It was around 9pm when Demtila Gwala – Tila, for short – turned on a flashlight to see her patient clearly. Tila had just received a distress call from a resident of Kiamaiko, an informal settlement within Mathare. The patient, a woman in labor, was now screaming in stark terror. She was Tila’s former classmate, with whom she grew up with. Now, only a few days into her newfound job of providing life-saving health services to a population that needs it most, Tila had to come to the aid of her childhood friend, who by this time was soaking in blood. With no experience in maternal care, Tila was flustered.

Tila made two phone calls in succession. The first was for an ambulance, to ferry the patient to Mama Lucy Hospital, the nearest functional facility located 45 minutes away. The second call was to her mother, to come help midwife the birth seeing that they were time-barred. Securing the emergency vehicle, as always, was a rather elusive task. Most ambulances are almost always preoccupied with other emergency missions. It was therefore not surprising that after struggling to navigate Mathare’s rugged terrain, the ambulance arrived an hour later, by which time the baby had been delivered and Tila had cleaned the room. With the assistance of concerned neighbors, Tila and her mum carried the new mother out of the house. She would now be under better care in the ambulance. Unfortunately, the baby did not make it.

First line of defense

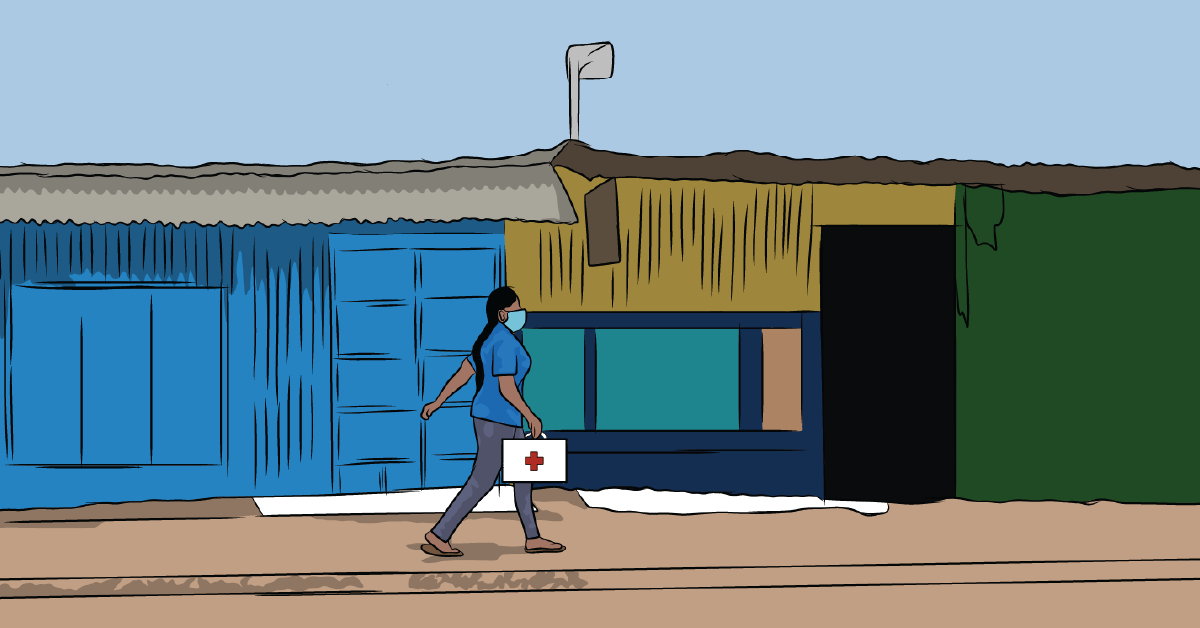

Five years later, Tila is still a Community Health Volunteer (CHV) in Mathare. Since her baptism of fire half a decade earlier during the childbirth incident, Tila wakes up every day, driven by the belief that every mother and child deserve quality healthcare – whatever quality means in a setup like Mathare.

“I do my bit by guiding those households assigned to me on personal hygiene and sanitation, as well as educating them on the dangers of defaulting medication,” Tila told me as we entered a narrow, dark alley that led straight to the doorstep of a single room iron-sheet house. Tila was here to observe Lydia, a 21-year-old living with Autism.

The average day of a CHV in Mathare begins at dawn with a series of such visits. Each volunteer is assigned an average of a hundred households, where they frequent to ensure patients have access to vital healthcare supplies such as medicine, condoms and bed-nets. The CHV’s also accompany patients to health facilities for check-ups. Thereafter, CHV’s draft monthly reports to the Community Health Assistant (CHA), who then reports to the County Health Department, detailing how many households were visited and the number and nature of cases referred.

Everyday heroes

A mother of two, 32-year-old Tila has become a well-known face and community leader across Mathare. Apart from being a key player in campaigns against Malaria, HIV, Measles, Polio and Gender-Based Violence, Tila’s warmth and exquisite social skills always make her the center of attention, something she had gotten accustomed to way before she became a CHV. Her endeavors in changing the circumstances in Mathare have since earned her the byname Chairlady, a name I hear many residents use to teasingly refer to her as I accompany her from her home visits to the CHV’s meeting place in midmorning.

“The community has chosen us to work for them,” Tila told me. “They listen to us. They know us. They understand us. They trust us. Here, we feel seen, even needed.”

