This is not what this story is about. But once upon a time, Justin Muturi and Uhuru Kenyatta used to catch pints together, often. Maybe they still do. Maybe they don’t. Or if they still do, maybe they don’t share a drink as often as they used to. Muturi doesn’t tell me any of this. He really says little about his well-known conviviality with President Kenyatta, even when I try to prode harder. I hear this from a former Member of Parliament who had occasion to hang out with the boys back in the good old carefree days of their first and second terms in Parliament.

After opting out of the Judiciary in 1997, Muturi went back home to Kanywambora, from where he launched his parliamentary bid for Siakago Constituency on a KANU ticket. Silas M’Njamiu Ita - a man who had pulled himself up by the bootstraps and who Muturi admired greatly and even campaigned for previously (he’s also the man whose name keeps popping up in the Tob Cohen murder case, since he was business partners with Cohen) - won the seat. The backstory is that Ita had originally wanted to run on KANU, but Muturi defeated him during the party primaries.

Ita then defected to DP, the party after Muturi’s own heart (Muturi’s choice of KANU was purely to seek protection). Under these circumstances - and Muturi tells me this is in no way an excuse - Muturi says he found it difficult to de-campaign DP and Kibaki, and only went after Ita, which was an ineffective way to seek votes. But then Ita died in 1999, and Muturi won the by-election.

Once in the National Assembly, Muturi went straight to the ruling party’s backbench.

‘‘Coming to parliament was quite exciting,’’ Muturi recalls. ‘‘I met my role model Mwai Kibaki, who was leader of the Official Opposition, and the likes of Wamalwa Kijana, Paul Muite, Raila Odinga, George Anyona, and my good friend and neighbour Mukhisa Kituyi.’’ Clearly, Muturi’s heart was in the opposition seeing that all those he mentions were opposition MPs.

On the KANU side, Muturi made friends with Uhuru Kenyatta, who just like Muturi had had an unsuccessful run for MP in 1997. As Muturi got to parliament through a by-election, Kenyatta came in through a 2001 nomination, after which he was made a Cabinet Minister and later on picked as one of four KANU vice chairmen. Then in 2002, President Moi handpicked Kenyatta as his successor, a move which made Muturi opt to stay in KANU in 2002, out of his own volition.

‘‘My friend had been groomed and brought in as a presidential candidate,’’ Muturi says of Kenyatta. ‘‘I couldn’t leave him.’’

Choosing to stick with his friend was one thing, getting elected in Siakago was another. In Muturi’s recollection, the 2002 general election was a herculean task for him, considering the NARC wave was sweeping the Mount Kenya region, with Kibaki as the favorite. When the dust settled, only Muturi and Maoka Maore made it back to Parliament on a KANU ticket from their region. To Muturi, he and Maore survived because voters considered them on their merits and ignored the party on which they were seeking re-election. Muturi survived. Kenyatta lost, and the independence party KANU found itself in the unfamiliar territory of opposition politics.

It was around this time, Muturi aged 46 and Kenyatta 41, that the duo’s friendship grew even closer. With Kenyatta as leader of the Official Opposition, Muturi came in handy as Chief Whip, chaperoning KANU’s 64 elected and four nominated legislators, among other members of the opposition. Muturi’s and Kenyatta’s closeness and usefulness also materialized in Kenyatta chairing the Public Accounts Committee while Muturi was dispatched to chair the Public Investments Committee (PIC). In a sense, the dynamic duo were KANU’s parliamentary engine.

However, for Kenyatta, the opposition benches weren’t his natural habitat. And so as 2007 beckoned, KANU absconded its opposition role and endorsed President Mwai Kibaki for a second term. Unfortunately for Muturi, he lost the 2007 election, but still hanged out with Uhuru Kenyatta’s KANU crew, where he became organizing secretary in 2009. By this time, factionalism was taking root within KANU, with Uhuru Kenyatta being targeted for ouster since his action of endorsing Kibaki threatened KANU’s electoral survival in the long run. Once again, Muturi stuck with Kenyatta, a move which almost cost Muturi his ascendency to the helm of the Center for Multiparty Democracy (CMD), a non-partisan agency strengthening political parties.

It was while serving as chairman of CMD for three years that Muturi regrouped politically.

‘‘I worked very closely with the President, who was a Deputy Prime Minister at the time, at a place called the UK Center, which was located next to Parliament,’’ Muturi says. ‘‘We were together with people like David Murathe, and my role was to handle all legislative affairs.’’

