Moses Sabstone Mudamba Mudavadi wasn’t just an accomplished educationist, strict disciplinarian and later on a powerful cabinet minister, but he was also a traditional African man who believed in raising his children a certain way. They had to find their own path in life and not ride on his name, and had to spend as much time in the village as possible, where for his political and social stature, Mudamba Madavadi was christened the King of Mululu. Wycliffe Musalia Mudavadi, his eldest son, lived to tell the tales.

‘‘From primary school,’’ Mudavadi says when we speak at his Musalia Mudavadi Center office, a souped up old bungalow located in a gated community at the tailend of Riverside Drive, ‘‘my father’s rule was that exactly two days after closing day, I was whisked away to Mululu on either Taifa Bus or Nairobi Bus Union, where I would stay until just two days before schools reopened, when I would make the trip back to Nairobi. This happened in first term, second term and third term without fail, until my university years. Over time, one gets used to the practice and starts seeing it as taking a much needed break from the city. You start looking forward to it.’’

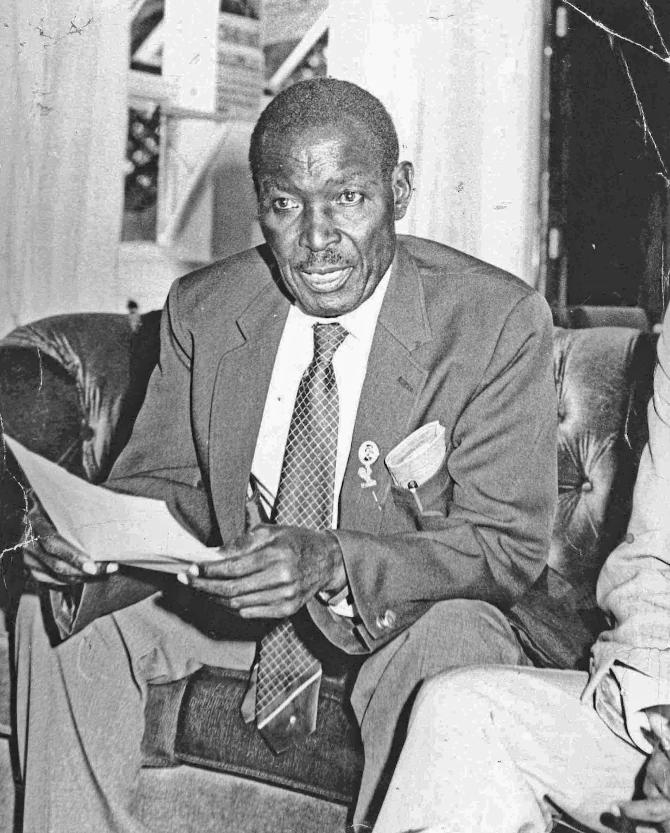

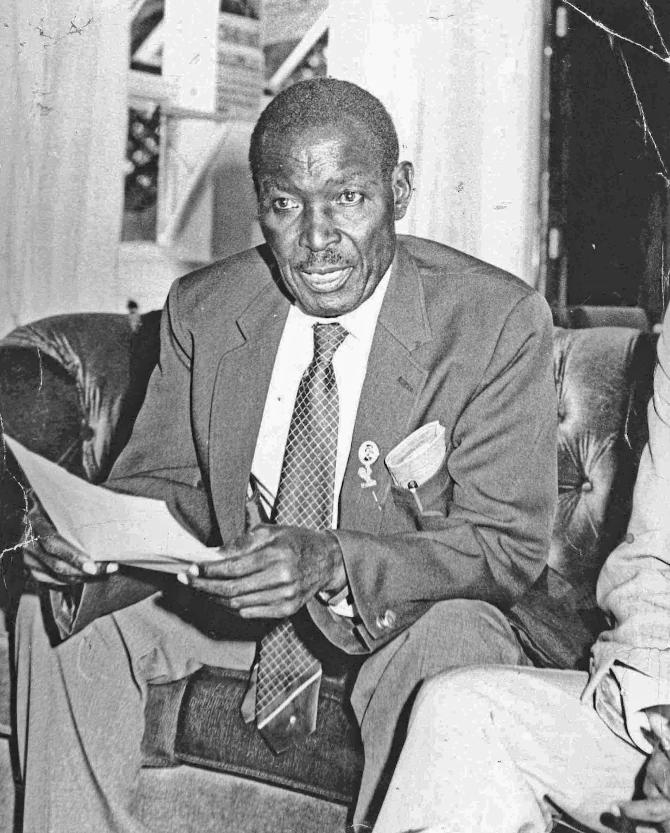

Moses Sabstone Mudamba Mudavadi

Moses Sabstone Mudamba Mudavadi

Mudavadi’s mother, Hannah, lived in Mululu, alongside her co-wife Rosebella. Between his two wives, Mudamba Mudavadi sired 13 children - seven with Hannah and six with Rosebella. Mudavadi was Hannah’s fifth born, a follower of four girls and followed by another two girls. I ask Mudavadi whether he was favoured being the only son in his mother’s house. ‘‘I was more like a minority,’’ he says and laughs. In the highly patriarchal traditional Luhya setup, it goes without saying that Mudavadi received extra attention, even if his folks didn’t show it openly.

