Whether he ascends to Kenya’s presidency on August 9 or not, at 55, deputy president William Samoei Ruto has done the impossible. This is partly courtesy of safeguards entrenched in the country’s 2010 Constitution – which prevented President Uhuru Kenyatta from sacking Ruto or forcing him to resign – and partly thanks to Ruto’s own grit, raw ambition and indefatigability, powered by a corresponding financial war chest which has sustained Ruto’s five year State House bid.

In Kenya’s post-independence history, the vice presidency – as the role was known before the 2010 Constitution redesigned and renamed it to deputy president, elected alongside the president – was considered a poisoned chalice; occupy at your own risk. The role was appointive, meaning the president could and would whimsically hire and fire their second in command or push them to resign.

It took William Ruto to give the role some gravitas.

To his credit, Ruto knew he either had to be preemptive and launch his presidential offensive immediately after he and Kenyatta were sworn in for a second and final term in office on 27 November 2017, or his chances at emerging as a serious contender to succeed Kenyatta would dwindle. The downside was that Kenyatta saw Ruto’s early campaigns as an act of sabotage, because focus would go into Ruto’s election bid to the detriment of Kenyatta’s legacy projects.

To Ruto, signs that Kenyatta would either renege on his promise to back Ruto or that Kenyatta lacked the bandwidth to use his presidential advantage to Ruto’s electoral benefit in 2022 were already manifest in 2017.

Ruto’s calculation was for him to have a head start against Raila Odinga, an old hand in the game who had already run for president four times. Kenyatta’s cageyness and laissez faire manner wasn’t giving Ruto confidence. But beyond Kenyatta’s style, Ruto was triggered by something else.

On 1 September 2017, Kenya’s Supreme Court nullified Ruto’s and Kenyatta’s 8 August 2017 presidential victory following a petition by Odinga. The country was on tenterhooks, with Odinga further declaring that he won’t participate in repeat polls as ordered by the court unless the electoral commision was overhauled. A constitutional stalemate was imminent. Shaken, Uhuru Kenyatta capitulated.

‘‘I would have slapped him if I could,’’ Ruto is heard saying in a recently leaked audio-recording* of him narrating how he coerced President Kenyatta, who was ready to vacate the presidency, to not surrender. ‘‘I couldn’t have let him let the presidency go after the amount of work we’d put in.’’

To Ruto, this felt like deja vu.

In 2013, Ruto and Kenyatta had crimes against humanity charges hanging over their heads at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Five years earlier in 2007, Ruto was in Odinga’s corner while Kenyatta backed Mwai Kibaki for president. But when the vote was botched and the country went up in flames, it was Ruto and Kenyatta who became the fall guys for their respective camps.

Consequently, Ruto fell out with Odinga, and as the 4 March 2013 general election approached, Ruto and Kenyatta decided to each run for president.

As Ruto and Kenyatta were building momentum separately for their respective bids, talks were ongoing within their inner circles about a potential joint ticket. After all, considering the weighty matters at The Hague, they could either stick together or hang separately.

However, just as talks were crystalizing, Uhuru Kenyatta called a press conference, with Ruto in attendance, and signaled his withdrawal from the presidential contest. It later emerged that Kenyatta had signed a memorandum of understanding with Musalia Mudavadi – the Mr. Harmless of Kenyan politics, to support Mudavadi for president.

But before the ink could dry on the deal between Kenyatta and Mudavadi, Kenyatta’s loyalists pitched at his residence, to talk him out of pulling out of the race. Kenyatta listened.

In a shocking comeback days later, Kenyatta told the country that he must’ve been mistaken, misled by demons, for him to want to drop his presidential bid. It felt surreal.

Kenyatta and Ruto went on to win the presidency.

And so the fact that Kenyatta was willing to once again pack his bags and leave State House in 2017 following the Supreme Court verdict, just as he was ready to drop his bid in 2013 under the weight of the charges at The Hague, was one too many red flags for Ruto to ignore. Ruto started putting his ducks in a row – he wielded considerable clout in parliament, and had the Speakers of the Senate and the National Assembly on his side.

At this juncture, word in the political grapevine was that if it came down to it, Ruto could garner the numbers to impeach Kenyatta – if he could convince Odinga to lend him his opposition MPs, to combine forces with Ruto’s allies within the ruling party. Kenyatta has since opined that Ruto was planning to derail the executive using the legislature.