Covid-19 in Mathare

It has been more than a year since this massively crowded Mathare area was faced with one of its biggest challenges – social distancing – to rein in the rampaging Coronavirus pandemic. As pandemic fatigue sets in, a majority of Kenyans have relaxed their guard and started moving on. But such is not the case for some 15 men and women assembled at a dim-lit church hall, and who, out of sheer duty, were called upon during the height of the crisis last year.

The 15 in attendance were only a fraction of the total 50 CHVs in Kiamaiko. The World Health Organization estimates that there are over 1.3 million community health workers worldwide, whose work includes gathering data, analyzing and sharing information on health issues with communities, health professionals and governments. According to the WHO, these health workers are understood as those with shorter training than professional health workers, supported by the health system but not necessarily as a part of its structures.

Tila and her group are among about ninety thousand CHVs, who the government heavily depends on for contact tracing, conducting surveys and collecting data to help in fighting Covid-19, a virus that has influenced a decline in hospital visits across the globe either due to shortage of bed facilities or due to fears of contracting the disease by patients suffering for unrelated ailments. By connecting patients with not only resources, but also social support and a sense of community, CHVs remind us of how narrowly we have defined health within a clinical setting.

Lack of support

But exactly how supported are they? I seemed to unsettle the meeting with my somewhat uninformed question. The obvious answer dangled on everybody’s lips. It was then when I established that each CHV lot, before they are deployed, undergoes training for about three weeks and in the case of epidemics such as Covid-19, at least ten days.

However, disturbing was the fact that government continues to overlook the safety of the volunteers as they are barely resourced with any protective gear.

“At the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic,” one CHV explained, “We only received five litres of hand sanitizer for every ten CHVs – half a litre for each of us, which was remarkably insufficient to keep us safe in our line of work, and to protect our families at home.”

“The government has only very recently given us masks since the pandemic began,” another CHV clarified, just before her colleague seconded, “only fourteen pieces for each of us!”

Globally, medics have been lauded for their efforts in the fight against Coronavirus. But this group of people remains unheard. Their efforts in containing Covid-19 remain underappreciated, and neither is attention given to the multiple challenges they encounter in their line of duty every single day.

Granted, CHV’s may not be many in number, but in underserved communities such as Mathare and other informal and rural settlements, their life-saving impact is monumental, almost unquantifiable. These, coupled with the complexities of unpaid work bring in efforts of one finding ways of supporting their families financially – Tila sells men’s clothing as a side hustle to earn an income to sustain her family – that CHV’s hope the government can urgently put them on its payroll.

“Despite our fierce dedication, we are barely getting by – mostly desperate,’’ Tila observes. ‘‘We are forced to work numerous casual jobs to stay afloat.”

The Budgetary Gaps

In the 2021-2022 Finance Bill, the Kenya government allocated KES 121.1 billion to the healthcare sector, with 14.3 billion going towards procurement of Covid-19 vaccines while 1.2 billion being set aside for the recruitment of health workers under the Economic Stimulus Programme, among other key allocations.

As it stands, Kenya has a chronic shortage of health workers. While the WHO recommends 45 physicians, nurses and midwives per 10,000 people, Kenya has 13 health professionals catering for every 10,000 people. This is because about 40% of graduating medical students go to other countries in pursuit of greener pastures every year, owing to the lack of growth opportunities at home. So Community Health Workers are a very relevant populace in this context.

Yet, as I learned during the CHV meeting, community health workers are a largely disgruntled lot. Their role is silently overlooked as inconsequential to the healthcare ecosystem, fueled by the misunderstanding that the community level in the healthcare infrastructure is negligible. This is further reflected in the fact that CHVs work as volunteers, meaning they are barely paid. One man in the meeting, Seth Owino, says the government stands no chance to meet its Universal Health Coverage targets without having Community Health Volunteers as paid within the health workforce framework.

“While envisioning the UHC, the Jubilee Government puts the cart before the horse in assuming that when you visit the hospital, you will get services there. History has taught us that that is not the case,” Owino told me. “UHC should not be founded on a spirit of sending people to the hospital, but rather improving the health of the people.”

Owino, Demtila and their counterparts are a totem of true kingpins of health services in communities that have been systematically denied healthcare. They are the formidable force at the heart of eliminating healthcare disparities, to increase wellness and social justice.

Perpetual front-liners

For the most part, Kenya is phasing out of a grim national nightmare.

Children are back in school, crowding matatu stages in their uniforms as they head home in the evening. Sports are back, church pews and political gatherings have filled up again, with people trading rowdy hugs during the cheering, a glaring change from the social distancing which rules humanity.

Yet the CHVs aren’t catching a break.

“We can never give up. We must not. All our efforts come from the heart,” Owino said. “When I became a CHV, I had no clue what I was getting into. I like to think of it as a calling because one never really stops caring. You give up today, then if you are called upon for assistance tomorrow, you immediately forget it all and run to the rescue of your patient.”

Owino and the other CHVs draw their motivation from seeing patients they took to hospital as critical, recuperate. It becomes an acknowledgment of sorts, even if their work receives no other validation. The Nairobi County Government has over time promised CHVs a stipend, a promise which has never materialized. But CHVs aren’t giving up hope. Soon, their weekly brief was over. With their agenda set, the gathering exited the church, like troops heading out for battle.