‘‘Mothers have their own ways of parenting,’’ Mudavadi says when I ask him what influence his mother had on him. ‘‘Under her watchful eye, I got the opportunity to learn the language, since a lot of my childhood friends in the village did not attend urban schools and did not necessarily converse in English. I also learnt a lot of aspects of the culture, what is taboo, what isn’t taboo.’’

It is out of this Nairobi-boy-moonlighting-as-a-villager dynamic, coupled with Mudamba Mudavadi’s strong Quaker roots which insist on absolute humility and pacifism, that Mudavadi became grounded. ‘‘If someone didn’t know me personally,’’ Mudavadi says, ‘‘then they wouldn't guess who my father was because my father was a very different man. He made it clear to us that that (being minister) was his job and taught us to never invoke his name under any circumstances. His instruction was simple, follow the rules of the institution you’re in.’’

And so unfolded the life of a minister’s son minus concomitant privileges. By the time Musalia Mudavadi was of school going age, his father had been transferred to Nairobi from his Kabarnet station, which is where Mudavadi was born on 21 September 1960.

In Kabarnet, Mudamba Mudavadi - who was educated at Maseno School and Alliance High School before obtaining a diploma in education from Leeds University - worked as a District Education Officer in charge of Baringo, Koibatek, West Pokot and Elgeyo Marakwet. Once in Nairobi, five year old Mudavadi enrolled at Kileleshwa Nursery School, run by the Nairobi City Council (NCC). A year later in 1967, he joined Nairobi Primary School, yet another NCC institution.

‘‘In those younger days we were all day scholars, much as the school had a boarding facility,’’ Mudavadi says. ‘‘I doubled in all manner of sports - hockey, cricket, soccer and swimming, because much as these were public schools, the City Council had invested heavily in amenities.’’ After doing seven years at Nairobi Primary, otherwise known as Patch Primo, Mudavadi proceeded to the real Patch, Nairobi School, in 1974, where he did six years covering his O and A Levels.