The initials UK stood for Uhuru Kenyatta.

That is how Muturi was in the mix as Kenyatta set up The National Alliance (TNA) party, through which Muturi unsuccessfully sought reelection in 2013. Luckily for Muturi, his friend became president, and was leading the coalition with the highest number of MPs. Using his connections at CMD, Muturi managed to find resources to whisk away MPs from the President’s coalition to Naivasha, where his bid for Speaker was consolidated. Unlike in the previous constitution where MPs could run for Speaker, the Constitution of Kenya 2010 sought individuals who qualified to be an MP but were not an MP to be Speaker. Muturi fit the bill and had pretty solid connections.

This is how the once-upon-a-time hangout buddies came to lead two arms of government.

For Kenyatta, being president came with little room for error. On the other hand, for Muturi, coming to lead a National Assembly which had transitioned from a parliamentary to a presidential system of government allowed some leg room for mistakes. And so in the early days of his speakership, Muturi was perceived as an impatient and forceful umpire. When I ask him whether this was a fair assessment, the man owns up. It was all new and a little chaotic.

‘‘Previously, we used to have ministers and their assistants in the house,’’ Muturi reasons, ‘‘and I must say, in a way, that used to bring a level of decorum. Those houses had 222 MPs, but today we have 349 MPs under a totally new system with no local precedents. We had to borrow dork places like America, Brazil and the Philippines. And so you have 349 members from all manner of backgrounds, some shouting each other down, some shouting at you and asking you who you think you are, and so on.’’

Muturi says at this point, his only saving grace was that he had been a magistrate, and knew how to take charge of situations. Otherwise, he opines, things could have collapsed very fast, and he wasn’t the only one who was of this opinion. MPs who had served in previous houses were similarly awestriken by the state of affairs in the new set up.

‘‘There was no alternative other than being firm,’’ he says. ‘‘But things have since improved.’’

It was while listening to various needs from MPs and making interventions that Muturi had a light-bulb moment and realized he could ably lead Kenya. This is because to him, the biggest gap in Kenya’s governance was the lack of implementation, which prompted Muturi to establish the Committee of Implementation in Parliament, whose work is to follow-up on whatever the house passes and see if government meets its end of the bargain. A lot of times, and regrettably so, there are always more misses than hits, because a committee of the house can only push the Executive so much. To rectify this, Muturi is singing a chorus of order, discipline and integrity.

*

On the day I am to interview Muturi, veteran media man turned Muturi confidante David Makali tells me Muturi has a breakfast meeting at the Serena, and that it would be nice if my colleagues and I passed by and started our day with the Speaker. We arrive at the Serena expecting an intimate gathering, only to find Muturi has locked down two ballrooms at the hotel - Frangipani and Allamanda - and social-distance-ly packed them with 100 Nairobi County politicos.

