Today, communities across the world are marking International Safe and Legal Abortion Day, a day which draws its origins in the Latin America struggles of the ‘90s in pursuit of the decriminalisation of abortion.

And so as the world marks this important day—either a celebration of a win for human rights and dignity for societies with access to safe and constitutionally legal termination of pregnancy, or a reminder to keep up the clamour for countries which are yet to enact such legal provisions—one cannot help but think of the critical yet often overlooked issue of abortion rights in Kenya, what may be referred to as “termination of pregnancy.”

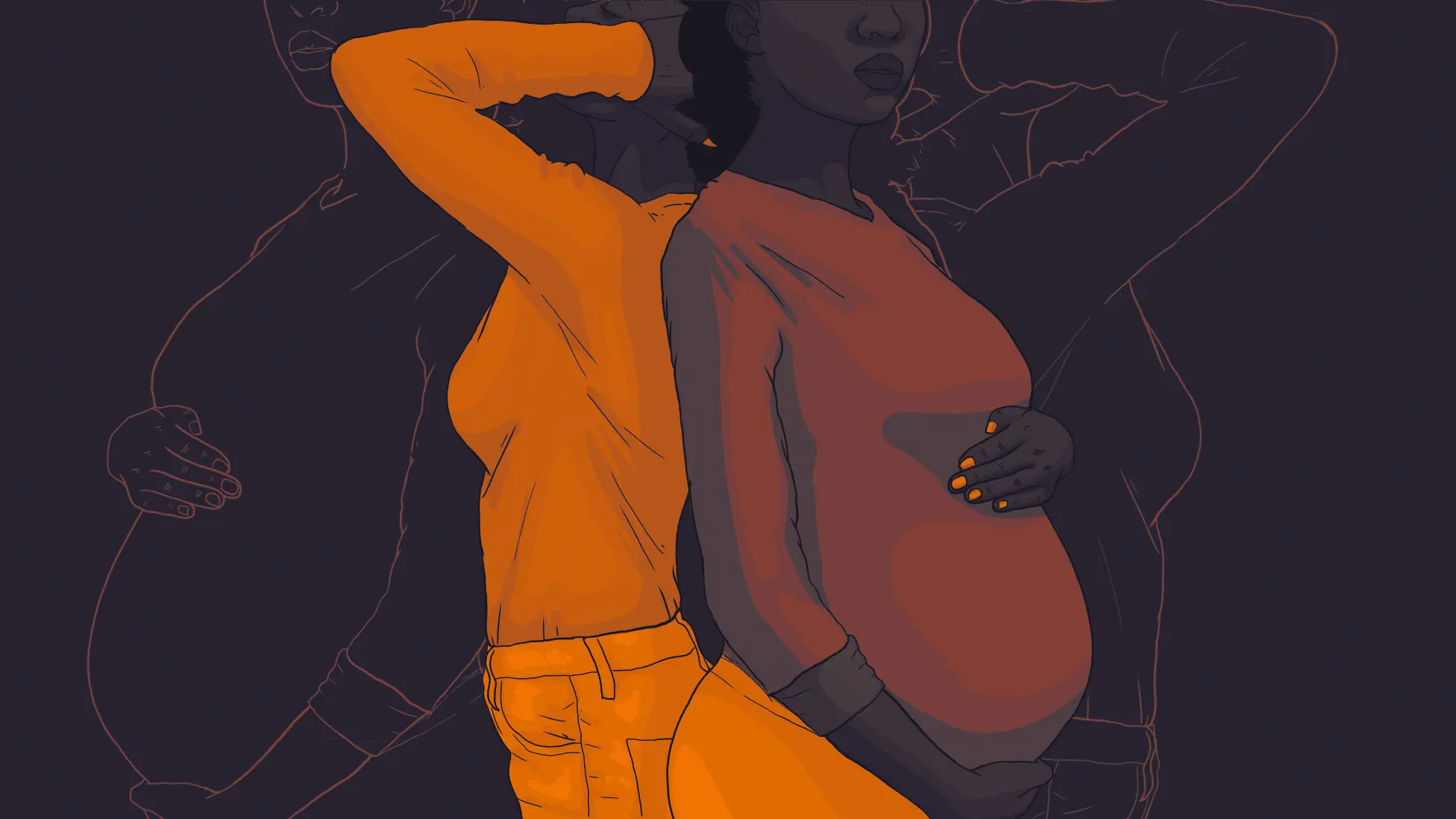

For starters, it is important to appreciate that termination of pregnancy is not merely a medical procedure (that some may even consider a luxury, sadly), but rather an indispensable component of comprehensive healthcare for women, who form at least half of our country’s population. It is therefore tragic, to say the least, that such a crucial component of a woman’s well-being remains inaccessible to the majority of Kenyan women, largely due to legal restrictions and the non-realisation of existing legal rights and provisions under our Constitution.

Take the tragic case of May*, a married loving mother of four, described as the bedrock of her family living in Nairobi County. She personified the enduring spirit of countless Kenyan working class women—working one or more jobs to contribute to the family income, raising four children, while still being an active community member. May broke her back alongside her husband trying to fend for her family during these extremely difficult economic times. She couldn’t afford one more child. So when May and her husband Job* got pregnant with their fifth child, things took a turn for the worst.

May and Job’s nightmare was exacerbated by the fact that Kenya has a prohibitive legal climate that makes it difficult for Kenyans to access the services of qualified medical personnel. These conditions forced May and her husband to opt for a backstreet abortion. Because Kenya fails to provide women with access to lifesaving reproductive healthcare, May paid the ultimate price: her life.