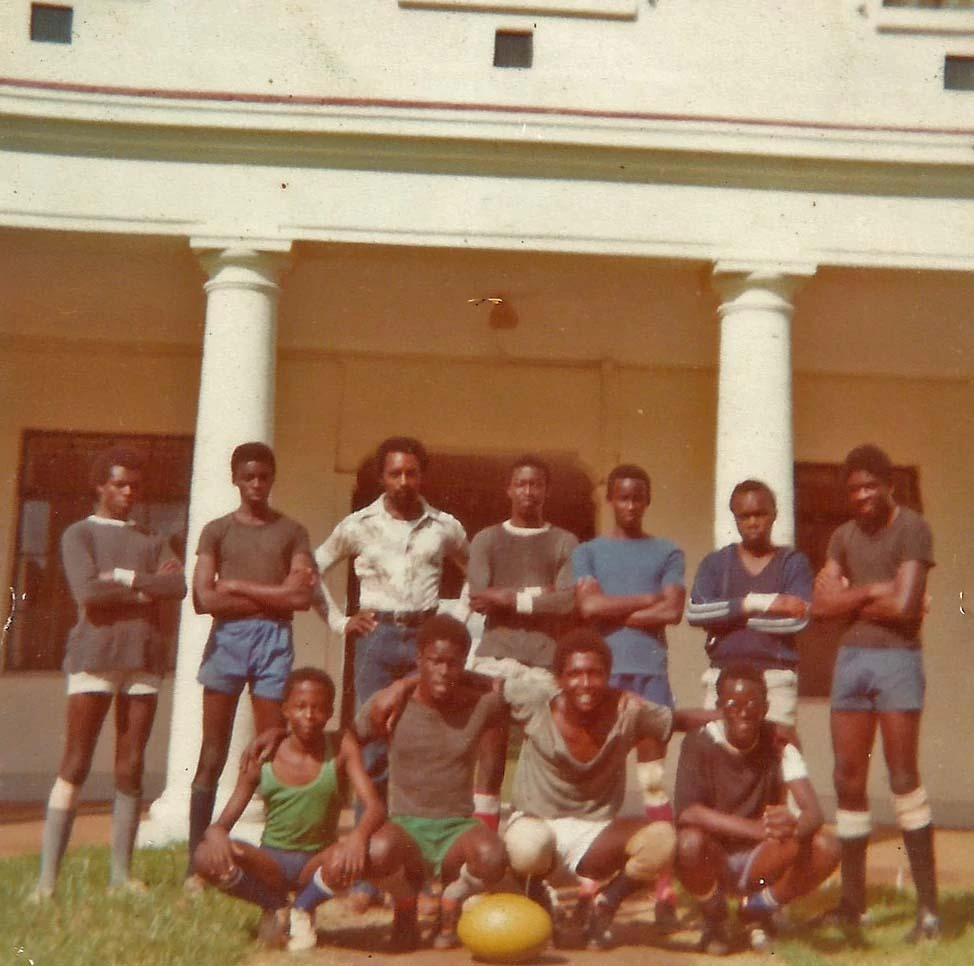

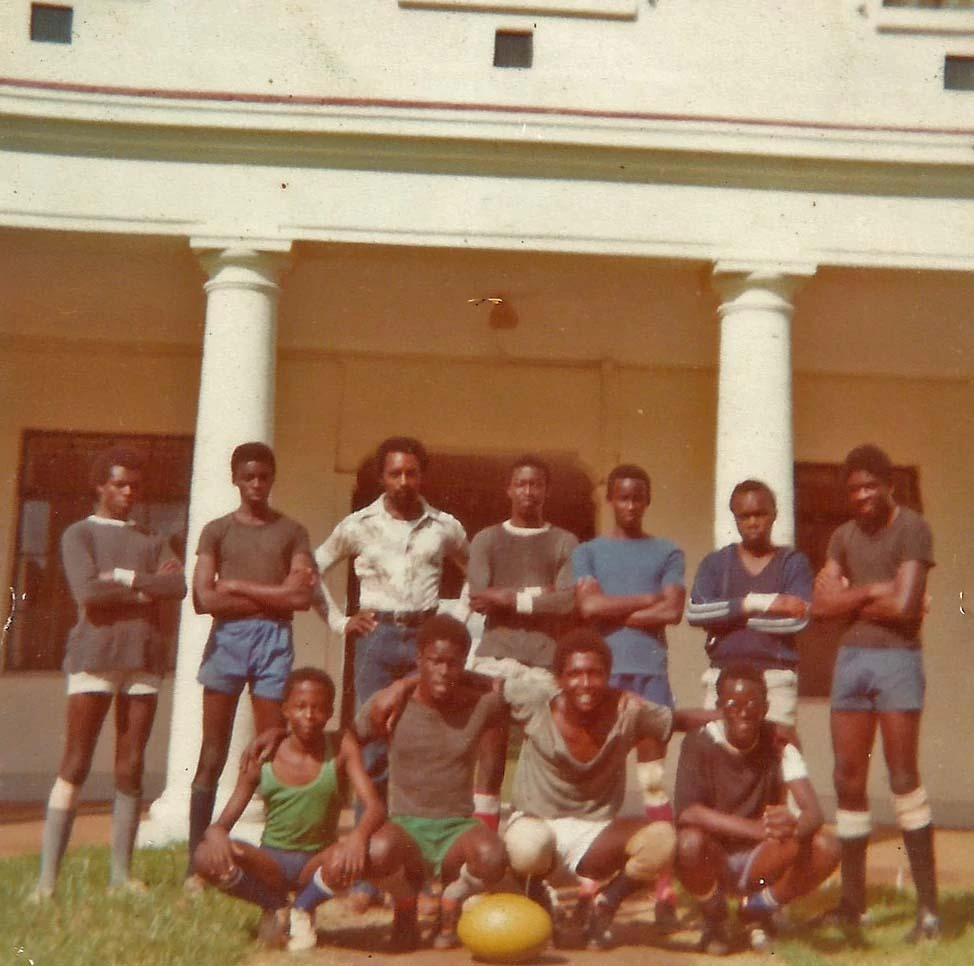

Musalia Mudavadi at Nairobi School

Musalia Mudavadi at Nairobi School

‘‘Those were very memorable six years of my life,’’ Mudavadi says. ‘‘I really enjoyed playing sports, going out on tours with the rugby team or to events at schools such as Limuru Girls, Alliance Girls, Moi Nairobi Girls, Kenya High and all the others. It was a moment when as young people we were being given an opportunity to have the world open to us, and I can say the foundation at Nairobi School taught me to be independent in thought and as a person. We learnt how to communicate, aspects of etiquette, and just how to be a proper well rounded individual.’’

Those school events, otherwise known as funkies, were intertwined with those communication lessons, since during interactions with girls schools, boys from Nairobi School weren’t expected to do one thing, to breeze, which was an inability to express oneself when mingling with their female counterparts. Further, considering that Mudavadi was a Head of House, what in other places was called a House Captain, it meant he over time became an enforcer of what it meant to be a Patcherian - always stay clean, always respect your seniors, never step on grass, never share a path with your seniors, always be punctual, and know the rules of the game even if you won’t play it. The game was rugby, a mini-religion at the school. Those had to be memorable six years.

