Before January 1993, Moses Masika Wetangula had never met President Daniel arap Moi.

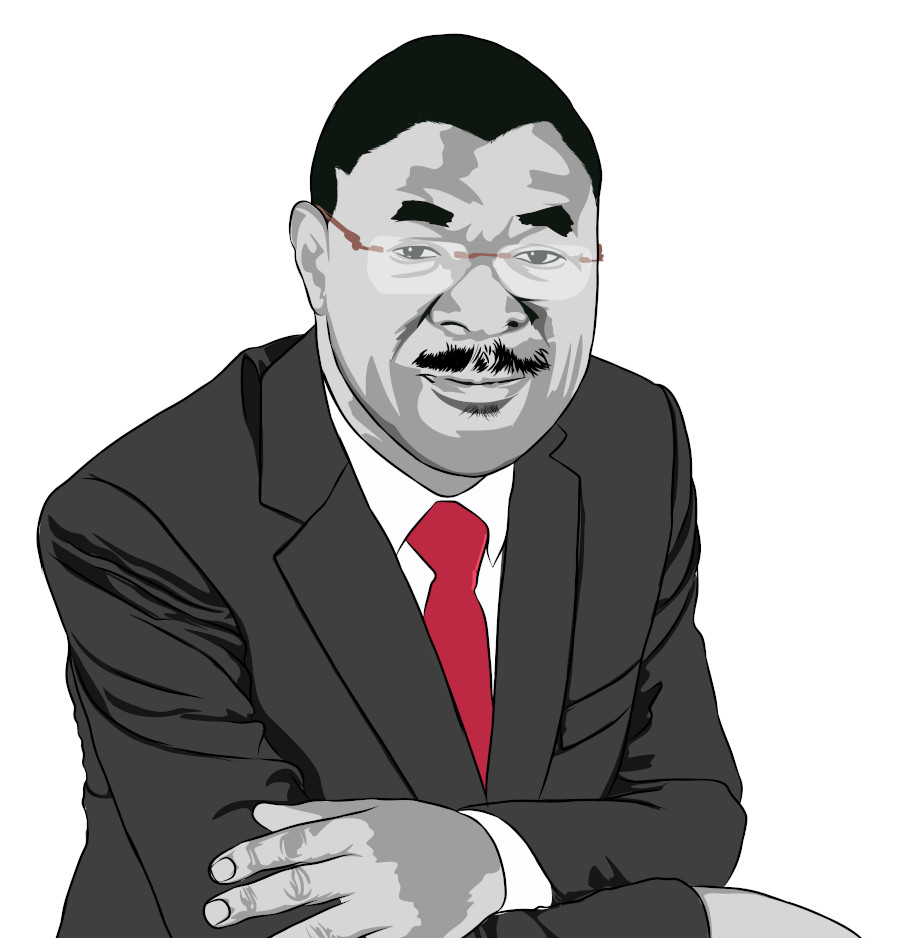

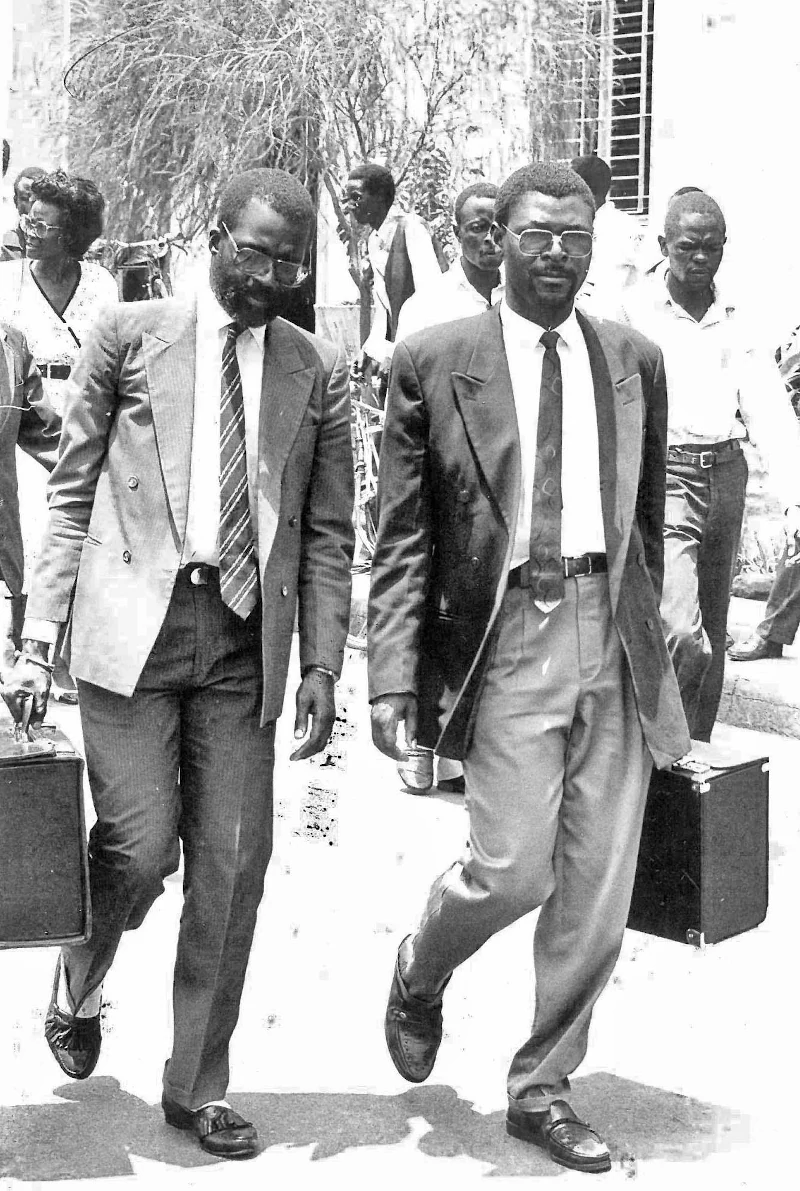

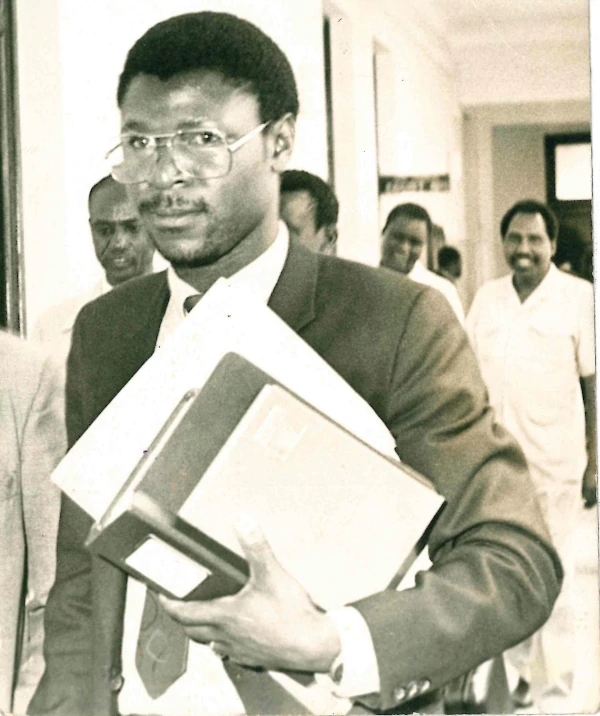

By this time, ten years after Wetangula represented the 1982 coup plotters, the man’s stature had grown in leaps and bounds. Wetangula and Company Advocates had since moved from Luthuli Avenue - in the midst of what Wetangula calls 24 hour disco noise, and crossed Moi Avenue, first settling at Hughes Building on Kenyatta Avenue, then to Queensway House on Mama Ngina Street, before taking tenancy at Corner House, a most prestigious address at the time located at the junction of Mama Ngina Street and Kimathi Street. The skyscraper had practices run by the likes of Mutula Kilonzo, who was the President’s lawyer, and Wetangula’s university classmate Fatuma Sichale, among a dozen other top law firms. Wetagula’s client portfolio had similarly fattened to include blue chip companies and state corporations.

