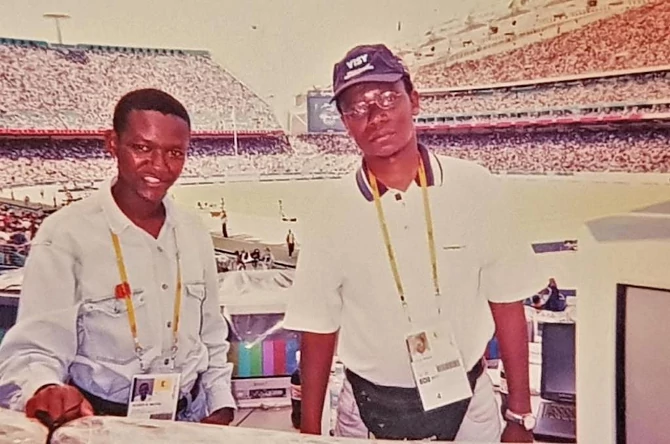

In the year 2002, Dr. Alfred Mutua was in the middle of one of his most adventurous journalistic assignments when he received a life changing email. During the 2000 Summer Olympics held in Sydney, Australia, Equatorial Guinea’s Eric Moussambani made history by being the slowest swimmer in the 100m freestyle, taking a whopping two hours to cross the finish line. Yet due to false starts by his two competitors, Moussambani won the heat and was christened Eric the Eel. Mutua was dispatched to Equatorial Guinea by an Australian TV station to go and interview The Eel.

After graduating from Wentworth University with a BA in Journalism, Mutua had earned a scholarship to the Easten Washington University, where he obtained an MSC in Communication, topping his class. Mutua then returned to Kenya in 1997 and took up a teaching job at Daystar University, where he was the youngest lecturer at 27. On the side, Mutua doubled as a correspondent for the Nation Media Group, where considering he was paid per article, he wrote features almost every other day of the week, earning more money than some full time scribes. Mutua needed all the money he could make.

‘‘When I came back from America, I found my family had moved from Riruta Satellite to an even worse place in Kangemi, and so I moved them back to a better place in Riruta,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘While in America, I had the choice to either study and stick to the limited permitted working hours, or work illegally and get deported, which wasn’t an option.’’

It was while teaching at Daystar and working at the Nation that Mutua received five PhD offers with funding; Indiana University, Illinois State University, Leeds University, the University of Sheffield and University of Western Sydney. Mutua picked the University of Western Sydney, on the basis that as a 15 year old at Dagoretti High School, one of his teachers, Z.G. Wanja alias Big Fish - Mutua says he was a bulky man, had travelled to Australia and come back with a 30 minute long tale of his exploits for the school. Mutua vowed that he too had to go to Australia. That’s how he still makes his decisions, quick.

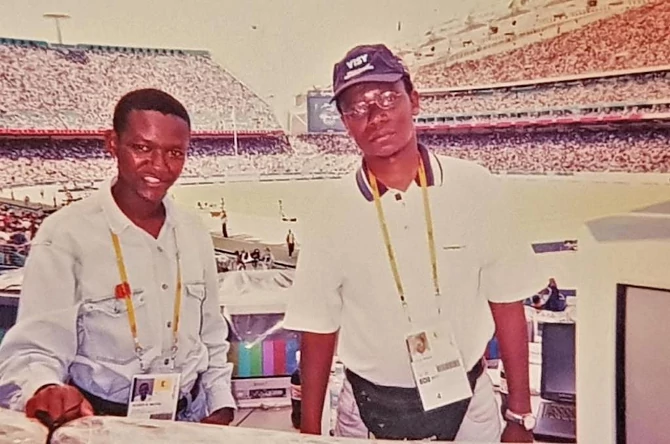

While studying in America, Mutua had taught himself filmmaking online, since both his undergraduate and graduate degrees didn’t cover electronic media. But once in Sydney, Mutua went all out, including attending the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS). And from that point onwards, Mutua became a one man army, travelling to do projects either on self assigned missions or for the various TV stations he was working for as a stringer. Mutua set up the lights, operated the cameras and did the interviews.