While playing for Patch Machine, Nairobi School’s rugby side, Mudavadi was either a winger or back row - being one of three positions in the scrum, either the eighth man or one of the two flankers, positions which required one to not only be fast on their feet but swift and accurate with the ball. I take a look at Mudavadi’s full frame today and ask him whether he could entertain the idea of a rugby game, and his answer is a vehement no. ‘‘I wouldn’t dare,’’ he says, and laughs.

‘‘That’s where I got my nickname Phantom,’’ Mudavadi says, reminiscing about his Patch years, ‘‘because of how fast I was both on the pitch and on track, where I stood out in the 100 and 200 meter races. In rugby, speed is everything, and being fast played well to my advantage.’’

Looking at Mudavadi’s I-can’t-harm-a-fly-demeanor, I wonder how rough a player he was.

‘‘Rugby is a rough sport because you have to tackle someone hard, or someone will give you a bodycheck,’’ Mudavadi says, ‘‘and so we were trained and conditioned for it, because it is extremely physical. Once you’re on the pitch you have to bring it out, and be rough because the game asks for it, but once you’re off the pitch you don’t engage in any physical confrontation.’’

And what lesson did he pick from playing rugby?

‘‘Team work,’’ Mudavadi says. ‘‘You learn to coalesce together and be your brother’s keeper, because being a rough sport the only way for you to survive is to make sure you operate in a coordinated manner as a unit, otherwise you suffer serious individual and collective injuries.’’