At that juncture, according to Wetangula, running for office was the last thing on his mind.

But something else had happened.

In December 1991, Moi had capitulated and agreed to repeal Section 2(a) of the Constitution, allowing for multipartyism. It was the outcome of the subsequent 29 December 1992 general election - which Wetangula hadn’t participated in - that changed the course of Wetangula’s life.

‘‘A very vibrant, fearless and articulate team of young politicians were elected to Parliament,’’ Wetangula says and lists some of their names, ‘‘Paul Muite, Martha Karua, James Orengo, Anyang’ Nyong’o, Mukhisa Kituyi, Kiraitu Murungi, and many others.’’

This was good news for Kenya.

The bad news, especially for the ruling party KANU, was that these were all opposition MPs.

KANU and Moi had a headache, to which they found a solution.

‘‘I had always stuck to a routine of reporting to my office at 6am and never leaving before 7pm,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘And so one evening as I was seeing a client at 7pm, my then long serving secretary Jessica Olinga rushed in and told me there was somebody on the line called Moi.’’

Jessica: He says his name is Moi.

Wetangula: Go and tell him I am meeting a client. I will call him back.

Jessica: I will not talk to him. I think it is the President. You have to come and talk to him.

Wetangula went and picked the call. And true to Jessica’s word, it was President Moi.

Wetangula: Hello?

Moi: How are you Moses?

Wetangula: I am fine Your Excellency.

Moi: Congratulations!

Wetangula: What have I done Your Excellency?

Moi: You have been nominated to Parliament.

‘‘You have seen who has been elected,’’ Moi told Wetangula, referring to the formidable and troublesome opposition. ‘‘I want you to be part of the team that will help my party and my government. I have picked you because of your courage. Give me your best as your President.’’

Moi had one more request.

‘‘I want you to be part of the Speaker’s Panel,’’ he said, ‘‘to keep Parliament under control.’’

Being a member of the Speaker’s Panel was akin to being a temporary Deputy Speaker, meaning Moi was looking to commandeer the multiparty Parliament in whichever little ways he could.