‘‘I was one of the first people to interview Joseph Kabila when he became president of the Democratic Republic of Congo,’’ Mutua says, and goes on to share tales of how it was a common occurrence to be approached by women in Kinshasa, asking, ‘‘Uko na bibi? Hapana Kenya. Uko na bibi hapa?’’ And if one said no then they’d say, ‘‘Sasa kuanzia leo mimi ni bibi yako.’’ But beyond the possibility of one getting married the moment they land in DR Congo, Mutua has nothing but praise for the city of rhumba.

It was under these circumstances - of moving all over Africa and elsewhere, like that time before New Year’s in the year 2000 (the turn of the millennium) when Mutua travelled by road from Nairobi to Harare making a documentary - that Mutua found himself in Equatorial Guinea in search of Eric Moussambani alias Eric the Eel. But after making the journey through Douala, Cameroon, and flying into Bioko island which hosts Malabo, Equatorial Guinea’s capital, Mutua couldn’t locate The Eel - who would later become his country’s swimming coach - because he had apparently travelled to Nigeria.

‘‘One evening I was coming from shooting a soccer game, and when I got back to my hotel room in Malabo, Don Roberto, the hotel security guard didn’t receive me with the usual excitement I had come to expect from him,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘When I got to my room, I found the door open with two suited men with shades seated on my bed watching the TV. The room looked ransacked. They asked me to pack my bag and accompany them, and didn’t entertain any queries. I was sandwiched at the back of a Mercedes Benz which drove on the main highway towards the airport. I knew I was being deported.’’

The Mercedes Benz stopped at a highly fortified compound. Mutua was asked to step out of the car and strip naked. He obliged. He was then asked to dress up and pick up his camera. Once inside the compound, Mutua was led to a tennis court at the back of what he says was a resplendent mansion, where he found an old African man and an Asian man exchanging groundstrokes. The Asian man was faring badly. After they were done playing, the old African man came at Mutua cheerfully. That man was Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea’s President for Life. Obiang’s people had caught wind of the African journalist working for the Western press, and wanted their man to receive some coverage. Mutua was relieved. At least he wasn’t being deported.

It was after this incident that Mutua checked his email and found an invitation to go and teach Communication in the United Arab Emirates, an offer that was too good to resist. Mutua went back to Australia, wrapped up his PhD, bid goodbye to his employers and took off to Dubai, a vantage point from where the Kenyan government would spot him.

‘‘I visited Kenya in 2003 and passed by the Nation Media Group, where NTV was having hitches using a program called Final Cut Pro,’’ Mutua says. Wangethi Mwangi and Cyrille Nabutola were the incharges, and Mutua says he told them that whatever they were struggling with was what he was teaching in Dubai. ‘‘Wangethi Mwangi gave me a consultancy where I came to Kenya every month for 10 days. They’d put me up at The Stanley and pay me really well. I also got a writing slot in the Sunday Nation.’’

It was as Mutua was minting petrodollars as an assistant professor of Communication in Dubai and simultaneously munching the Nation’s shillings that he received a phone call from Rebecca Nabutola, who was the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Tourism.

Nabutola: Are you Alfred Mutua?

Mutua: Yes.

Nabutola: In that case please call this number.

Nabutola gave Mutua the phone number. Mutua called. The recipient was Raphael Tuju, the Minister for Tourism, Information and Communication. Tuju was at an event, and told Mutua to send him his Curriculum Vitae. A few months passed. Mutua didn’t hear back from the Minister or the PS. Then one Friday evening as Mutua was driving in Dubai, he received a call from the Office of the President inviting him for an interview slated for the following Monday at 8am. By this time Mutua had gotten wind that President Mwai Kibaki’s government was looking to establish the Office of the Government Spokesman.

Mutua’s next visit with the Nation Media Group was a week away, but seeing a chance to kill two birds with one stone, Mutua called the Nation and asked them to send him an air ticket, saying he wanted to conduct that month’s consultancy earlier than anticipated. The Nation sent their man the ticket. Mutua landed in Nairobi that weekend, only to find that across all the Sunday papers, the man being touted as the incoming Government Spokesman was the New York based Salim Lone, the one time subversive editor of the Sunday Post and later on Viva Magazine, who was a Communications Director at the United Nations. Lone knew the job was as good as his, and had resigned from the UN.