Possibly, Odinga, who had sworn himself in as The People’s President on 30 January 2018 as he continued to protest against Kenyatta’s electoral legitimacy, could have been open to the idea of impeaching Kenyatta. After Odinga boycotted the repeat elections as ordered by the Supreme Court, Kenyatta had run against himself and gotten sworn in. Odinga wouldn’t recognize Kenyatta.

Could Ruto find an ally in Odinga?

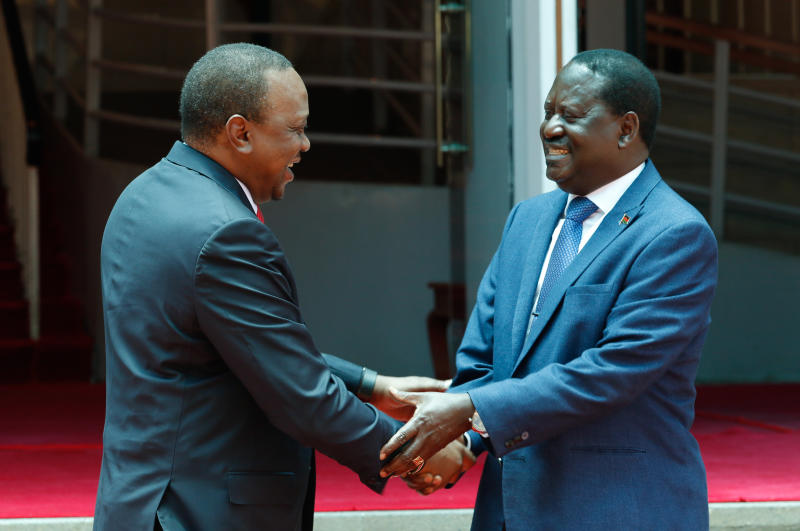

But before Ruto could answer that question, an evidently lameduck Kenyatta beat Ruto to it. As Kenyatta’s men were calling for Odinga to be charged with treason for swearing himself in as president, on 9th March 2018, Kenyatta showed up at the steps of his Harambee House office with Odinga in tow, shook hands and announced a ceasefire.

There was pin drop silence.

Invoking the spirits of their fathers in a terse communique – Kenya’s first president Jomo Kenyatta and his vice president Jaramogi Oginga Odinga (who Kenyatta made to resign barely two years after independence, and who was consigned to house arrest later, never to recover politically until after Kenyatta died) – Uhuru and Raila conceded that the rain started beating Kenya when their once-upon-a-time comradely fathers fell out, and that now, the two sons wanted to atone their father’s sins and fix Kenya. There couldn’t have been a bigger political gesture.

It was game over for William Ruto. Or was it?

William Samoei Ruto was born in 1966 in Kenya’s Rift Valley, where he had a typical rural upbringing relying on farm life for sustenance. For Ruto, chicken held a special place, and still does.

*

Ruto’s home was a walking distance to the infamous Kamagut Junction, where the road leading to Kitale, one of the colonial White Highland sites preferred by Boer farmers joins the Trans-Africa Highway, running from the Mombasa port to Malaba at the Kenya-Uganda border.

The strategic location of the Kamagut Junction, where tens of trucks passed by the hour on their way to Uganda, South Sudan, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo and back, meant that locals had a ready roadside market for their produce.

Ruto’s commodity was chicken. Inhabitants of Western Kenya, known for their liking for chicken, also made the spot a regular pitstop on their way to and from Nairobi. Ruto speaks proudly of his chicken-seller days.

Out of the distraction from moonlighting as a boy-trader, for his O Levels, Ruto managed to gain admission to the nearby Wareng Secondary School, from where he landed at the elite Kapsabet Boys for his A Levels. Thereafter, Ruto was admitted to the University of Nairobi for a BSc (Botany).

A path was forming.

By the time Ruto joined the University of Nairobi in 1986, the Student Organization of Nairobi University (SONU) was just about to be banned. Wafula Buke – who was later seconded by Odinga to become Ruto’s personal assistant when Ruto became minister for agriculture and Odinga was prime minister – led student protests after he was blocked from assuming the SONU presidency, accused of being a Libyan spy. Buke was arrested and SONU was banned.