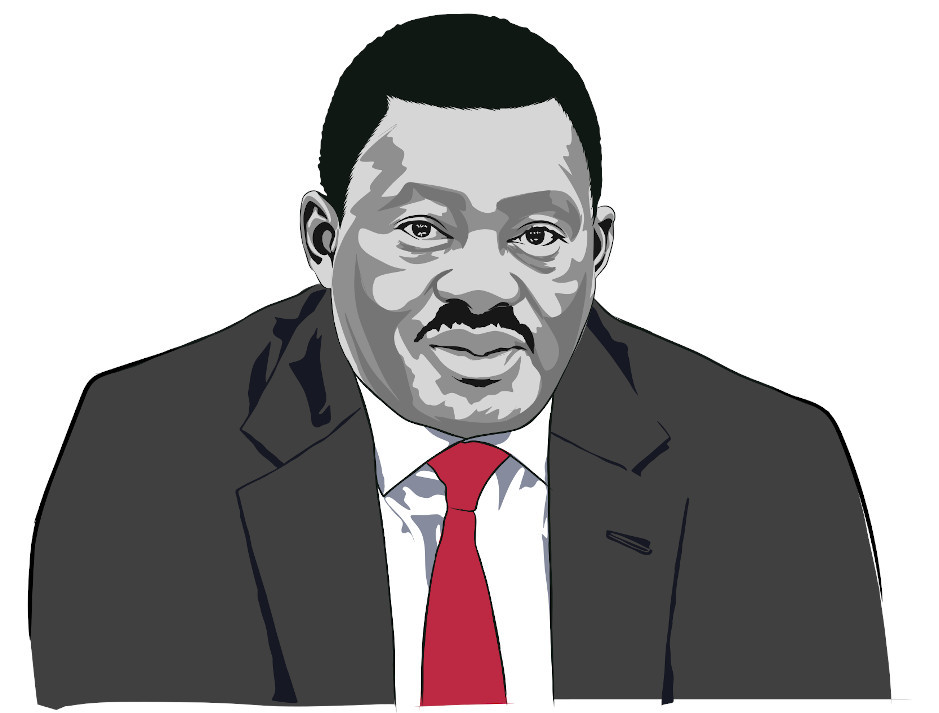

Until that moment, Muturi hadn’t explicitly pronounced that he is running for president, even after Gikuyu, Embu and Meru elders had taken turns subjecting him to mountain-climbing, hide-wearing and forest-isolating liturgies which culminated in his being crowned Spokesman of the Mount Kenya belt. Muturi considers the rituals sacred, and won’t delve into specifics. All he volunteers is that these were life-changing rites, which readied him for whatever eventuality.

‘‘You are being given a heavy responsibility,’’ Muturi says of the ceremonies he partook in, mostly in seclusion before the press got glimpses of the goings on, “and so you must think very hard, do some serious soul searching, before accepting what the elders are asking of you.’’

Muturi opens up that before the public witnessed his cultural coronation - happenings which caught the country by surprise considering no sitting Speaker has ever subjected themselves to such - elders from the larger Mount Kenya region had quietly approached him, one question in mind; What happens after President Uhuru Kenyatta’s final term comes to an end? At the time Muturi was approached by his interlocutors, the Building Bridges Initiative was running on full steam (and was soon running out of steam), and there were jitters that with President Kenyatta out of the picture, the people inhabiting the slopes of Mount Kenya may not have a mature, grounded and experienced individual to play all-politics-is-local poker with frontrunners from other regions of the country. Muturi was given three months to think about that question.

These were the precursors to the public events, first in Muturi’s backyard in Embu, after which the Embu elders delivered him to the Nchuri Ncheke shrine in Nchiru, Meru, who later on passed Muturi to the Gikuyu who did their thing at Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga in Muranga.

Muturi had answered the elders’ call, and the elders were satisfied. He was crowned Spokesman, with the elders reiterating that the role was apolitical.

However, a sea of campaign merchandise is floating at the Serena; from branded face masks to caps to polo shirts to life-size banners. ‘‘JB 2022’’. The uniformed ushers are all donning polos with the line ‘‘hatutaki soda, tunataka order!’’ In his own Machavelian way, the Speaker has appropriated order!, the terminology associated with his current vocation, and weaved it into his campaign lexicon. And now the operatives at the Serena were declaring - whether for optics or not - that they didn’t want Muturi’s handouts but were only interested in his bringing order!

The cultural facade had finally fallen off, and Muturi was now openly running for president.

After digging in on Muturi’s generous English breakfast buffet at the Serena, the group comprising former Councillors, sitting and former MCAs, former Mayors of Nairobi and a former MP psyche themselves up as they await Muturi’s arrival, the excitement so palpable as if they were meeting a sitting president. And when Muturi arrives, he turns tables on his guests in his typical poker-playing ways, and refuses to come across as the standoff-ish head-of-the-table kind of guy his no nonsense mannerisms on the Speaker’s throne make him look like, and opts to instead move from one table to the next, offering as many smiles and fist bumps.

Towering above them all, a purposely subdued-looking Muturi’s coup on the crowd works the magic - you could see in people’s eyes their astonishment at just how accessible Muturi had made himself, a far cry from his regal-looking life-size images projected across the room. Muturi should pay (again) whoever choreographed that man-of-the-people move for him.

To the uninitiated, Muturi could have been wasting money hosting that breakfast. But to those who know Nairobi, political gatekeeping is an entire industry, and one needs to speak to certain power brokers to procure access, especially of informal settlements. A story is told of how in 2017, President Uhuru Kenyatta had a preferred candidate for Nairobi Governor, but when the said individual attempted to hold a meeting in Dandora, his convoy was blocked miles away from the venue and his run for governor was stillborn out of that one incident. For Muturi, much as he kept telling me politics has no formula, he understood these sorts of protocols.