Clearly, it was a hooligan’s sport played by gentlemen.

It was while Mudavadi was in form three at Nairobi School that his father was first elected MP for Vihiga in 1976. At the time, President Jomo Kenyatta was almost making his mortal exit, and there was a push by some Kenyatta insiders to change the constitution so as to block Vice President Daniel arap Moi from ascending to power were something to happen to Kenyatta, as it did in 1978. From his parliamentary debut until his death in 1989, Mudamba Mudavadi became one of Moi’s closest confidants if not the man with the final say, a brotherhood which had its roots in Kabarnet.

When Mudamba Mudavadi was working as a District Education Officer in Baringo, it so happened that one of the P4 teachers who was on his radar was a lanky Bible-wiedling fellow from Sacho, a young Moi, who Mudavadi recommended for further training at Kagumo Teachers Training College, so that Moi could be promoted to become a P3 teacher. After the training, Mudavadi recommended Moi’s to head Kabarnet Intermediate School, which was followed by a third recommendation, which changed Moi’s life.

During the 1955 Legislative Council (Legco) election, Baringo District Commissioner H.J. Simpson approached Mudamba Mudavadi asking him to run as Rift Valley’s representative. There were undertones that the incumbent, John ole Tameno, was having one drink too many. Being Luhya, Mudavadi declined the offer to stand in Kalenjin land, pointing Simpson to Moi’s direction. Moi too was hesitant, saying he was keen on keeping his teaching job. Mudavadi assured Moi that were he to lose the vote, he wouldn’t lose his slot as a teacher. Moi agreed, ran and won.

The Mudavadis and the Mois became family.

I ask Mudavadi whether his father becoming an MP changed his life in any way. ‘‘Not at all,’’ he says. This was around the time the old man read the riot act to his children, to never invoke his name anywhere. Mudavadi also shares that his father had lost two elections, in 1964 and 1969 - during which out-of-work phase he was employed by the Standard Chartered Bank - before he won the 1976 by-election, and so Mudamba Mudavadi didn’t want power to get into his offspring’s heads because he knew it was fleeting. Today you have it. Tomorrow you don’t. And when Kenyatta died in 1978 and Moi became president, Moi immediately appointed Mudamba Mudavadi minister. Again, Mudavadi says nothing much changed. His father stuck to his guns.

And indeed, nothing changed.

When Mudavadi was admitted to the University of Nairobi in 1980 to study for a three year Bachelor of Arts degree in Land Economics, he received his share of the student loan just like every other student, and stayed in the university’s halls of residence for the entire duration of his course. Still, holidays were reserved for that trip back to the village, and by public transport. But when the 1982 attempted coup unravelled, Mudavadi really wondered whether his father was not only a cabinet minister but a close friend to the President, because of what he had to endure.

‘‘Back then the University of Nairobi was the only university around, and so that was the place to be for anyone who made the cut,’’ Mudavadi says. ‘‘I am happy I joined the University of Nairobi because apart from enjoying the sporting and academic bits, I got to understand Kenya better through the people I met there. I’d have lost a lot if I had gone elsewhere for university.’’

At the University of Nairobi, Mudavadi carried on with his rugby playing ways, turning out for Mean Machine, the university’s revered rugby side which was simply referred to as Machine or Esichuma Absolutely - esichuma being Luhya for metal. Interestingly, Mean Machine had borrowed half of its name from Nairobi School’s Patch Machine, which Mudavadi had played for. It had been the case that Nairobi School and Lenana School commanded the high school rugby circuit back in the day, such that when players from the two rival schools met at the University of Nairobi, they dominated the rugby squad and reached a compromise, to borrow from Nairobi School’s Patch Machine and Lenana School’s Mean Maroon and name the university side Mean Machine. Mudavadi therefore played for two Machines; Patch and Mean Machine.