‘‘On Monday morning I went to the Nation Center, prepared my CV and other paperwork - I had written down ideas on what I would do as Government Spokesman,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘From there I went to the Office of the President, and was surprised when I saw interviewees arriving as late as 9am. Sitting there, I saw ministers streaming in, and at around 9.30am, an old man came and asked who had arrived first. The secretary said it was me. I was ushered into the interview room, where I found a number of ministers.’’

Mutua says he went in, did the interview - he was asked to converse in Kiswahili too - after which he drove to Masii to visit his grandma. As Mutua was driving back to Nairobi that Monday evening, his long-aerialed Sony Ericsson phone rang. It was Raphael Tuju calling. Mutua picked the call. Tuju informed him that he’d been hired as Government Spokesman, and asked him to report to the then Head of Civil Service Amb. Francis Muthaura first thing the following morning. ‘‘Tuju told me that after I had left the room,’’ Mutua flexes, ‘‘they wondered whether they needed to interview anyone else.’’

That Tuesday morning, Mutua went to see Amb. Francis Muthaura on the seventh floor of Harambee House as instructed. After getting the preliminaries out of the way, Amb. Muthaura told Mutua they’d send him an offer letter, asking when Mutua was ready to start. Mutua informed him that he couldn’t start immediately since he had students in Dubai and he needed at least three months to finish the semester with them, something which Mutua says Amb. Muthaura was greatly impressed by. ‘‘He was very happy,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘because he saw a man who wouldn’t simply walk out of a job because he got another. He told me to go and finish teaching the course. That they’d wait for me.’’