However, the biggest take-away from the Serena breakfast was that Muturi is purposefully avoiding critiquing President Uhuru Kenyatta directly for his administration’s failures. Rather, speaking in his way of saying without saying, Muturi laid blame on everyone else - svengalis surrounding the President and bureaucrats and apparatchiks working under Kenyatta - whom he blamed for subjecting the head of state to non-presidential chores of either having to shout himself hoarse repeating the same instructions over and over again like a broken record, or having to do supervisory roles in areas which should be competently handled by designated functionaries.

‘‘‘For me, the issues I am talking about are very dear to my heart,’’ Muturi tells me when we speak at his home, revisiting his Serena remarks earlier that morning. ‘‘The quality of service we give to our people is of concern to me. We have too many good ideas in this country. We talk about Vision 2030 and the Big Four Agenda, but why are we not achieving any of them?’’

To Muturi, Kenya’s public service is where the lethargy is at.

‘‘The entire public sector needs a rejig,’’ he says. ‘‘For me, if you’re unable to perform the job you’re given, then please take a walk. We have so many qualified young people. ’’

Muturi speaks with a firmness when he says these things, as if he could literally move from office to office enforcing. And yet he has to balance this with his admiration for Mwai Kibaki, who was a largely hands-off president. But maybe Muturi’s blessing, which is also his curse, is that he has watched from a vantage point as his friend has governed, and knows what’s possible and what isn’t. The curse is that he has to tread carefully as he seeks votes, not to paint his friend in bad light as an incompetent who couldn’t steady the ship. In fact, when I ask Muturi whether he’s had any conversations about his candidature with President Kenyatta, Muturi drops the matter like a hot potato. He adopts the ‘‘it wouldn’t be fair for me to go there,’’ but it’s clear Muturi is making his calculations, President Kenyatta is making his, and maybe they are both making certain calculations together, or not. It can be dicey, this friendship business.

*

After the Serena session, and after nearly everyone tries taking selfies with Muturi before he is whisked away to the waiting press, my colleagues and I are instructed to follow the Speaker’s motorcade to his home, where we are to have our sit down. There are only two instructions, first, ‘‘You have clearance,’’ and second, ‘‘Lose him in traffic at your own peril.’’ And so my colleagues and I pack up our cameras and line up right behind the Speaker’s convoy of three Mercedes Benzes, sleek S Class stretches. The whole chase-after-the-Speaker story has an you-shouldn’t-be-doing-this feel to it, but we need the interview, and we’d been given a brief.

Once Muturi is done speaking to journalists, he slides into the back left of his NA1-plated ride and off the sirens go. From Serena it is a quick rush into Nyerere Road, all the way up to the St. Paul’s Chapel junction, at which point the trail of Mercedes Benzes takes the wrong side of the road and speeds up to the University Way roundabout. An occupant of the lead car has a quick tete-a-tete with the traffic cop, before the vehicles are given the greenlight to take the wrong side of University Way. In a matter of seconds, they’re all rushing down Slip Road and into the Globe Cinema roundabout. From Globe it is up Kipande Road, followed by swift manoeuvres at the Ojijo Road roundabout, onto Taarifa Road, then Parklands Road speeding all the way up to the Sarit Center roundabout, where they take the third exit onto Ring Road Parklands, going up past The Oval, past Eldama Ravine Road, from where it’s a smooth ride up to the Speaker’s.

In our eagerness to not lose the Speaker, we have moments where we are driving too close to the chase car, so much so that it’s occupants beckon at us to take it easy. This entire time, as one of my colleagues sticks out his window holding a camera, I keep wondering if this is all a prank and we’re all about to get into some serious trouble. Eventually, we arrive at Thigiri.

Muturi’s residence is quite the spectacle.

At the bottom of his sloping compound sits a huge gazebo - bar, kitchen, indoor and outdoor dining areas, and a well landscaped garden rushing back up the hill to his house, with a covered pool. And yet Muturi seems unfazed, as if he’s just a passerby. We set up for the interview, have our long chat, and I have to stop with the questions because the Speaker is starting to show signs of exhaustion, much as he tells me he skips lunch on most occasions when working, a practice he perfected as a magistrate who wanted to avoid unnecessary adjournments when those appearing before him had traveled long distances to come dispense with a matter.

