Lately, Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi’s favorite phrase is Enterprise Kenya, speaking on the need for the country to not merely survive but prosper and satisfactorily fulfil its obligations to its people. But don’t get it twisted. The man who can readily talk shop and drown you in jargon owes his roots to the deepest trenches of the struggle for Kenya’s second liberation, and even if he doesn’t look or show it, remains alive to the painfully peasantry background he came from. In this comprehensive longread, journalist and Debunk Media’s Editor-in-Chief Isaac Otidi Amuke replays his just over two hour conversation with Kituyi, as the former UNCTAD Secretary General shares his trials, tribulations, triumphs, and ideas on Enterprise Kenya.

Part 1: Getting in Good Trouble

When Daniel arap Moi ascended to the presidency of Kenya in October 1978, 22 year old Mukhisa Kituyi was a buoyant third year student studying Political Science and Philosophy at the University of Nairobi’s School of Social Sciences. As an impressionable Kituyi wallowed in the seductions of ideology on one hand and pragmatics on the other – ideas bandied around by a cadre of young professors who fancied Kituyi’s discipleship – Kituyi was unaware that starting almost immediately, and for the entirety of Moi’s 24 year rule, the Student and the President wouldn’t see eye to eye, and would become ready-made adversaries.

But before Moi’s hammer fell on Kituyi and his five comrades, some good news first.

If we took the hand of time back to 1978 and walked into the University of Nairobi’s School of Social Sciences, snuck our way into the Department of Political Science and assembled Kisumu Governor Prof. Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o, former Head of Civil Service Dr. Sally Kosgey, former commissar in the Social Democratic Party’s politburo Dr. Apollo Njonjo and the highly decorated scholar Prof. Michael Chege, and asked them who their favorite undergraduate student is, they’ll all tell us without blinking an eye that that has to be Mukhisa Kituyi. Kituyi modestly hints at this, one of his classmates fully corroborates, and the actions of Kituyi’s aforementioned lecturers in subsequent interactions leave no doubt about this.

‘‘Mukhisa was quite brilliant and outspoken,’’ says Kituyi’s year mate Josiah Apollo Omotto when I reach out to him. ‘‘He topped our Political Science class, researched adequately for tutorials and addressed countless symposia. He was a one man think-tank from as early as those days, so eloquent in both English and Kiswahili.’’ Omotto doesn’t stop there. ‘‘He was also extremely sociable,’’ he says, ‘‘one of the best dancers on campus. Ladies loved him.’’

I take Omotto’s word for it. Few people knew (know) Kituyi the way Omotto did (does).

Before reporting to the University of Nairobi in 1977, Kituyi’s maiden trip to Nairobi was in 1971 courtesy of his cousin, former Vice President Michael Kijana Wamalwa. Wamalwa had brought Kituyi over in an attempt to get him admitted to Starehe Boys Center. Unfortunately for Kituyi, they were time barred, and Kituyi thus ended up lounging at Wamalwa’s Woodley Estate residence, provided by the University of Nairobi where Wamalwa taught Law. This seemed like the perfect precursor for Kituyi’s city and campus life, considering that after joining the university, Kituyi rarely went back to the village, having made friends with Wamalwa’s contemporaries within the teaching fraternity, who took on Kituyi as an apprentice.

‘‘I had the privilege from my first year to have a sense that my teachers appreciated me as an especially engaged person,’’ Kituyi tells me when we speak in his Nairobi living room, sparsely but tastefully furnished with dominant Swahili and oriental aesthetics as to make it seem like the parlour of a hideaway in Lamu, Zanzibar or Marrakech. There’s a Lamu daybed with cosy cushions, to give you an idea. ‘‘There were few graduate students, who were three to four years ahead of me academically, who were being inducted by my teachers into informal private conversations about the state of issues the way I was being taken in.’’

Anyang’ Nyong’o, Sally Kosgei, Apollo Njonjo and Michael Chege adopted Kituyi.

