On Thursday, 15 July 2021, conservationist and environmental activist Joanna Stutchbury was shot dead meters away from her home in Thindigua, Kiambu County, a killing which had all the hallmarks of a contract killing. Before her execution, Stutchbury had stubbornly ruffled the feathers of land grabbers and developers encroaching on Kiambu forest and its wetlands. The autopsy revealed that the 67-year-old woman was shot six times at point-blank range.

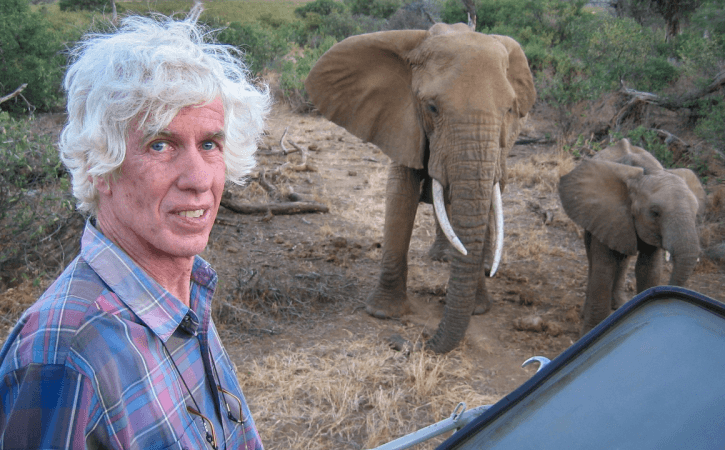

Stutchbury is not the only victim to be killed in the foulest of ways for her stance against environmental crimes. In 2018, Esmond Bradley Martin was stabbed to death at his home in Langata. Martin was a top investigator on matters of ivory trade, and his work shed light on the illegal trade of ivory and rhino horns in East Africa.

The Range of Crimes

Environmental crimes range from poaching, illegal logging, dumping hazardous waste, and trading protected wildlife such as the jaguar. According to the Financial Action Task Force, environmental crimes are a “low risk, high risk” venture because perpetrators often walk scot-free. It is also the fourth largest criminal enterprise in the world, ranked higher than the smuggling of arms.

In Kenya, the environment is protected under laws and regulations set by the Constitution and the National Environment and Management Authority (NEMA). These include the ban on the use of plastic bags and the ban on poaching.

Yet since time immemorial, Kenya has stayed on the wrong side of this fight. Even though the country’s economy is boosted by hordes of tourists who come to set sight on wildlife, visit the actively benign highlands and devour the coastline, perpetrators continue to cause damage to the wildlife and the environment, including going after anyone and everyone who speaks up.

Speaking Up, Threats Notwithstanding

In recent times, one Phyllis Omido rubbed environmental criminals and the government of Kenya the wrong way after her activism against the existence of a battery smelting plant which emitted fumes laden with lead, which was located next to Owino Uhuru, an informal settlement in Mombasa. Omido’s activism proved successful, and the smelter, Metal Refinery EPZ, was closed in 2014. In addition, victims of the lead poisoning in the Owino Uhuru neighbourhood were awarded Ksh 1.3 billion as compensation by the courts.

Wangari Maathai Showed Us the Way

In 2004, the late Nobel Laureate for Peace Prof Wangari Maathai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo for ‘‘her contribution in sustainable development, democracy and peace’’, work which she undertook through the Green Belt Movement.

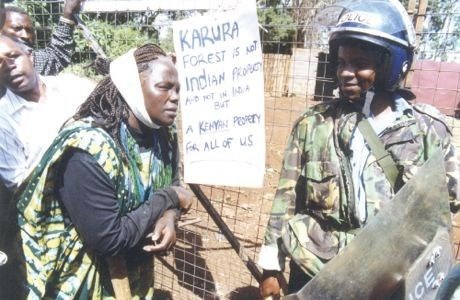

But before becoming a Nobel Laureate, Prof Maathai was considered an enemy of the state by the Kenya government throughout the ‘90s, thanks to her frontline activism against environmental crime. In some notable protests, Prof Maathai lobbied for public support to prevent the ruling party KANU under the one party state from grabbing a section of Uhuru Park where it intended to construct the headquarters of Kenya Times, a newspaper owned by the state. Then there were the Karura Forest battles of the late ‘90s, where Prof Maathai and others stood as human shields against the invasion of the forest by well connected private developers who often deployed armed goons and the police to attack Prof Maathai, her comrades and colleagues. The Green Belt Movement persists.

When Maathai was fighting against the encroachment on green spaces of Uhuru Park and Karura forest, she was opposed by officials ranked high in the government. In fact, in one of President’s Daniel Moi’s speeches, the late statesman referred to Prof. Maathai as a “mad woman”. Maathai was clobbered by policemen in 1999 as she tried to plant trees at Karura forest, and more than a decade later, Phyllis Omido of Owino Uhuru was a victim of the same fate. Omido was once tear-gassed and arrested for “inciting violence and unlawful assembling.”

Indeed, few in Kenya fit Professor Maathai’s bill, but Joanne Stutchbury, just like Phyllis Omido, was a force of her own as she fought to keep off encroachers from the Kiambu forest and the wetlands in the region. Born in Kenya, the white woman’s exploits gained her recognition in 2018 when she posted a photo sitting on a mechanical bucket, with hands on her head in protest against the private land developers in Kiambu forest. Akin to Maathai, who was unpopular amongst the tycoons in Kenya but popular among environmentalists, Stutchbury was lowlily known in the public space until the photo in 2018.

Stutchbury’s murder instigated public outcry locally and internationally, with environmentalists claiming that her murder resulted from her activism. Certainly, their assertions are probable because Stutchbury had said she had received death threats. Moreover, President Uhuru Kenyatta also issued a statement condemning the “senseless killing” of Stutchbury and asked security officers to hunt down the murderers.

However, Stutchbury’s execution reeks of Esmond Bradley Martin’s slaying. Three years later, Martin’s murder remains unsolved, and because of that, the public is skeptical of the justice process. Crimes against the environment could be a low-risk venture because, unlike murder, the victims are wild species, and the repercussions to the inhabitants may not be instant. Still, the justice system, as the conservationists worry, has enabled the execution of environmentalists to be a low-risk venture as well.

Is there any recourse in the law?

It is not that the country lacks the laws to incriminate environmental criminals. According to Shimlon Kuria, an environmental law consultant, the government has perfect laws against ecological crimes.

“The laws against such crimes are there and we have good and progressive laws,” Kuria says. “The problem is in implementing these laws.”

According to Kuria, the “need for development” and throwing caution to the wind hinder these laws’ implementation.

“Despite numerous expert reports on the negative impact of projects of such magnitude such as the SGR and Southern Bypass in a national park,” Kuria says. “The Environmental Management and Coordination Act, 1999 that requires that there be an independent Environmental Impact Assessment before commencement, was not followed to the letter.”

Beneficiaries of these projects are often the elite in the business industry or political sphere. The benefits from environmental crimes are as lucrative as drug trafficking, and Interpol stipulates that when they track environmental criminals, they are often involved in other crimes such as money laundering, tax evasion and fraud.

Kuria thus believes that imprisonment of beneficiaries of environmental degradation should provide a solution.

And it is not just the government to blame for this. The citizenry, too, plays a part in enabling environmental degradation. From littering to buying the banned plastic bags, Kuria maintains that it is not ignorance that the citizens have, but a lack of discipline.

Stutchbury’s murder has shaken the conservation world, and understandably so because history indicates that the government is slacking in protecting the environment and the activists that care.