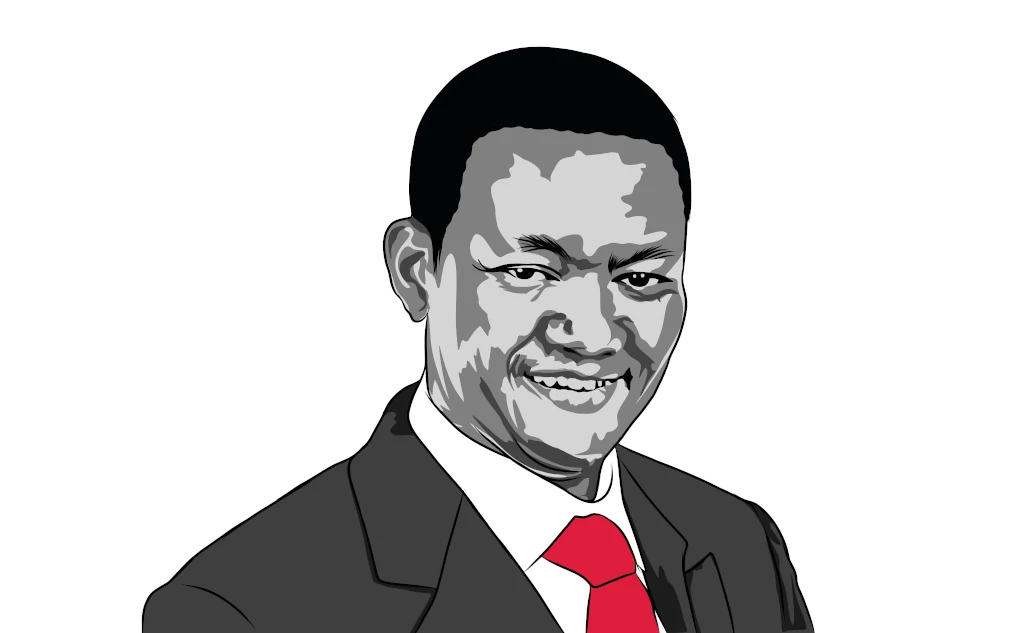

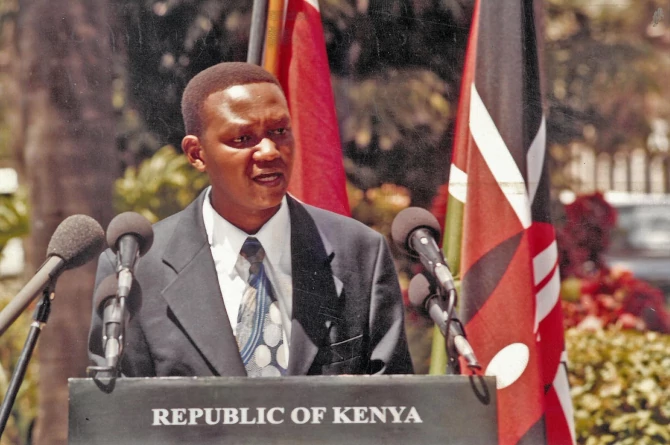

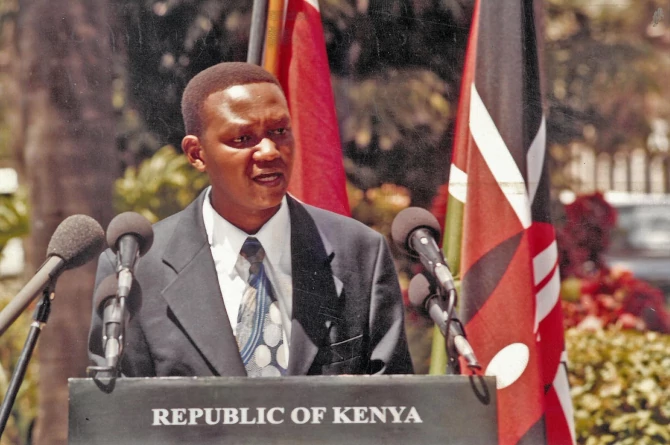

Mutua went back to Dubai, leaving Nairobi abuzz with speculation that the job was Salim Lone’s. In June 2004, Mutua jetted back into Nairobi ready to embark on his new assignment, and was put up at the Intercontinental by the exchequer. The following morning after Mutua’s arrival, he was picked up and taken to State House to meet President Mwai Kibaki. ‘‘Kibaki told me two things,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘Pick very good staff to work for you, and always speak the truth.’’ From State House, Mutua was chaperoned to Harambee House, where he was unveiled as Kenya’s first Government Spokesman.

And so began Mutua’s tenure as Amb. Francis Muthaura’s conspicuous shadow.

‘‘It took people by surprise when the announcement was made that I was the new Government Spokesman,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘and everyone started wondering who was this young boy? Senior editors and renowned journalists had all been bypassed, and so even I asked myself why me? I knew nobody. I had no godfather in government. ’’

Mutua was 33 years old.

‘‘I was thrown right into the fire because I came in at the time of Anglo Leasing, and there were some efforts at a cover up by some people, with John Githongo blowing the whistle,’’ Mutua says, but adds that he won’t spill the beans just yet because his tell-all autobiography is in the works and will be hitting the shelves soon. ‘‘I would speak and people within government would contradict me, because they weren’t used to the idea of having an official spokesman. But I kept going, and strictly took my briefs either from President Mwai Kibaki’s office or directly from Amb. Francis Muthaura.’’

And here, Mutua throws in a caveat, albeit belatedly.

‘‘I never made any personal statements,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘Everything I said had been discussed and approved, and so whether someone liked or disliked whatever I said, the fact remains that those were the statements sanctioned by government.’’

But as I speak to Mutua it becomes clear that he wasn’t just a mouthpiece or conveyor belt for what the big boys and girls in government wanted him to pass on to the public.

For starters, Mutua volunteers that he attended a sizeable number of daily briefings given to President Kibaki, in which instances Kibaki would show up and ask in that Mwai Kibaki-voice, ‘‘Haiya, dunia inasema nini?’’ It is an open secret that this was the purview of the National Intelligence Service (NIS), and in a different context Mutua submits that he and Michael Gichangi, the NIS Director General, had a cordial working relationship.

Aside from the highly classified briefings, Mutua shares that he was in the room when government was being formed or reshuffled, like in 2005 after ministers were fired for opposing the draft constitution, or in 2008 when a government of national unity was being put together. Mutua says he was the one taking minutes during such meetings, and that beyond just being a fly on the wall, he’d be given opportunities to share his thoughts. ‘‘I was a Kibaki insider,’’ seems to be what Mutua is saying, and none of this could have been possible had it not been for Amb. Francis Muthaura, who Mutua calls his mentor. ‘‘He’s one man who held this country together,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘and I learnt from him how a government should be run and how not to run a government.’’