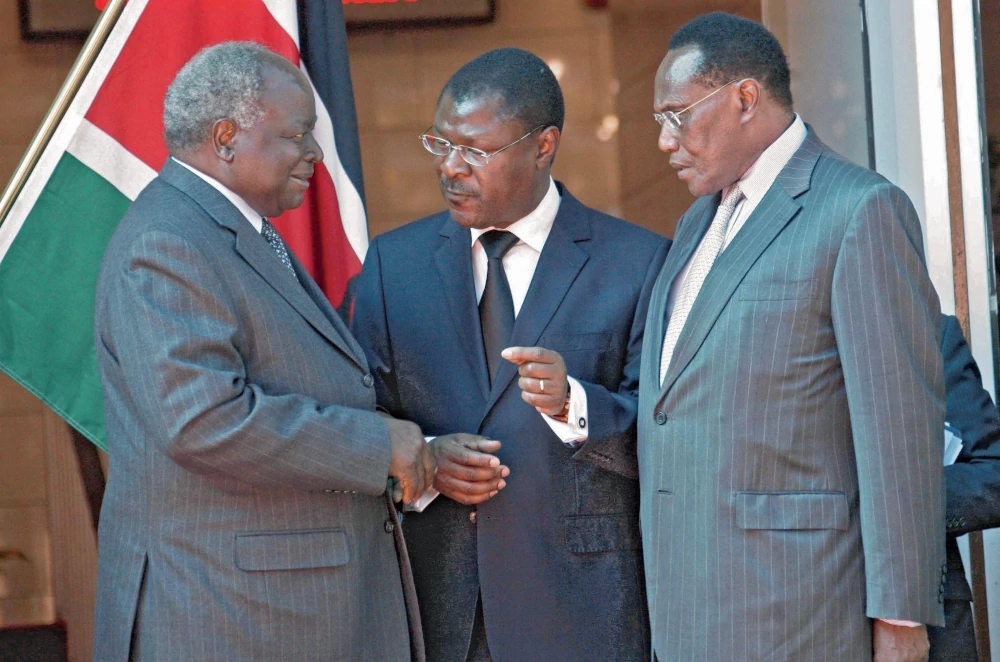

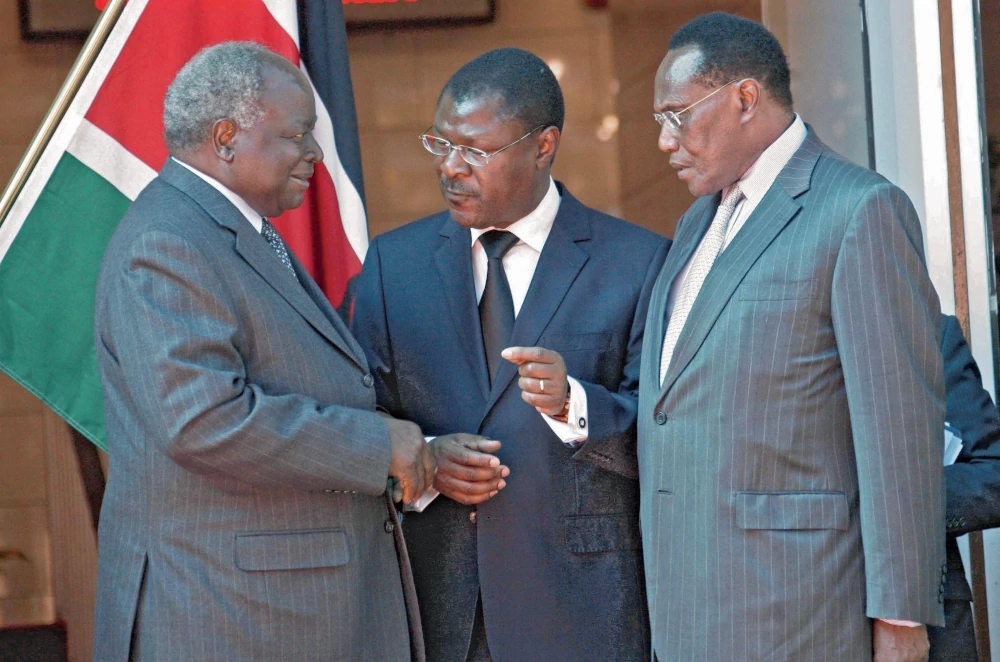

The following morning, Wetangula was invited to State House Nairobi alongside J.J. Kamotho and G.G. Kariuki, both of whom had lost elections and had been nominated. The other KANU nominees were Wilson Ndolo Ayah and Ziporrah Kittony. Also present were Elijah Mwangale - who had just lost to Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi, Attorney General Amos Wako, Vice President Prof. George Saitoti, Nicholas Biwott and State House Comptroller Franklin Bett, Wetangula’s contemporary.

From that point onwards, Wetangula became part and parcel of the KANU and Moi machinery.

But be that as it may, Wetangula, in his own admission, faced a daunting existential crisis.

Bungoma, the place where he came from, was solidly an opposition stronghold, with members of the Bukusu community having fallen in line to the last man in support of FORD Kenya, even after the death of their patriarch Pius Henry Masinde Muliro. Michael Kijana Wamalwa had been elected FORD Kenya’s second vice chairman in 1992, and became Muliro’s undisputed heir.

‘‘I had to find a way to delicately navigate between the interests of my friend Kijana Wamalwa, who was in the opposition but with whom we came from the same stock,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and those of President Moi, who had nominated me to Parliament.’’

