge-floods) to the kingdom. And perhaps he was justified to allude himself with such grandeur, considering that his largely regarded corrupt and wasteful reign of 59 years was only second to that of his predecessor, Louis the VIV, who reigned for 72 years.

Handed a poisoned chalice, Louis XV’s successor – Louis XVI – would become the last King of France. His reign, cursed by his predecessor and that of French kings, ended violently. This was due to his predecessor Louis XV’s and his own extravagances, which 15 years in would send the country into the now famous 1789 French Revolution, which capitulated the then phase of French monarchy.

Yote Iliwezekana Bila Moi?

Similar to what the French Revolution must have meant to the French hoi polloi, President Moi’s departure and the imminent defeat of his preferred candidate, Uhuru Kenyatta, which would also occasion the dethronement of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) – in control since independence – must have felt in Kenya in 2002 the way it felt in France on the eve of the revolution. This mood then was appropriately scored by the then ubiquitous opposition mantra and song “Yote yawezekana bila Moi”, which myopically suggested that Kenya’s only problem was Moi, and therefore his departure was the only solution (hence the sceptical title and article by the Guardian, which based on the analysis of the politics and opposition politicians who were about to take over, reckoned that the optimism by Kenyans, was at best, a misapprehension).

Twenty years later, the post-Moi ‘yote yawezekana’ utopia is yet to be realised.

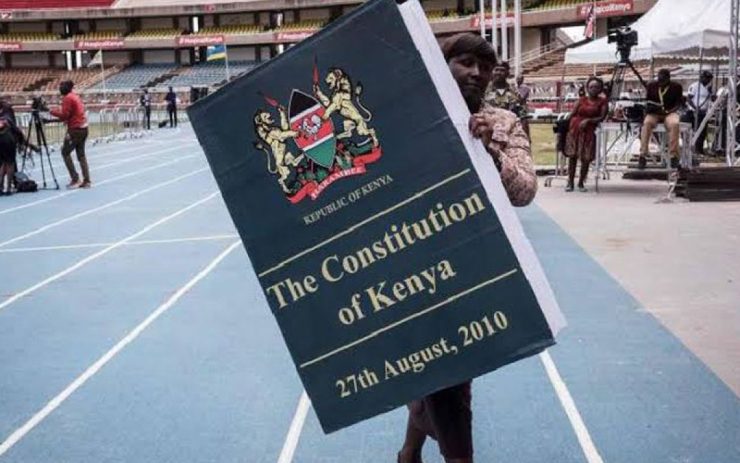

Granted, some motion has been made, albeit more in distance than in substance. For instance, inasmuch as the country realised a new constitution in 2010, errors of the Moi era, which the Constitution was meant to repair, still abound. A case in point are the recent maandamanos. What were supposed to be the constitutionally designed peaceful protests turned out to be a front for the state to violently clamp down on protestors (or pretenders) and for thugs (the pretenders) to infiltrate demonstrations in order (or disorder?) to destroy, maim, steal and rob.

To an extent, this turn of events was frustratingly expected particularly when one goes down the memory lane of Kenya’s maandamanos, especially during the struggle against Moi’s and KANU’s one-man/party dictatorship. The violent ways through which Moi’s regime dealt with demonstrations and protests was the very inspiration for Kenyans to specifically include the freedom of assembly, demonstration, picketing and petition, in addition to the related freedoms of association, expression, and political rights. In addition to its vitality in the democratic society that Kenyans were striving for, from experience, they had also learnt the hard lesson that as J.F. Kennedy said, “Things don’t happen, they have to be made to happen”.

If freedom wasn’t specifically woven into the constitutional fabric, its use would remain unhemmed and patchy.

Usitoke Kwa Nyumba!

Belabouring the Moi period, it can be argued that if the cumulative gains between the late ‘80s and 2002 – reintroduction of multiparty politics in 1992; the Inter-Parliamentary Parties Group (IPPG) process that injected some reforms prior to the 1997 elections; and the commencement of an inclusive constitutional review process culminating with the ousting of Moi and KANU, – are assessed, then one can deduce that the algorithm of maandamanos in Kenya is programmed to occasion opportunity, not to blackmail the government, but wananchi, especially those in Nairobi, the country’s and region’s nerve centre. This by creating in them the spectacle of fear.

The only other thing that Nairobians fear as much as maandamanos is rain! To them, maandamanos invoke a siege mentality of sorts, which leads to self proclaimed curfews, logically actionable by one thing only – usitoke kwa nyumba! This leads to people shutting their businesses, not sending their children to school, working remotely (for the few who can), or simply choosing not to venture out of the safety of their houses. The city becomes crippled and a ghost-town of the living (pun not intended).