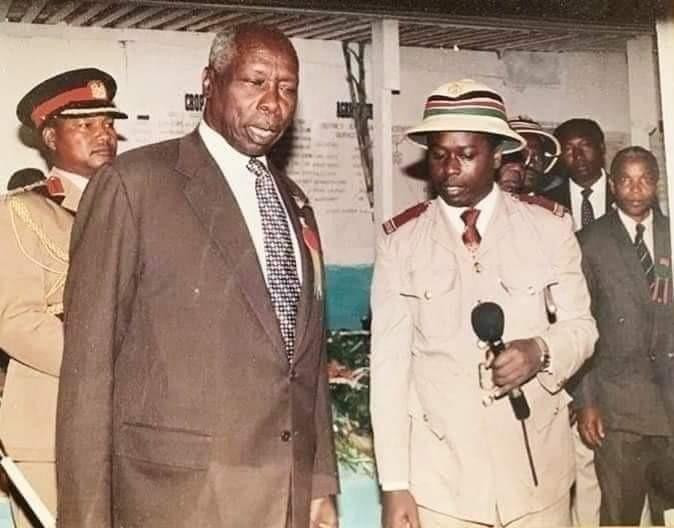

With SONU out of the picture, students retreated to ethnic enclaves, where district associations became their primary organizing units. At the time, strongman President Daniel arap Moi was facing massive pressure from pro-democracy groups, and thereby enlisted the services of these district formations to recruit political foot soldiers for his regime.

It thus became a common occurrence for students to visit Moi under the auspices of these collectives. One of the leaders of these student entities was Rigathi Gachagua, Ruto’s current running mate, who like many others was recruited into Moi’s civil service, at one point serving as the personal assistant to the head of civil service. It was thus no surprise that when Moi handpicked an uninitiated Uhuru Kenyatta as his successor in 2002, Moi deployed Gachagua to handhold Uhuru as his personal assistant.

Unlike Gachagua who already knew the ins and outs of state power by the time he graduated, Ruto hadn’t struck it big by the time he left campus. But being the quick learner that he was, Ruto had developed an eye for opportunity.

By 1991, pressure from pro-reform groups led by the likes of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga buttressed by a group of Young Turks comprising his son Raila Odinga and Raila’s current running mate Martha Karua, was becoming unbearable. Moi capitulated and allowed for the return of multipartism.

This meant that since assuming office in August 1978, Moi would be subjected to a presidential election for the first time, not the mockeries his one party state had perfected, where nobody dared face Moi within the party.

31 year old Cyrus Shakhalaga Jirongo entered the scene.

A sharp-witted drop out from a South African university who had attended Mangu High School, one of Kenya’s most prestigious institutions, Jirongo had turned one of the telephone booths in downtown Nairobi into a makeshift office, so that he made and received calls from the booth.

This was until Jirongo met Job Omino, a monied soccer aficionado. During their first meeting, Omino told Jirongo he was either a con artist of great proportions or the smartest young man he had ever met. Wearing a shirt with a torn collar, Jirongo had pitched a million-dollar idea to Omino, and was asking for assistance to get financing.

Jirongo won Omino over, and Omino paved Jirongo’s entry into government financing. By 1991, Jirongo was hobnobbing with Nairobi’s high society, and following in Omino’s footsteps, had similarly become the chairman of AFC Leopards, one of Kenya’s oldest football clubs.

Jirongo was ready for Moi.

The proposition was simple. Looking at the numbers, the opposition could have defeated Moi in the 1992 election – the combined opposition got 64% of the vote. And so aside from Moi’s strategy of splitting up the opposition, Jirongo offered to build a juggernaut of a campaign lobby group, the Youth for KANU 1992, or simply YK ‘92. Jirongo would lead the group in campaigning for Moi across Kenya.

Moi was impressed. Jirongo assembled the machine.

The YK ‘92 game plan was basic. Splash as much cash as possible in all fissures of the country, with the 500 shillings note, at the time the highest currency denomination in Kenya being the signature amount. By the time the 1992 campaign was coming to a close, that currency note was nicknamed Jirongo, out of how much Jirongo and his YK ‘92 brigade had smothered the country with the note. To date, the source of the YK ‘92 loot haunts Jirongo and his men, and is partly blamed for the ensuing 100% rise in inflation.

26 year old William Ruto was one of Jirongo’s factotums.

Five years later, in 1997, both Ruto and Jirongo made their parliamentary debuts, having become business associates for a time post-1992. Jirongo has openly stated that he ran for parliament to seek protection from the ghosts of 1992, while Ruto has never dwelt on 1992, save for when he is answering Jirongo for claiming that Ruto would have been a nobody had it not been for Jirongo giving him a hand-up.