This balancing act of trying to please Moi and not harm Wamalwa is what turned Wetangula’s nomination into a curse and a blessing; a blessing because it launched his political career, a curse since to his critics, working for Moi at a time when the entirety of Bungoma was against the man had elements of betrayal, a sort of blemish which Wetangula contends with to date.

‘‘After my handling of the 1982 cases, Wamalwa came to see me, curious about who I was,’’ Wetangula says of his private friendship with one of the opposition’s shining lights. ‘‘We built a friendship from that point onwards, and being avid readers, whenever either of us travelled abroad we brought each other books. And even when I was a KANU nominee, he’d come to my chambers and do his private calls and emails whenever he needed an escape from his office.’’

Wetangula was to pay a price for his 1992 choices during the 1997 general election.

Still keen on remaining useful to Moi, Wetangula threw in his lot with KANU when he sought the Sirisia Constituency parliamentary seat, at the time held by his teacher at Friends School Kamusinga, FORD Kenya’s John Munyasia. Munyasia’s superpower was that he was as gifted an orator as the rest of the FORD Kenya hotbloods, so that there was a joke that if one had beef with Munyasia, then the biggest mistake they could make was to allow Munyasia to open his mouth, because the moment he started speaking, you’d forget you were feuding with him.

Among the Bukusu, Masinde Muliro had built a tradition of asking the electorate not to merely elect representatives, but to instead elect warriors who would form part of his battalion at the national stage. To pass this message, Muliro would summon the triumphalist spirits of Bukusu warriors of yore, especially those who won the infamous Naitiri War, a cluster of fighters who were simply referred to as Naitirian. And so as he moved from one constituency to the next, Muliro would tell voters he only wanted them to elect leaders of the Naitirian calibre - nenya Naitirian, he would say, I only want Naitirian - and this would be code for the electorate to vote for whichever candidate Muliro endorsed. Michael Kijana Wamalwa inherited Muliro’s rule book.

And so as Wetangula campaigned in Sirisia on a KANU ticket, Kijana Wamalwa swept the rest of Bungoma and Trans Nzoia asking the electorate to only give him warriors of the Naitirian kind, all of whom had to be FORD Kenya candidates. The electorate listened and acted accordingly.

‘‘It was probably out of my friendship with Wamalwa that much as he went round campaigning for FORD Kenya candidates, he deliberately skipped coming to Sirisia to campaign for Munyasia, possibly in a bid to spare me the effects of his influence,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘There is no doubt that Munyasia felt shortchanged by Wamalwa’s act of tactically avoiding to campaign in Sirisia.’’

Even so, Wetangula still lost to Munyasia. The anti-Moi wave was impossible to mitigate.

After the electoral loss, Wetangula went to see Moi.

‘‘Young man,’’ Moi told Wetangula, ‘‘all politics is local. If you’d have sought my advice before running, I’d have encouraged you to go and join Wamalwa, run on FORD Kenya and win. If you’d have won, then I would have had a friend in the opposition, and I am sure when the chips are down you’d have stood with and by me.’’

It is a piece of advice Wetangula has never forgotten, and never hesitates to dish out.

And with that, Moi appointed Wetangula as the inaugural chairman of the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC), which has since become the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA), where he served for two and a half years before resigning to focus on Sirisia politics.

This time round, Wetangula implemented Moi’s advice religiously.

‘‘By the time we were getting to the 2002 general election,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘I was fully in Kijana Wamalwa’s fold, both as his personal lawyer and the party’s lawyer. I went for party nominations with Munyasia and defeated him, and had such an easy sail to Parliament.’’

Mwai Kibaki won the presidency, with Kijana Wamalwa as his Vice President.

As agreed upon during the pre-election phase, leaders of the conglomerate of political parties which had powered Kibaki’s ascension to the presidency submitted names of their preferred representatives in the Cabinet. Wetangula strongly believes Wamalwa submitted his name as part of the FORD Kenya list, but then Kibaki neither stuck to FORD Kenya’s nor did he adhere to the proposals given by the other coalition partners. Wetangula was left out.

