When I call Maina, my long serving cooking gas plug, the conversation is a little bit longer than our usual gas imeisha niletee mtungi ingine.

‘‘Bei ni ile ya kawaida ama mumepandisha?’’ I ask, word on the street being there has been a price hike on LPG. Maina takes the cue and runs with it, blurting out the prices for the various brands he stocks. The prices range between Ksh1300 and Ksh1500 for the 6kg cylinder and between Ksh3000 and Ksh3300 for the 13kg cylinder.

‘‘Si mtatumaliza,’’ I joke without joking.

‘‘Hata sisi tunaumia,’’ Maina says.

No one is safe in this economy.

Maina has been operating his Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG) retail shop since 2014. He is among the few stockists in my neighbourhood who offer a variety of brands to pick from and lets buyers trade-in cylinders from different LPG marketers, a not-so-common practice in the market.

This is despite the fact that in 2009, the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) under the Energy (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) Regulations of 2009 made it mandatory for businesses to be members of the LPG Cylinder Exchange pool and to accept or recognize the exchange of a cylinder belonging to another member when it came to consumers replenishing their LPG stock. However, this has been a slippery slope, considering many businesses only agree to exchange empty cylinders with filled ones of the same retail brand.

The Return of Makaa

Until now, it has been the case that Maina also offers free home delivery as an after-sale service, but he now tells me he has to suspend the practice due to the high cost of business.

After some quick calculus, Maina and I agree on the brand that I will pick and request him to send his delivery person to make the drop-off as they collect the empty cylinder. After parting with Ksh 3000 for the 13kg cylinder that was going for Ksh2500 a few months back, I am prompted to start thinking of ways to ensure the cooking gas will serve me longer. I would soon find out these weren’t kind thoughts but ideas in the minds of most Kenyans, who now punctuate their sentences with the now tell-tale familiar phrase, “in this economy”.

Maina works with select boda boda riders as opposed to having a permanent designated delivery person. So, when his appointed delivery person arrived at my house, I made the effort to engage him and get his thoughts on the new prices.– Mike, as he identified himself when he called me to get directions, tells me that he has a small meko (6kg gas cylinder) but with prices going up he does not know how he will survive.

‘‘Itabidi mama ametumia makaa lakini hata hio imepanda,” he says.

After the quick chat and him safely securing the empty cylinder off the back of his motorbike, I pay him the delivery fee and he rides off.

This was less than two months ago and now news has it that the prices could go even higher.

But why are we here?

Start Here…

For over a week, the Namanga One-Stop Border Post at the Kenya-Tanzania border was briefly converted into a parking lot for trucks transporting LPG destined for Kenya, Zambia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi . The unusual scene was born of a stalemate between the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) and a handful of LPG importers over tax compliance.

According to the importers stranded at the border, KRA slapped them with new levies, raising the the price of a tonne of gas from Ksh70,000 to Ksh108,000. KRA, through a press release, disputed the claims, asserting that the importers failed to give to Caesar that which belonged to him, in this case, the 16 percent VAT required on importation of the commodity. Instead, the importers have been undervaluing the imports and scamming KRA of its dues.

Kenya imports a bulk of its cooking gas from Tanzania, which is then trucked through the Namanga and Holili border posts. Tanzania has grown to be a favourite source of LPG in the East African Community because of the efficient offloading and storage infrastructure at its ports unlike the Mombasa port which has higher storage costs.

No Control

Disruptions at the Namanga border are expected to have a ripple effect on the supply and eventually the retail price of the commodity. Compliant traders are likely to capitalise on the supply hitches and hike prices while those who have to cough up the extra amount in tax plan to pass the cost to consumers.

Unlike super petrol, diesel and kerosene, the price of LPG is not regulated. The retail price of cooking gas is at the whims of importers, who often adjust the prices based on the forces of supply and demand. This has left the market exposed to exploitative and unscrupulous traders.

The government has been somewhat reluctant in whipping the sector into shape – as is the case with petrol, diesel and kerosene – arguing that setting price controls for the product will inhibit investment in the sector.

Putin’s War

Even though Kenya sources its gas from Tanzania and in some instances, the Middle East, rufflings in the international market always trickle down. A case in point is the ongoing invasion of Ukraine by Russia which has triggered disruption in the global energy supply. Sanctions imposed on Russia, a major supplier of oil and natural gas, have pushed the global prices of oil and natural gas to new highs.

The Good Old Days…

In June 2021, the government imposed 16 percent Value Added Tax (VAT) on all petroleum products including LPG. Before then, the 6kg cylinder was retailing at an average of Ksh900 while the 13kg cylinder was at Ksh1800. The price has now almost doubled. Presently, the price of the 13Kg cylinder retails for as high as Ksh 3500 at some retailers.