‘‘I was your handyman, but I made something out of myself,” Ruto has publicly told Jirongo. It wasn’t the last time that Ruto, the student, would become better than the teacher. Daniel arap Moi, Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta can all attest to this. Ruto learns quickly, and moves even faster.

*

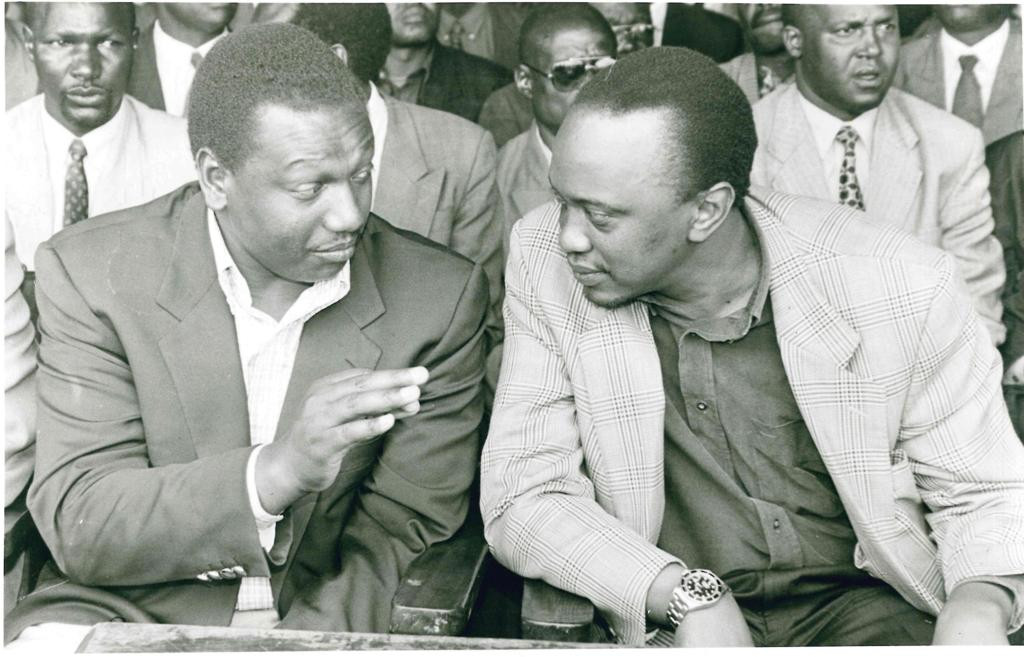

As part of his grand scheme to groom Uhuru Kenyatta as his successor, in 2001, President Daniel arap Moi nominated Kenyatta to parliament, and made him a cabinet minister.

William Ruto was already an MP, who later became a deputy minister and minister for home affairs. Ruto and Kenyatta quickly became bonhomies, with Ruto sticking with Kenyatta after Moi named Kenyatta as his preferred successor, precipitating the implosion of independence party the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which had merged with Raila Odinga’s National Development Party.

Despite losing the presidency to Mwai Kibaki in 2002, both Ruto and Kenyatta retained their parliamentary seats, and took up the role of opposition. And when Mwai Kibaki attempted to impose an unpopular constitution on the country in 2005, in the process falling out with Odinga, who led the onslaught against the state at the referendum, both Uhuru and Ruto sided with Odinga.

It was out of the highly divisive 2005 referendum that Kenyatta and Ruto went separate ways in 2007, with Kenyatta backing Kibaki, his baptismal godfather, for reelection. Ruto, who expressed interest to contest against Odinga for the presidential ticket in their new political party, the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), was coming of age and coming into his own as a consequential national figure.

And because Kenyan politics is organized regionally and thus ethnically – where regional kingpins are propped into the national stage by their home bases for them to either compete or negotiate with other chiefs – Ruto needed to become the leader of his Rift Valley backyard for a start.

At the time, retired President Daniel arap Moi was still the man controlling the Rift Valley. But after Moi’s national heir Uhuru Kenyatta lost the 2002 election to Kibaki, then went ahead to make an about-turn to not run for president in 2007 but instead support Kibaki, Moi had little play.

Kenyatta’s calculation, which paid off, was that because both he and Kibaki came from Central Kenya, it would be prudent to support Kibaki for a second and final term in 2007, after which Kibaki would support Kenyatta in 2013.

Riding on Odinga’s national momentum – Odinga created the Pentagon, the highest structure in the party containing five regional kingpins, with Ruto sitting in for Rift Valley – Ruto capitalized on the fog around Moi and dislodged him as boss. Odinga won the party’s presidential ticket, after which he and Ruto made Rift Valley the party’s stronghold.