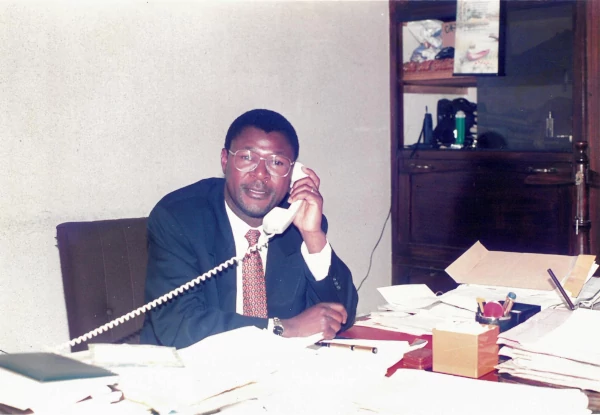

‘’In July 2003, a year after taking government,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘Mwai Kibaki called me and told me he wanted to appoint me as his assistant minister for Foreign Affairs. I accepted the offer. I believe it was Wamalwa who kept pressuring him to appoint me as originally intended.’’

Michael Kijana Wamalwa died two months later, at a time when Wetangula’s metamorphosis from KANU’s cockerel to FORD Kenya’s lion seemed complete.

When Masinde Muliro died in August 1992, the order of succession within FORD Kenya and by extension his Bukusu constituency was uncomplicated. Mukhisa Kituyi, who was a leading light in the party, conceded on grounds that he was young. Musikari Kombo, who was one of Muliro’s right hand men and a key financier, gave way to his senior. Michael Kijana Wamalwa stepped into the role with the full blessings of those who had coalesced around Muliro and FORD Kenya.

However, Wamalwa’s succession wasn’t as seamless.

Mukhisa Kituyi, Musikari Kombo and Noah Wekesa each wanted to lead the party. Wetangula, who was still making inroads within the FORD Kenya fraternity, supported Kombo with the promise that Kombo would hand over to him when the time was ripe. Kombo won the seat.

And yet, Musikari Kombo wasn’t Michael Kijana Wamalwa.

Where Wamalwa deployed charisma Kombo employed the slow motion counsel of the wise, and where Wamalwa was burning with ambition Kombo was handling Muliro’s legacy with velvet gloves, making it almost impossible for the party to roar. Soon, little uprisings fermented.

FORD Kenya’s currency had always been what Mukhisa Kituyi calls electricity - charged rhetoric delivered by a battery of hotheads coupled with an anti-establishment groundswell (unavoidable even if they were in government, like Wamalwa’s candid ‘I am afraid power has gotten into our heads’ speech delivered just before his demise). Kombo neither exhibited nor inspired any of these.

Seeing the electricity gap in FORD Kenya, Wetangula started plotting a takeover.

In the meantime, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wetangula deputized Kalonzo Musyoka, a man he had first met in 1985. At the time, a by-election had been occasioned in Kitui North Constituency, and 32 year old Musyoka was throwing his hat in the ring. As a show of solidarity, a group of young lawyers got together to fundraise for Musyoka. Wetangula was among them, giving a worthy contribution of 500 bob. Then quickly came Chirau Ali Makwere as Minister of Foreign Affairs, before he was replaced by Wetangula’s favourite, Raphael Tuju.

‘‘Tuju treated me very well,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He gave me the latitude to act as if I was the substantive Minister for Foreign Affairs by sending me to represent Kenya in all manner of very high profile ministerial engagements, which in turn gave me huge exposure in multilateralism.’’

Unfortunately for Tuju, he lost the 2007 elections.

And as Kenya was burning following the 2007 presidential election dispute, Kibaki had to call on Wetangula’s institutional memory at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In fact, as Kibaki’s re-election was faltering in mid-2007, Wetangula and others had positioned themselves by getting together and engineering a re-election vehicle, the Party of National Unity, whose constitution was drafted at the chambers of Wetangula and Company Advocates by a group of lawyers including George Nyamweya.