Regrettably so, there are many – arguably the passive majority – whose ugali is pegged on daily wage gigs, who eventually sleep hungry because during maandamano days, they earn much less or nothing. Whereas the government can withstand a few days with less revenue resulting from depressed collection of fees for services and other taxes (Nairobi loses c. KSh 40 million (as per its Governor) and the national government KSh 2 billion (as per the Deputy President) on each maandamano day, most ordinary wananchi cannot.

Oui!

The maandamano-induced agony, garnished with the images of youth in running battles with police, tear gas and stones battling the airways, burning tyres on roads closed by goons beamed live onto the screens of fear-laden Kenyans is designed to, using Walter Lippmann’s notion, manufacture their consent because what invariably follows is their support for the choral calls where the diplomatic corps and persons of the cloth playing soloists, for dialogue!

This manufacturing of consent (Roznai’s ‘oui’) through the engineering of mass fear is the maandamano model in Kenya; based personified by a scarecrow. If not, why are they announced and perceived as threats? Political demonstrations in Kenya are not designed to ideologically sway the support of the masses through the cogency of the issues communicated as their causes (e.g. the cost of living) but to break them into submission resulting from the fear of the threat to their livelihoods.

In a sense, maandamanos are meant to procure public ‘oui’ through ‘coerced conversion’.

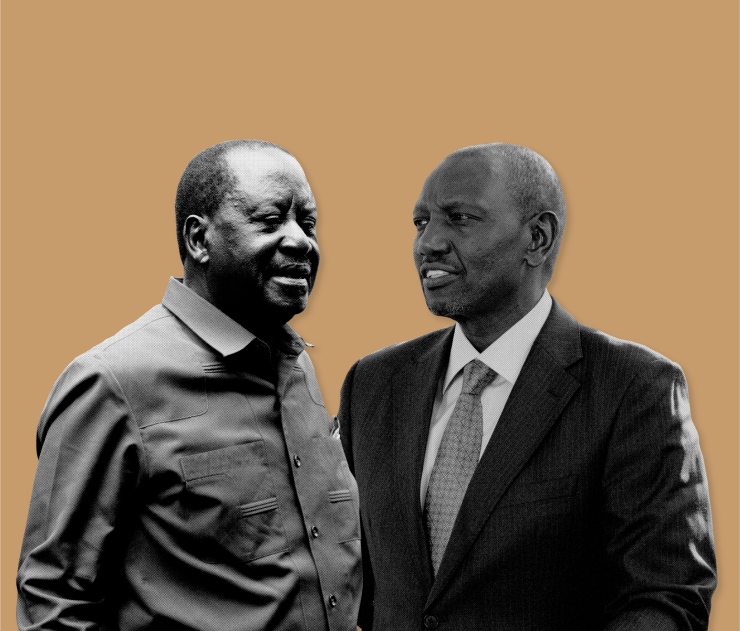

Ultimately, it is the state of the suffering of the people, especially the one occasioned by the maandamanos, that is used as leverage by politicians to get together and negotiate their political interests. Peoples’ interests are used as Trojan Horses for securing narrow political interests. This explains why, when both President Ruto and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga made their announcements about their rapprochement, electoral justice and not the cost of living was the primary concern.

For Odinga and Azimio, round one of maandamano (round two expected after Ramadan) was a success (hence the threats for phase two) considering that, when looked at from a return of investments perspective and empirically, Round One demonstrations directly involved (those who went to the streets) only a small minority of Kenyans, and took place in a few sections of the country, mainly in Nairobi (Kibra, Mathare, Kawangware) and in the western (former Nyanza province and Odinga’s support base) belt of Kenyan counties.

Usituuzie Uoga…

The fear dividend was enough to cause the President and government, and commendably so, to ‘hastily’ agree to have bipartisan talks. Not that the President and government, as primary duty bearers, were innocent bystanders – completely outmanoeuvred and could no longer conscientiously bear the weight of suffering Kenyans – but it was in itself an interested party because out of the demonstrations, they also scored a few goals.

Not only did the government manage to halt maandamano, hence buy time and deflate Odinga’s and Azimio’s momentum, it also managed to expose and forment the narrative, which President Ruto is on record stating, that Odinga and Azimio were not demonstrating because of Wanjiku’s interests but their personal political gains.

The President’s communication that the solution to what he and “his brother” Odinga had deduced as problematic during the current wahala, during their unannounced private tete-a-tete held before the announcement, was bipartisan talks, beholden to the narrowed Parliamentary scope of politics, couched in the majority (currently also government side) and the minority (current opposition) dichotomy, also managed to circumscribe the agenda, and perforate Azimio’s propaganda bubble and wriggle room.