Whenever the university closed, this group of professors would ask Kituyi to stay behind in Nairobi and offer him gigs as a researcher for the various projects they were working on. In the process, Kituyi became an intellectual evangelist, passing on whatever he picked from his teaching faculty benefactors to his peers, with whom he formed study cells. It is to this practice of iron-sharpening-iron between Kituyi and the professors and Kituyi and his fellow students that the man from Kimilili believes he solidified his lifelong con victions as a person.

‘‘In many ways, that period of time shaped the way Kituyi finds footing in society,’’ he says, ‘‘as I ask myself what is my relevance? Will I leave a legacy of pride and say I tried to make a contribution or will I be a mere traveller who sits by and moans how terrible Kenyans are?’’

And then it all fell apart.

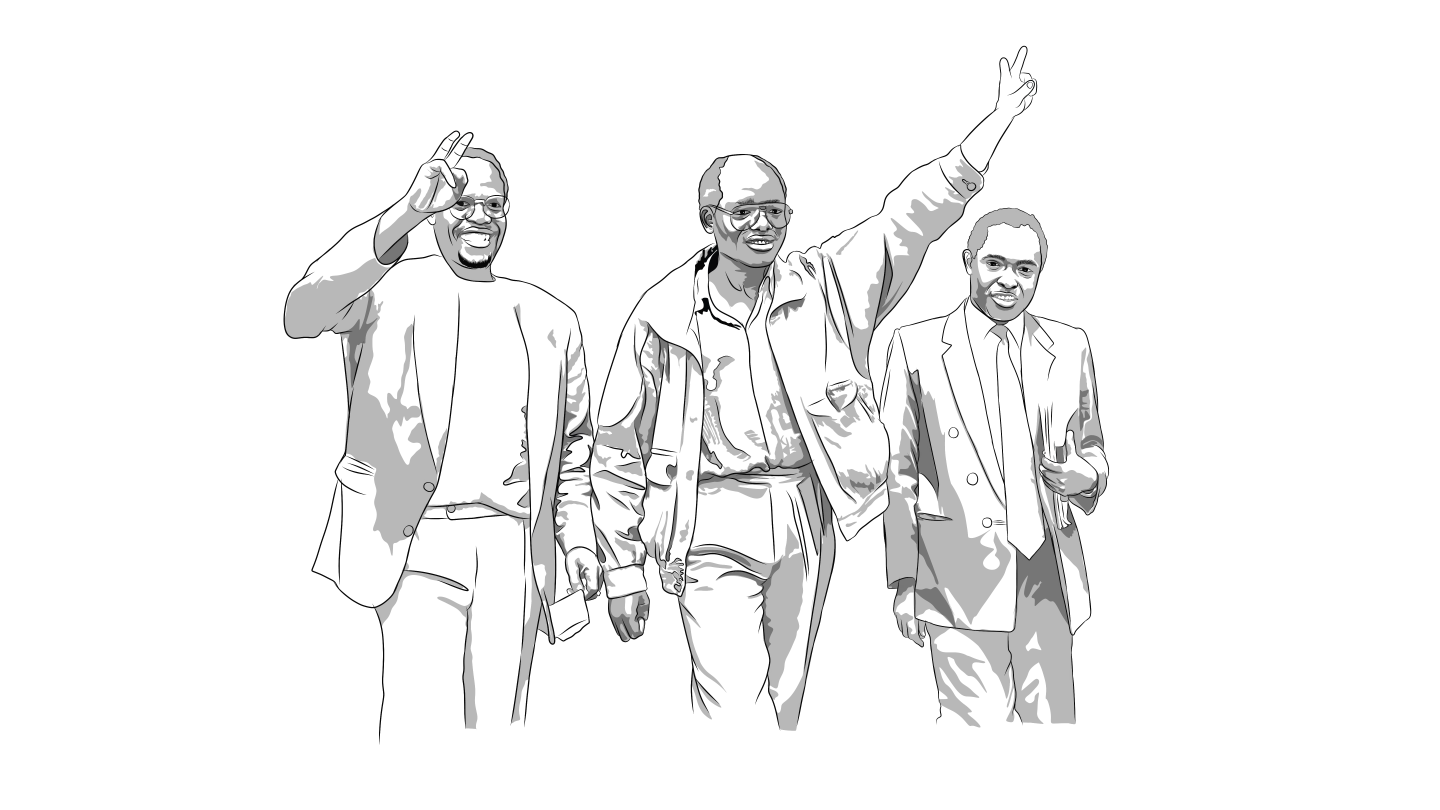

As Kituyi and his comrades were getting all idealistic, President Moi and his KANU brigade expressed intent to make Kenya a de jure one party state, as a reaction to George Anyona’s and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s move to register a political party. Kituyi and others organized and led what Kituyi terms a peaceful demonstration in 1979. Moi struck. Mukhisa Kituyi, Josiah Apollo Omotto, Otieno Kajwang’, Rumba Kinuthia, Karanja Njoroge and Otieno Kungu were summarily expelled from the University of Nairobi, and made enemies of the state.

Kituyi had just entered his final year of study.

As was to quickly become practice as Moi decided to ‘fuata nyayo’, being marked as a sore thumb by the state meant either detention without trial, going underground, self-exile, or for those unlucky, a meeting with one’s maker. The 1979 Six didn’t sit around and wait.

First, Omotto reached out to Henry Okullu – the first Black provost at the All Saints Cathedral and future Bishop of the Anglican Church in Kisumu. Okullu, who had worked in Uganda, activated his networks to try to secure the six lads a place at Makerere University. The other front was opened by Kituyi, who hid in Dr. Sally Kosgei’s home in Ngumo Estate. Kituyi reached out to his teacher Prof. Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o, who in turn got in touch with Prof. Mahmoud Mamdani at Makerere. It was this combination of efforts between Okullu and Nyong’o in Nairobi and Mamdani and Prof. Apollo Nsibambi (future Prime Minister of Uganda) in Kampala that eventually yielded openings at Makerere in 1980 for The 1979 Six.