During the Serena event, I spot a conspicuous man dressed in a cut-to-fit pinstriped navy blue Kaunda suit, head clean shaven, donning dark eyeglasses and rarely speaking to anyone. He walks around a bit, no one asks him any questions. He looks like the sort of guy who would be running the show, but his sense of nonchalance makes one want to overlook him, yet you can’t.

Then it all becomes clear.

At the time we’re asked to trail Muturi’s motorcade, we get introduced to the guy, who had all along given me Mobutu-Sese-Seko-Kuku-Ngbendu-Wa-Za-Banga-swagger vibes, but it goes a notch higher when I see him standing next to an oldie but goldie red Mercedes Benz which is in a most pristine condition and whose engine, when it breathes, seems to have the firepower of a little nuclear warhead. When it raves, the ground seems to shake around it.

Sammy Njue Njiru. Muturi’s PA.

It is this man who I thought never talks who helps demystify Muturi for me.

In the early ‘90s, as Muturi worked as a magistrate in Machakos, Muturi was also serving as the chairman of the board of governors of a local school back in Siakago, a school which Sammy was attending. Whenever Muturi showed up with his Peugeot 504, Sammy and his schoolmates would always pose for photos next to the vehicle, aspiring to be like Muturi someday. It is from that setting, of Sammy looking up to Muturi, that the duo built a friendship spanning three decades, with Sammy volunteering to be Muturi’s personal driver in nearly all his campaigns.

It is Sammy who carries the memories of Muturi’s wins and losses, and shares with me his biggest heartbreak - him being by Muturi’s side while Muturi lost the 2007 elections, and receiving a call that his home in Eldoret (where he was working and had taken a two month leave to go campaign for Muturi) had been razed to the ground during the post-election violence. ‘‘My soul felt empty,’’ Sammy tells me. Both he and Muturi were out of work, but the friendship persisted, and now he treads carefully not to let their history interfere with work.

When we’re all done and dusted with the interview, Muturi invites my colleagues and I for lunch at his gazebo. He comes in after everyone has eaten and sits in a corner alone. After the Speaker is done with lunch, he has a quick word with Sammy, who then places a call to the motorcade which drives down the long sloping driveway to the bottom of the compound, turns around in formation and parks in front of the gazebo. Muturi says goodbye as he walks into the vehicle, dressed in one of his now familiar long sleeve navy blue Kaunda suits, as if matching with Sammy.

That moment of the Mercedes Benzes coming down the slope and Muturi taking the steps from the gazebo into the car and getting whisked away felt as if it was frozen in time, with Muturi moving as if no one else was present. Sammy turned to me, as we had our chit chat, and asked me - this coming after I had given him grief as to why he thought Muturi should be Kenya’s next president - and asked with all the sincerity he could muster, ‘‘Doesn’t he look presidential?’’

All I could offer was a grin.

Muturi had made his case. The Kenyan voter will decide.

At first, it was all harmless leisure.

Then it became an obsession when Muturi and his chums started

playing for money. Instead of

studying, the fellas played poker

almost nonstop, often till the wee

hours of the morning. The outcome of this unlikely school-night bustle was the group

either missing lessons as they

slept-in after long nights of

money-making, or simply skipping

classes altogether as they played

and made, and lost, and made, and lost dough.

At first, it was all harmless leisure.

Then it became an obsession when Muturi and his chums started

playing for money. Instead of

studying, the fellas played poker

almost nonstop, often till the wee

hours of the morning. The outcome of this unlikely school-night bustle was the group

either missing lessons as they

slept-in after long nights of

money-making, or simply skipping

classes altogether as they played

and made, and lost, and made, and lost dough.

It was possibly out of this change of

circumstance in the home front, and

the promise to stick to the straight

and narrow Muturi made to his father

before his departure, that the lanky

Muturi fully redirected his energies to

the basketball court, where as

captain he led Kangaru up to the

national championships. And

whenever he wasn’t throwing hoops,

Muturi moonlit as a table tennis

player, a sport in which he didn’t fare

badly either, representing Kangaru

provincially.

It was possibly out of this change of

circumstance in the home front, and

the promise to stick to the straight

and narrow Muturi made to his father

before his departure, that the lanky

Muturi fully redirected his energies to

the basketball court, where as

captain he led Kangaru up to the

national championships. And

whenever he wasn’t throwing hoops,

Muturi moonlit as a table tennis

player, a sport in which he didn’t fare

badly either, representing Kangaru

provincially.