It was while Mudavadi was a final year at the university that the institution was closed as part of President Moi’s response to the attempted coup. All students were ordered to retreat back to their rural homes, from where they were to report to their local chiefs once a week. Mudamba Mudavadi, the minister, didn’t excuse his son. Worse still, when a swoop was done on suspected coup sympathizers by Moi’s secret police, the Special Branch, the dragnet caught Mudavadi.

“I was picked up from Mululu then taken to the cells in Kakamega, then subsequently the cells in Webuye, then Nakuru Railway Police Station and finally I was brought to Nairobi where I was taken to the General Service Unit headquarters,’’ Mudavadi says, ‘‘where I stayed for some weeks facing interrogation to see whether I was part of the coup plotters or not.’’

Among those arrested with Mudavadi whose fathers were either in business or public service were Kitutu Chache MP Richard Onyonka, Jubilee Party Vice Chairman David Murathe and lawyer Philip Murgor, while those picked up for being student leaders were the likes of Tito Adungosi, who died in prison, Mwandawiro Mghanga, Paddy Onyango and Oduor Ongwen. The father did not intervene. The son had to clear his name, without invoking the father’s.

‘‘I did not get too entangled in student politics,’’ Mudavadi says when I ask him why he thinks he was arrested. ‘‘Of course you would attend meetings convened by the student body from time to time, but I never took up any leadership roles. But that does not mean I wasn't political, because we had pretty political professors on campus, and the National Theatre was next door, where even though you’d be studying a science course or economics, you’d always find yourself going to listen to professors from the Literature Department, the likes of Micere Mugo and Ngugi wa Thiong’o, whose plays had political undertones. You wouldn’t want to miss them.’’

Mudavadi survived and rejoined the university after a year of its closure. Upon graduating, Mudavadi’s a-minister’s-but-not-a-minister’s-son’s reality kept manifesting. For starters, he started life living in a studio - that’s if you’re West of Uhuru Highway, or a bedsitter, if you’re East of Uhuru Highway.

After graduating in 1984, Mudavadi didn’t meet the expectations of someone of his family’s background, who’d either be shipped abroad for further studies or be gallivanting about town with one of those old model old-money-doesn’t-shout Mercedes Benzes or beat up but still in pristine-ish condition back-leaning Range Rovers. For Mudavadi, moving back home for a few months as he sought a job was the natural thing to do, because he was kinda broke. There was no more student loan or free meals at the student cafeteria.

Luckily for him, an interview at the National Housing Corporation (NHC) came back positive.

‘‘The NHC had houses in almost every major town in Kenya - Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Nakuru, you name it,’’ Mudavadi says. ‘‘And so part of my job entailed liaising with architects to develop new units, managing existing NHC rentals and selling off units which needed selling.’’

It was around this time that Mudavadi moved out to the studio along Ngong Road.

Besides being his father’s son, Mudavadi’s other claim to fame - which he equally didn’t exploit - was supposed to be that he’d spent three years turning out for Mean Machine, and earlier on Patch Machine, street credibility which counted for something within rugby circles. But as Mudavadi’s mates did the things rugby boys do and carried on playing club rugby, Mudavadi’s schedule at the NHC wouldn’t allow him to double in the game post-Mean Machine. And so he resigned himself to being one of the guys on the terraces, reminiscing about the good old days at Patch and Mean Machine. It was around this time that Mudavadi’s father looked at his eldest son with some leniency.

‘‘Possibly conceding that I had suffered enough,’’ Mudavadi says and laughs, ‘‘my father supported me in buying a Datsun 120Y, which cost about 70 thousand shillings back then.’’

After working for the NHC for about a year, in 1986 Mudavadi moved to the private sector after landing a job with Tysons Limited, where he did a lot of valuation of properties and assessment of investment in real estate. The salary at Tysons was much better, and so Mudavadi moved to a City Council house in Woodley Estate. It was around this time, as things were starting to look up for Mudavadi, that Mudamba Mudavadi rocked his son’s world.