The announcement and what can now be termed as the Ramadan maandamano ceasefire bought time for the government and allowed it to deal with what would be deemed as the people-centred moral issue and authority for the demonstrations – the cost of living. For the majority side, the pluses have been that since then the President has announced the falling of the price of unga and the maandamano spectacle managed to divert attention to what was then brewing to be the major political hotcake – the unpopular and controversial appointment of 50 Cabinet Administrative Secretaries (CAS).

In the interim, the government has also managed to use the maandamanos not only to invoke and display what Max Weber described as the state’s “monopoly on the legitimate use of force” (and in its own way invest its stake in the market of the commodity of fear), it also managed to add capital to its counter-propaganda that Odinga and Azimio were organising the maandamanos not for altruistic but for personal interests.

Constitutional Review

Further, it can also be argued that the President may have used the maandamanos to cultivate justification and build political momentum and consent for discussions around his proposals for constitutional review. This is because in addition to him announcing the bipartisan talks, guiding that the discussions around the renegotiation of the reconstitution of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) – the only item, which was according to him was legitimate and worthy of talks, out of Azimio’s retinue of maandamano lamentations – could only be discussed within the confines of the current legal and constitutional framework (meaning the ongoing recruitment of IEBC commissioners can only be legally paused through judicial action and/or legislative revision, and not arbitrarily or administratively), suggesting that the issue could optimally find repair if discussed within the wider scope of his proposals for constitutional review.

In a sense, Azimio has handed the President the perfect opportunity not only to control the process of these current talks (process, timelines, institutions, structure), but also the agenda. Eventually, it should not be surprising and ironic that out of a tactic birthed by Odinga and Azimio for their own political advantage, it is President Ruto’s and Kenya Kwanza’s proposals for constitutional reform that will eventually become centre stage during the anticipated talks, bipartisan or otherwise.

It can therefore be validly argued that during the current season of maandamanos, both government and opposition are using the by-product – fear, to gain political mileage. To this effect, peaceful maandamanos as prescribed in the Constitution are not in their interest. For the government, the risk of what may transpire when throngs are allowed to pour into the streets is not worth the gamble. That is why the other day, while meeting H.E. Abdulswamad Sharrif Nassir, the Governor of Mombasa, Muslia Mudavadi, the Prime Cabinet Secretary (PSC) pointed at the deteriorating state of security in neighbouring Sudan as an example of where the country may head towards if maandamanos are allowed.

The al fresco display of state brutality, though bad publicity (which is also good), served to remind Kenyans of its authority hence investing further into the commodity of public fear. For Kenya’s current opposition, peaceful maandamanos, even those where multitudes pour out into the streets, may not form good content and register optimally in media, foreign and international especially. If without controversial incidents, the maamdamanos stand to be treated like ordinary political rallies, whose optics and acoustics do not resonate as well as those of the chaos delivered by a maandamano gone awry. That is why during the run up to the 2022 elections and previously, normalcy sustained despite the tens if not hundreds of massive political rallies that were organised and held across the country. Kenyans do not fear peaceful mammoth crowds. They however fear a small group of stone-carrying and stone-throwing youths, teargas and clobbering by the police. Like rain, that will stop them in their tracks.

Si Waongee Tu…

Out of this fear that maandamanos shall be unleashed on them, the public (silent majority) is held hostage and only left to inadvertently offer their consent through the Stockholm Syndrome oriented si waongee tu appeal; the street-wise version and backing of the earlier mentioned efforts by diplomats, faith leaders, entertainment celebrities and prominent business personalities who using rhetoric and backroom meetings term as dialogue.

Observing the build up to Kenyan demos, and the recent ones for that matter, it can further be validly argued that both sides, the government and organisers, which in most cases is the political opposition, actually ‘plan’ for the chaos. This through rhetoric (demonstrations as threats and the conditioned association of demonstrations with chaos); the deliberate refusal or neglect to follow the law (disputes over technicalities like notifications and eventual stand-offs which the police use as the excuse for clobbering ‘law-breakers’); and outright ‘war-cries’ (“mother of all demonstrations” Vs. “Government shall assert its authority”).

With this recipe and ingredients, and knowingly so, the current maandamano algorithm can only deliver street-battles, which are used to brandish fear so that wananchi can be pushed into submission and start appealing for talks of whatever nature, because when politicians sit to talk, wananchi can walk, hence work in peace.

Maandamanos are hence used to exploit the moral authority and consent of the people, especially so for the facilitation of politicians’ self interests. Without chaos and fear, it would be hard for politicians to justify and explain why they are clamouring for or holding talks to negotiate their political interests. But out of the public fear of maandamano, like the delusion of Moi’s departure, all becomes possible. After all, as Michel Foucault stated for supposed liberal governments like Kenya’s, the “…simulation of the fear of danger is… the condition, the internal psychological, cultural correlative of liberalism. There is no liberalism without a culture of danger.”