And because crises create leaders, the consequent 2007 post-election violence, which heavily affected the Rift Valley, further catapulted Ruto into the national stage and firmed up his chieftaincy. When Odinga and Kibaki agreed to hold talks to contain the violence, Ruto was one of Odinga’s emissaries, while Odinga’s current running mate Martha Karua was Kibaki’s. In the subsequent government borne out of the talks, with Kibaki as president and Odinga as prime minister, both Ruto and Karua made cabinet, with Uhuru Kenyatta as Kibaki’s pick for deputy prime minister.

Kenyatta and Ruto reunited.

For Odinga and Kibaki, their biggest agenda was to usher in a new constitutional order, to prevent Kenya from sliding back into electoral violence come 2013. But the moment Odinga and Kibaki presented a draft constitution, Ruto broke ranks with Odinga and led opposition against the document. There was no coming back from this.

In the midst of the constitutional push and pull, Odinga suspended Ruto from cabinet over corruption allegations, but Mwai Kibaki overruled the decision, saying Odinga lacked powers to punish members of cabinet. As a middle ground, Kibaki agreed to move Ruto from the budget-heavy ministry of agriculture to the less glamorous ministry of education. Still, Ruto wouldn’t toe Odinga’s line.

Eventually, on 19 October 2010, Ruto was kicked out of cabinet after a court found he had a case to answer in a matter where he was accused of defrauding a government agency by selling a piece of government forest land to it.

And since when it rains it pours, a bombshell landed.

On 15 December 2010, Luis Moreno Ocampo, the Argentine prosecutor at the International Criminal Court, opened an envelope and revealed six names, among them Ruto’s and Kenyatta’s. The names, given to Ocampo in a sealed envelope by former United Nations Secretary General Koffi Annan on 9 July 2009, had been zeroed in by a Kenyan commission of inquiry into post-election violence, which had handed its deductions to Annan. Annan had given Ocampo the envelope and asked him to hold onto it, and only act if Kenya failed to undertake a judicial process to redress the post election violence cases within a year.

Mwai Kibaki stood by Kenyatta. Odinga wouldn’t have Ruto’s back. In his tribulations, the Rift Valley embraced Ruto. The conditions were ripe for a coronation. If he could survive the furnace and come out alive on the other side, William Ruto would become the undisputed king of the Rift Valley.

*

When Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto took power in April 2013, the dynamic duo, as the press called them, made a habit of wearing matching pants, shirts and ties, and even agreed to fold their shirts’ sleeves Obama-style. No sensible bookmaker could have predicted a fall-out five years later.

Considered Kenyan royalty courtesy of his father being Kenya’s first president, Uhuru Kenyatta’s ascension to the presidency seemed like a birthright. However, for Ruto, coming from the bottom to becoming deputy president at 47 was no mean feat. Ruto folded his sleeves and got to work.

For their first term in office, Ruto was hands-on to a point where Kenyatta’s presidency had all indicators of a co-presidency. As the agile and teetotaler Ruto became more present, attentive and active, he acquired massive political clout, in a way becoming the face of government.

Ruto’s official residence in Karen, now dubbed ‘the Hustler’s Mansion’ – which morphed into his unofficial campaign headquarters after he fell out with Kenyatta in 2018 – became one of the busiest government installations as it played host to a series of high profile meetings, where far reaching government decisions were made.

Ruto had all the markers of a president-in-waiting.

But not everyone was happy.

As the 2017 general elections drew close, murmurs started surfacing from Kenyatta’s corner. First to speak was David Murathe, Kenyatta’s friend and confidant, handpicked as vice chairman of Jubilee Party, the behemoth Kenyatta and Ruto formed after merging their respective parties.

Speaking in parables initially, Murathe started complaining about a group of highly placed individuals in government who were perpetuating grand corruption, and who seemed entitled to Uhuru’s presidency as if it were a co-presidency.

It was easy to decode Murathe’s message.

As if to send a further warning shot, Murathe went on TV talk shows and divulged that upon re-election, Kenyans would see an Uhuru Kenyatta like they hadn’t seen before; firm and in-charge. Murathe went on to reason that Kenya was ripe for a benevolent dictator, since Kenyatta had been too lenient with wayward fellows in his government.

Everything David Murathe said came to pass.