It was while being Amb. Muthaura’s shadow, Mutua says, that he ended up drafting the earliest notes of what became Vision 2030. After a meeting of Permanent Secretaries who were being familiarized with Singapore’s practice of setting development targets in the form of visions, Mutua and Muthaura retreated to Harambee House where Muthaura asked Mutua to draft something. Mutua says he drafted what he termed Vision 2020, which he took to Muthaura, who made some changes before they took it to Kibaki, who made more changes before McKinsey & Company were roped in to design the full breadth of the project. ‘‘It is McKinsey who turned it into Vision 2030,’’ Mutua says.

Then there was the allocation of national projects, which Mutua speaks about as if it was the splitting of a goat among friends. Mutua says he wanted the proposed technocity to go to Machakos, Mua Hills to be specific, because he owned a farm nearby - he says this in that I-am-joking-but-I’m-not way he speaks sometimes. Mutahi Kagwe, the then Minister for Information and Communication, wanted the technopolis to be situated in present day Tatu City. Eventually, with the support of Muthaura, Mutua carried the day and the technopolis was taken to Machakos, first to Lukenya, but since the locals wouldn’t sell off their land, the city was transferred to Konza.

On his part, Mutua says Amb. Muthaura wanted the resort city to go to Isiolo, because it was closer to his rural home in Meru. But what was more dramatic was the night when Mutua had to go in search of a map at 3am in the morning, because they couldn’t agree on whether a port should be built in Lamu. Mutua says everyone in the room including President Kibaki wanted the port built at Dongo Kundu in Mombasa, but that it was Stanley Murage, the president’s special assistant, who argued for Lamu. Mutua brought the map, Murage made his viability case and everyone in the room was convinced.

This is how a country is run.

But then there’s Mutua’s fascination with Lucy Kibaki, the First Lady. By all indications, Mutua may not have had a godfather, but his reverence for the former First Lady shows just how much she liked having him at State House. First they started out with the First Lady asking Mutua to design a seating chart for all national celebrations, an assignment Mutua says he carried out with the assistance of the NIS Director General. Then there was the 2005 referendum, where Mutua says the First Lady called him to be in the room as she interrogated those who were leading the YES Campaign, telling them how they were siphoning resources out of the campaign while their opponents were riding to victory. ‘‘They tried to argue with her,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘but Mama Lucy told them she had her ears to the ground, telling them she was sure the government would lose 60% to 40%. It came to pass.’’ And yet what really stood out for Mutua was how the First Lady ran a tight ship at State House, never allowing the free flow of food and drinks since the President was on a super strict diet. To Mutua, this alone saved Mwai Kibaki’s life.

‘‘We’d have lunch with the President,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘and he’d have two drumsticks, a banana or an apple and water. That was it. No juice. No soda. No starch. This is what kept Kibaki alive, because were he to crave the steaks he was used to and so on, and were he to have them, then he’d have messed up his diet and possibly developed complications.’’

I ask Mutua what his lowest moment was as Government Spokesman.

‘‘I remember someone calling me while I was sitting with Police Commissioner Maj. Gen. Hussein Ali and Amb. Francis Muthaura,’’ Mutua says, referencing the 2007/2008 post election violence. Incidentally, Muthaura and Ali would initially be listed as suspects set to appear before the International Criminal Court at The Hague on grounds that they’d played a role in the violence, before they were let off the hook. ‘‘The person was crying on the line, telling me they were under attack somewhere in Naivasha. I told the Police Commissioner, who started making phone calls. But as this was happening, the person kept calling, saying the attackers were drawing closer, that they were killing people nearby. Eventually, the caller was killed. The police were not taking orders.’’

All said and done, Mutua says what kept him close to the center of power was his absolute loyalty to Kibaki and consistency on whatever they had agreed upon.

‘‘I am not a watermelon like some people in this country,’’ Mutua jibes.