Kenyan vlogger Edgar Obare, popularly known as the ‘TeaMaster’ for the hot gossip he shares on his social media accounts, recently found himself on the receiving end of law enforcement after he shared travel visa details of Natalie Tewa, another vlogger.

His arrest on July 30 caused public debate on the increasingly common habit of sharing personal or private information online and whether it is justifiable.

This habit, referred to in popular parlance as doxing, involves searching for and publishing private or identifying information about a particular individual on the Internet, typically with malicious intent. This information might include a person’s phone number, home address, banking information, National ID card and travel documents.

Doxing has happened numerous times before to political and public figures across the globe. Even Michelle Obama, the former First Lady of the United States, has fallen prey to it. And as internet access grows in Kenya and other African countries, so is doxing.

However, the habit is proscribed under Kenyan law, as Data Privacy Practitioner Francis Monyango explains.

“We have the Right to Privacy under Article 31 of the Constitution, which includes the right not to have information relating to one’s family or private affairs unnecessarily required (by institutions or individuals) or revealed,” he says.

Article 33 further states that while the Constitution of Kenya guarantees the Freedom of Expression, that freedom does not extend to hate speech, and that means that, in the exercise of the right to freedom of expression, every person must respect the rights and reputation of others.

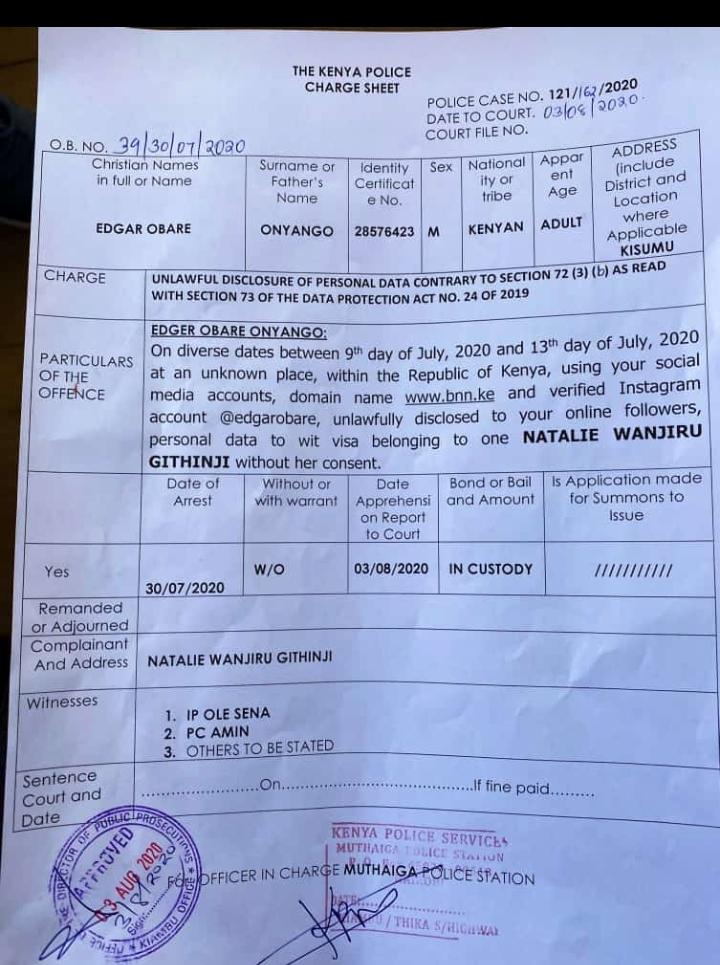

Kenya’s Data Protection Act, which has been in place since November 8, 2019, warns that a person who discloses personal data to a third party commits an offence. This is what Edgar Obare is being charged with, and his case marks the first charge under the Data Protection Act. He has pleaded not guilty to the offence after being arraigned in a Kiambu court.

Under the new law, the country is supposed to have a Data Commissioner, but that post has not been filled yet as the Labour Court suspended interviews for the position in July 2020 due to alleged illegalities with the recruitment process.

“I think we are at a very interesting point in terms of the jurisprudence of data protection law because we never expected that this Act will be used, especially for criminal law, but here we are,” Monyango says.