‘‘As the chaos erupted, President Kibaki called me and dispatched me to Addis Ababa to address the African Union, with the aim of convincing the outside world that Kenya was on its way back to stability,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘However, as I addressed the AU plenary and assured them that Kenya was salvaging the situation, all international TV stations started beaming images of Naivasha burning. It was almost impossible to convince anyone that all was well back home.’’

Raila Odinga had sent Anyang’ Nyong’o to address the AU and counter Wetangula’s claims. But according to Wetangula, he used his AU connections to block Nyong’o’s address. It was while in Addis - and possibly as a reward for his loyalty to the Kibaki regime - that Wetangula received a phone call informing him that Kibaki had appointed him Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Wetangula tells me he used his connections to block Nyong’o’s address.

While in Addis, Wetangula received a phone call.

Kibaki had named him Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Still in Addis, Wetangula met with Jean Ping, the then Chairperson of the AU Commission, and convinced him to come to Kenya and speak to the warring parties. Ping jetted into Nairobi and embarked on talks with the two groups. Wetangula then advised Kibaki on the urgency of an Africa-led mediation process, to which Kibaki and his consigliere Francis Muthaura agreed to.

Wetangula was up in the skies again.

‘‘I flew to Accra to meet President John Kufuor, who was the Chairperson of the AU,” Wetangula says. ‘‘I found Kufuor was away in his private home in Kumasi, from where he sent his presidential jet to come pick me up. It was a 90 minute flight. I met Kufuor, briefed him, then made a call to President Kibaki. The two spoke, then Kufuor and I addressed the international press at his residence. Kufuor agreed to come to Kenya the following day after he and I had agreed to rope in Koffi Annan. I had also suggested that we bring in a regional leader, and so I flew to Tanzania and persuaded President Benjamin Mkapa. Lastly, we agreed to bring onboard Mama Graca Machel.’’

This was the precursor to the Serena Talks.

From there onwards, Wetangula took his rightful place in the Kibaki government. I ask Wetangula, now that he’s worked with Moi and Kibaki, what were they like?

I ask Wetangula, now that he’s worked closely with Moi and Kibaki, what they were like.

‘‘Moi and Kibaki were complete opposites,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘Mzee Moi enjoyed talking to everybody. You could even say he enjoyed listening to gossip, because you could sit at a lunch table at State House and people who liked gossiping and maligning others would be having a field day -

Mzee unajua huyu, Mzee unajua yule, nini nini… - and he would listen to them. Sometimes he acted on whatever he heard, other times he didn’t. But he was very extroverted, and knew an individual by name in almost every village in Kenya.’’

It doesn’t stop there.

‘‘He liked going everywhere, he was not one to sit and let things happen,’’ Wetngula says of Moi. ‘‘He was hands on sometimes to the level of intrusion in the discretions of his appointees.’’

As if that wasn’t enough, Wetangula remembers that whenever one travelled with Moi - like that time Wetangula was invited to an official trip to Brussels - one was obligated to have a joint breakfast with him, a joint lunch with him and a joint dinner with him, as a delegation.

Kibaki was the reverse.

‘‘Mzee Kibaki is a person who kept to himself,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘As his assistant minister for four years and as his Minister for Foreign Affairs for another four years, I do not recall sharing a private meal with him, save for state banquets and post-cabinet lunches, where he rotated who sat next to him depending on who had issues which needed his attention.’’

And when the politics got heated, Wetangula remembers Kibaki calmly telling them that life was not about the people they liked but about the people they lived with, asking them to go find an amicable solution. And whenever ministers came to brief him, Kibaki listened and if he was satisfied, thanked them and let them go. Or if he had further queries or suggestions, Kibaki shared them then left the matters at that. There was no room for gossip.

‘‘And whenever we travelled out of the country for official State business,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘Kibaki stayed in his room, came out for meetings and retreated back to his room.’’

To his mind, Wetangula believes he represents the best of Moi and Kibaki.

‘‘And this makes me the better person,’’ he says.