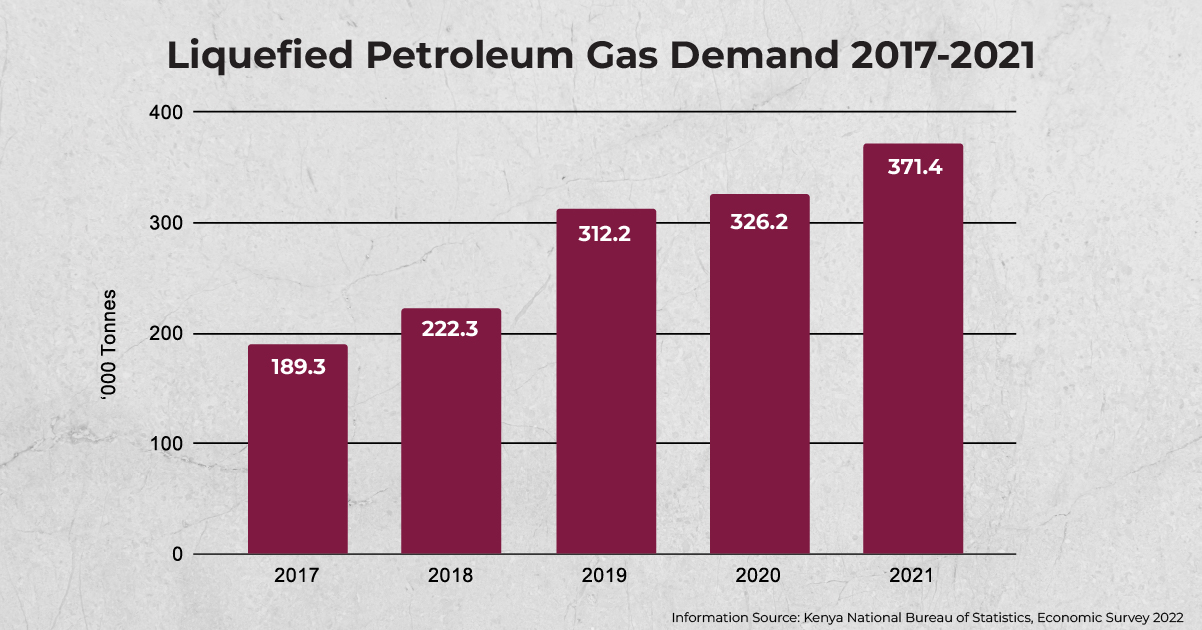

A graph representing the demand of liquefied petroleum gas between 2017 and 2021.

Previously, the highest recorded price of cooking gas was Ksh 3200 for a 13kg cylinder back in December 2011. At the time, the high costs of gas were driven up by the high cost of petroleum products in the global market.

Ogopa Makaa

While Mike and a multitude of Kenyans are now being pushed to alternative energy sources, the grass is not greener on the other side. Charcoal has remained out of reach for many Kenyans since the 2018 government ban on logging. A small 2kg tin of charcoal retails for about Ksh70 and Ksh100. Kerosene, on the other hand, is on the list of taxable fuel and is currently retailing at Ksh118.94 a litre.

But apart from cost, cooking with firewood, charcoal, and any other smoke-emitting household fuel is a health hazard as they are associated with major respiratory problems. The Kenya Household Cooking Sector Study published in 2019 revealed that these respiratory diseases kill about 21,000 Kenyans annually.

When the government zero rated LPG, the aim was to wean households off kerosene and charcoal, which are deemed dirty fuels due to the adverse effects on the environment. However, at the moment, the higher prices could erode the efforts made over the last decade in increasing the use of clean energy.

According to the 2019 Kenya Housing and Population Census, approximately 52.9 percent of households living in urban areas rely on LPG for cooking while those in rural areas account for 5.7 percent. The recent data from the Economic Survey 2022 shows that the demand for LPG rose further t0 371, 400 tonnes in 2021 compared to 189,300 tonnes in 2017 . The significant growth is greatly attributed to the zero-rating of LPG.

Light At The End Of The LPG Tunnel

For the longest time, Kenya has not had a state-owned common user storage facility sufficient to hold LPG and relies on privately owned facilities. The biggest import handling and storage terminal in Mombasa is owned by Africa Gas and Oil Ltd (AGOL) and has a 10,000 tonne LPG storage facility that handles more than 90 percent of imported LPG. The government-owned Shimanzi Oil Terminal has a 1,400-tonne capacity.

Plans have been in the offing to address the perennial inefficiencies that have characterised the petroleum products supply chain, including the upgraded Kipevu Oil Terminal. The government-owned facility is expected to handle four vessels of up to 100,000 metric tonnes of different oil products and an LPG line which is still in the works. The terminal is expected to store LPG imported by the National Oil Corporation of Kenya (NOCK).

In a draft proposal by the Ministry of Petroleum and Mining, NOCK is to be tasked with the duty of importing 30 percent of the petroleum products quota for diesel, super petrol, kerosene and cooking gas. According to the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA), this is meant to tame the market prices and ensure price stabilisation in the unchecked market.

In 2008, National Oil launched its SupaGas LPG brand, which was later complemented by a filling plant at its national terminal in Nairobi’s Industrial Area. The plan was for NOCK to avail in the market subsidised products and bring a semblance of balance.

To further subdue the burden of high prices, the government has also revived its subsidy scheme for affordable cooking gas, with a Ksh471 million allocation for the new financial year starting July.

Hopefully, with such mitigatory measures in place, Kenyan breadwinners will no longer dread the term gas imeisha as much as they currently do.