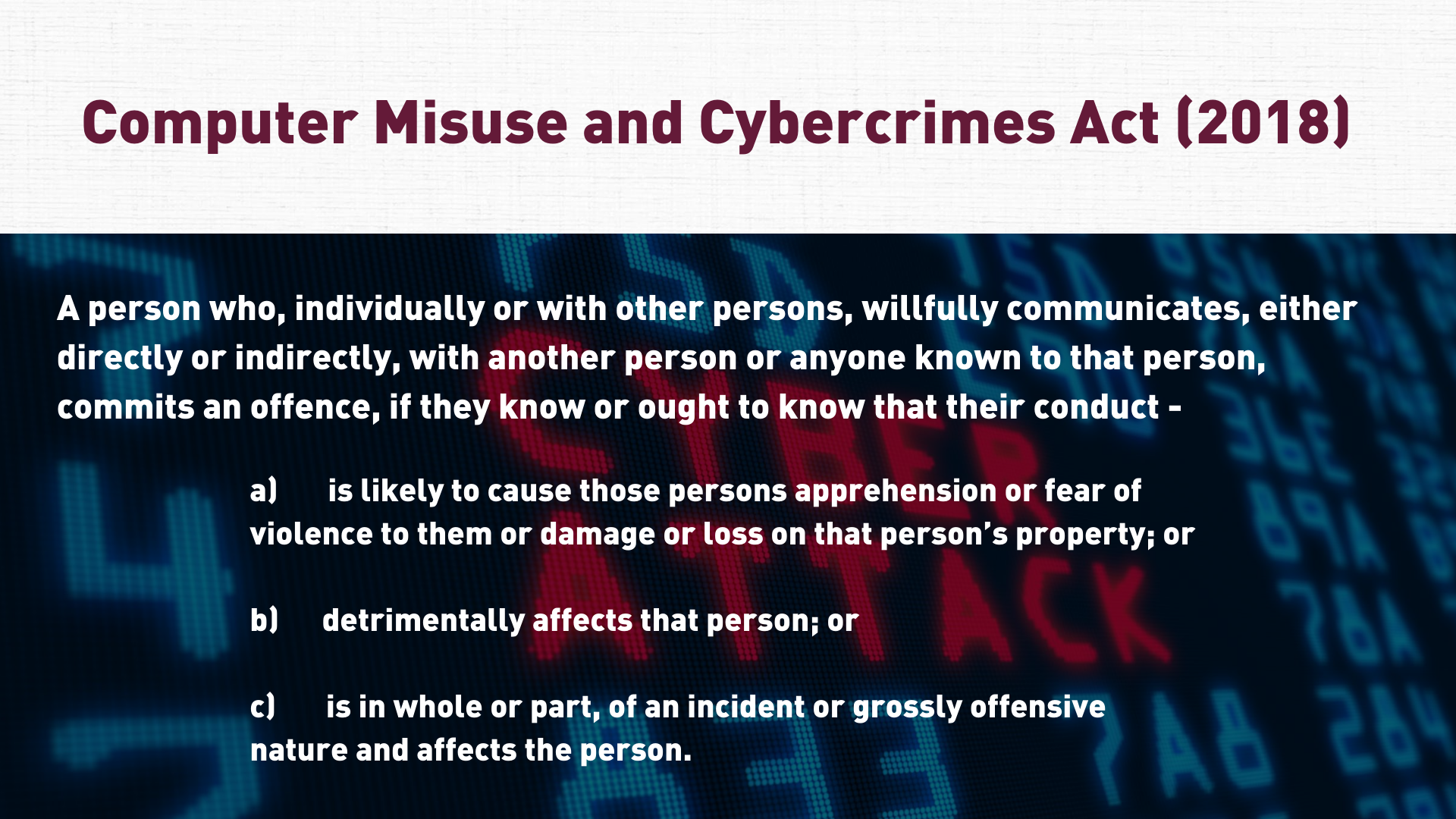

Citizens can also be charged under the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, which addresses cyber harassment.

A person who commits this offence is liable, on conviction, to a fine not exceeding twenty million shillings or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years, or to both.

While most African countries have no strong laws on cyber harassment, the African Union has drafted the Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data, which is a continental policy meant to guide its member states. It proposes that State parties should establish clear accountability in matters of cybersecurity at all levels of government by defining the roles and responsibilities in precise terms. Kenya and 46 other African nations have not ratified it.

Monyango observes that doxing or cyberharassment laws may not be as rampant in other African countries, especially where freedom of expression is limited. However, in jurisdictions where such freedoms are guaranteed, the habit is rampant.

One of the most memorable doxing incidents happened in Sudan when anti-government protests broke out in December 2018. Facebook groups run by women, which had primarily been used to dox potential suitors, were turned into revolution platforms where security agents and police officers caught brutalising demonstrators were doxed.

This made police officers hide their faces whenever they were out on the streets for fear of appearing in the groups. Sudanese citizens upped the social media uprising by subjecting errant police officers caught on video to Kangaroo courts, beating them up, or even chasing them out of town.