“I had campaigned for my father during the 1988 general election, and he had recaptured his seat,” Mudavadi says with a pensiveness lingering in his eyes. “But then in February 1989, he suddenly passed on and I was asked to defend his seat during the April 1989 by-election.”

For the first time, the son could invoke the father’s name, posthumously.

Wycliffe Musalia Mudavadi was 28 years old.

In his wisdom, Mudamba Mudavadi may have thought him ripe for the next phase.

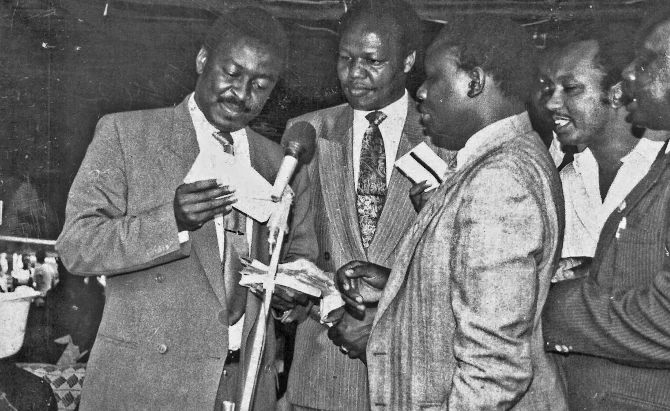

Minister For Supplies Musalia Mudavadi At A Harambee In Aic Church Kosirai June 1989

Minister For Supplies Musalia Mudavadi At A Harambee In Aic Church Kosirai June 1989

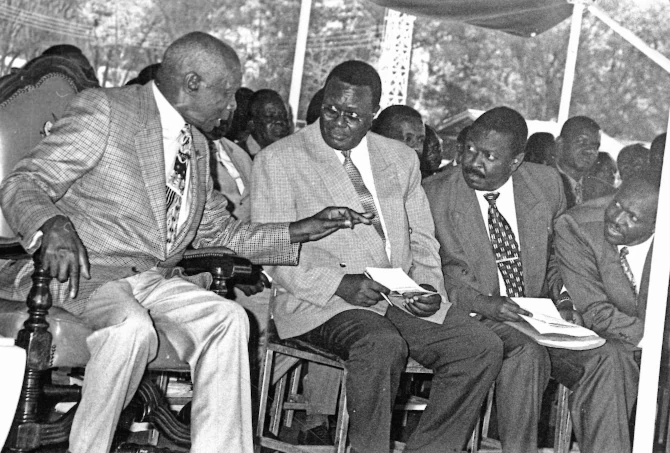

President Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, Chris Obure, Musalia Mudavadi and Kipkalya Kones

President Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, Chris Obure, Musalia Mudavadi and Kipkalya Kones

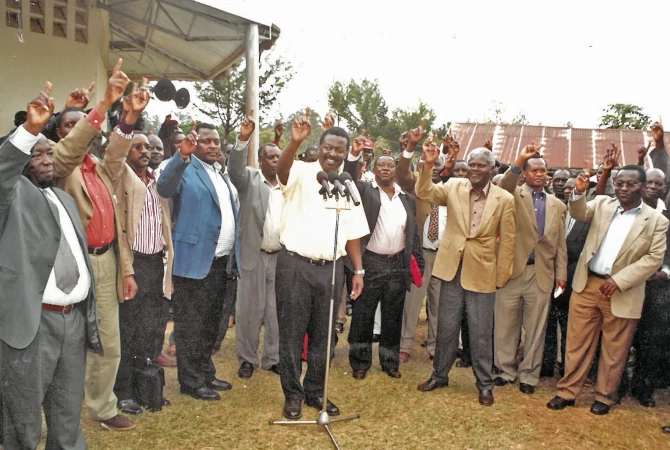

Vice President Musalia Mudavadi Addressing Kanu Supporters In Sabatia December 2002

Vice President Musalia Mudavadi Addressing Kanu Supporters In Sabatia December 2002

Musalia Mudavadi and Raila Odinga

Musalia Mudavadi and Raila Odinga