On making peace with Raila Odinga and having Odinga’s MPs on his side, Kenyatta went on a systematic onslaught against Ruto, including transferring responsibilities initially undertaken by Ruto to the office of Dr. Fred Matiangi, the minister for interior. Ruto’s in-tray became empty.

In the same breath, anti-corruption agencies started pursuing individuals within the state, most of whom cried foul that they were being targeted for being Ruto’s friends.

One such individual was Rigathi Gachagua, Kenyatta’s former personal assistant and Ruto’s running mate, who was accused of siphoning millions of dollars from state coffers through proxies. On 28 July 2022, with campaigns underway, a court granted orders to the state for the seizure of Gachagua’s $2 million from bank accounts, on grounds that the funds were proceeds of corruption.

In the Senate and National Assembly, Ruto’s men were purged from leadership roles at all levels, and were replaced by Kenyatta and Odinga allies. Finance minister Henry Rotich, considered a Ruto man, was sacked and charged with graft in a case concerning the procurement process for the building of two mega dams in the Rift Valley.

From the time he became an MP in 1997, William Ruto had slowly built a business empire straddling insurance, real estate, hospitality and agriculture. And as an ode to his young self, Ruto established a highly mechanized chicken farm, which he partly credits for his financial liquidity whenever he is questioned about the source of his wealth.

In 1971, Kenyan public servants were officially permitted to double in business, and so like many others, Ruto wasn’t shy to do business with the government. In the course of some of these dealings – like the case of him being accused of selling government land to a government agency – the impression that Ruto was corrupt started sticking.

These were escalated by a court verdict where Ruto was found guilty of occupying a 100-acre piece of land in the Rift Valley which belonged to a victim of post-election violence, a case in which Ruto pleaded innocence, claiming he was misled into buying the land. The same line of defense applies in a piece of land next to Nairobi’s Wilson Airport, where Ruto constructed a hotel, which Kenya Airports Authority (KAA) land Ruto says he bought off a third party.

Corrupt or not, William Ruto pushed back.

As Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga started showing a semblance of a co-presidency much as Odinga had no formal state role, Ruto went underground and hit the campaign trail. Traversing swathes of the country with a special interest in Kenyatta’s Central Kenya base, Ruto branded himself a hustler, and christened Kenyatta, Odinga and other sons of politicians as dynasties.

According to Ruto, dynasties must fall.

Two individuals became Ruto’s motif, mama mboga – the vegetable vending market woman, and the boda boda – the motorbike taxi. To Ruto, these two embodied the struggles of the common Kenyan, travails which an Odinga or a Kenyatta couldn’t relate with. After all, Ruto hawked chicken.

In Ruto’s view, Kenyan politics had always been reduced to which ethnic chief was forming an alliance with which other regional kingpin. But to Ruto, the 2022 general election was supposed to be fought on the premise of who cared for mama mbogas and boda bodas, and who didn’t.

Ruto’s rationale was simple. If he could commit class suicide by disowning the polical class then succeed in exciting the working masses at the bottom of the economic pyramid against the Kenyatta-Moi-Odinga establishment (Moi’s son Gideon, a senator, was seen as a potential successor to Kenyatta), then Ruto would have resolved the headache of having to negotiate with ethnic chiefs, since his economic liberation message would have reached the people directly.

On the realpolitik bit, Ruto knew his pseudo-revolution could face setbacks, and so as a backup, Ruto camped in Kenyatta’s Central Kenya backyard – without Kenyatta’s blessings – and sought to build a deeper connection with the voters who he had interacted with closely in 2013 and 2017. This way, Ruto could inherit the support base he and Kenyatta relied on to compete against Odinga twice.

But because old habits die hard, Ruto also revisited his Youth for KANU ‘92 training, and unleashed humongous amounts of money that no other politician – even royalty like Kenyatta and Odinga – could match on the campaign trail. The money came in form of contributions to churches and campaign facilitation for Ruto’s brigade, largesse which only furthered the narrative that Ruto was corrupt.

To cap it off, Ruto’s tongue became razor-sharp as the election drew close, so much so that neither Ruto nor his running mate were afraid to speak directly to President Kenyatta from the podium of political rallies, and spew things no one could have imagined a deputy president and his running mate would ever utter. Uhuru Kenyatta reciprocated.

William Samoei Ruto had placed his bet.

*Ruto has publicly owned up to the leaked audio-recording.

An edited version of this article was first published in The Continent, the award-winning pan-African newspaper.

Subscribe for free here: https://www.thecontinent.org/subscribe