Seven Kenyan women die from unsafe abortions every day

The financial toll of unsafe abortions on Kenya’s healthcare system is staggering. According to the African Population and Health Research Center, as of 2016, it costs Kenya over 533 million Kenya shillings annually to treat complications from unsafe abortions. The personal financial cost is even more daunting. A safe, clinical termination of pregnancy can exceed KSh 20,000—a prohibitive sum for most Kenyan women. This economic hurdle drives many women into the perilous corridors of unsafe abortion providers, resulting in a reality where Kenya death rates from unsafe abortions is the highest in East Africa. Statistically, 2600 Kenyan women die as a result of complications resulting from unsafe abortions annually. On average, this comes to seven deaths a day.

Lack of guidelines impedes the Constitution

The Ministry of Health has failed to adopt the Standards and Guidelines on reducing morbidity and mortality associated with unsafe abortion in Kenya even though Article 26 (4) of the Constitution of Kenya permits termination of pregnancy under specific conditions—like rape. Restrictive laws and policies around abortion create a hazardous gap that will continue to cost lives unless redressed.

Following the Malindi High Court’s 2022 ruling that affirmed that safe termination of pregnancy is a fundamental right under the Kenyan constitution and that arbitrary arrests of termination of pregnancy providers and seekers is illegal, Evelyne Opondo, then Senior Regional Director for Africa at the Center for Reproductive Rights said that “the continued restrictive abortion laws inhibit quality improvement possible to protect women with unintended pregnancies.”

Adding to this complexity is the traumatic experience of rape survivors, who often find themselves emotionally and psychologically unable to navigate the intricate legal and administrative procedures required to obtain a legal termination of pregnancy. This forces the victims of rape into a double jeopardy—first as victims of sexual violence and then as casualties of a system that fails to protect them adequately in the event they choose to terminate the pregnancy.

To understand how disastrous and dehumanising it all gets, let’s take the heartbreaking case of Jay*, an impoverished 14-year-old rape survivor from rural Kisii County. Knowing she would be rejected and alienated by her community if she carried a pregnancy conceived from a rape ordeal to full term, Jay confided in an older female acquaintance, who connected her with an unqualified abortion provider who unsafely induced an abortion twice.

However, Jay could no longer hide her predicament from her family upon experiencing post-abortion complications, a reality that is more often than not expected to transpire courtesy of the concomitant dangers of unsafe abortions. Stepping in at this belated juncture, Jay’s mother took her from clinic to clinic in search of medical attention to deal with the resulting heavy bleeding and vomiting.

Unfortunately—and sadly expectedly—the interventions Jay received were both inadequate and ineffective, because the medical practitioners she was referred to neither had the training nor the guidance to effectively respond to her health emergency. In the end, Jay was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease that developed after she experienced haemorrhagic shock following her unsafe abortion. As a result, Jay passed away in 2018. FIDA-Kenya used Jay’s experience to legally challenge the Director of Medical Services in court for withdrawing the Standards and Guidelines for reducing morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortion in Kenya.

As a direct result of the challenge precipitated by Jay’s death, in 2019, the High Court directed the Director of Medical Services to reinstate the Standards and Guidelines on reducing morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortion in Kenya. Four years later, despite numerous court rulings that affirm the constitutional right to abortion, and demands communicated by activists and concerned citizens, the Ministry of Health is yet to adopt the guidelines and ensure medical practitioners are adequately trained to respond to unsafe abortion-related complications and Kenya’s legislature is yet to develop a policy that enables safe access to abortion for Kenyan women.

It goes without saying that Jay and May did not suffer an isolated tragedy; their ordeals represent the alarming continuity of lost lives, shattered families, and unfulfilled dreams that emerge in the wake of the state’s failure to affirm women’s constitutional rights.

Termination of pregnancy seekers are not careless

The foregoing unsafe-abortion-related deaths and tribulations notwithstanding, the Kenyan discourse around termination of pregnancy is often marred by damaging stereotypes. Much as there may be no comprehensive statistics on the number of terminations of pregnancy that are induced annually, according to the APHRC, 64.4% of the women who seek medical attention for post-abortion complications are married or living with their partners.

This thus debunks the notion that many women who seek out an abortion are careless or promiscuous—caricatures often stigmatised by society, since most are already mothers and wives struggling to provide for their existing families; resilient women grappling with agonising choices presented by their limited time, access to resources and access to contraceptives.

A Call to Action

On this International Safe and Legal Abortion Day, let’s honour Jay, May, Job and the untold numbers of Kenyan women and families who share in their dire circumstances. Let’s campaign for healthcare that encompasses safe, legal termination of pregnancy as provided for under the Constitution—free from societal prejudices and financial obstacles.

We can learn from the work of South African activists who successfully campaigned for the 1996 Choice in Termination of Pregnancy Act which guarantees the right of all women and people with the capacity to become pregnant to terminate pregnancies within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Between 1994 and 2001, South Africa saw a 90% decrease in morbidity related to unsafe abortions. A study on Mexico City, which legalised termination of pregnancy in 2007, estimated that costs related to post-abortion complications would decrease by 62% following legalisation. The time for change in Kenya is now! We must act decisively to safeguard the lives and futures of our mothers, sisters, and daughters. Their lives, and the well-being of our families and communities hang in the balance.

*Names have been changed for anonymity.

PS.

For more information and to get involved, visit Love Matters Kenya. To learn more about the global struggle to increase access to safe termination of pregnancy follow our campaign through the hashtag #HealthforAll.