But before Makerere, there was an elongated purgatory, a true baptism of fire.

As The 1979 Six took cover after their expulsion, it became apparent that they had to leave the country one way or another, lest they fall into police dragnets being set up around their rural homes. Luckily, Omotto had an uncle working as a guard at a government warehouse in Kampala, and so he reached out and embarked on a reconnaissance of sorts before alerting Kituyi and the rest to join him. It was better to starve in Kampala than rot and die in Kamiti.

‘‘I was the first in Uganda, with the support of Bishop Henry Okullu – I can reveal that for the first time today,’’ Omotto tells me. ‘‘Once in Kampala, I connected with certain professors who Okullu had put me in touch with, who started working on our admission at Makerere.’’

Other than Nsibambi and Mamdani, the other two professors were government ministers – Tarsis Kabwegyere and Otema Allimadi. But beyond trying to secure admission for the boys, nothing more was forthcoming from these contacts in terms of material support.

‘‘I did invite the rest over to Kampala,’’ Omotto goes on, ‘‘and we stayed with ..my uncle who was an askari at the Ministry of Commerce headquarters. To make ends meet, we washed staff cars and did other odd jobs. Mukhisa, Okungu and I easily adjusted to the menial jobs while Kajwang’ and Rumba Kinuthia had serious difficulties coping. Later, we were joined by newly expelled student leader James Kokonya, who was equally adaptable. We survived on kichwa na miguu za kuku, big portions of ugali and vegetables, beans and matoke.’’

Kituyi vividly remembers how they spent nights in abandoned cars.

‘‘During the day,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘we walked around Kampala lost, without a sense of purpose.’’

Before they knew it, a year had passed. It was 1980.

By this time, all strings had been pulled and there was general agreement that The 1979 Six should be allowed into Makerere. But then there was one last hurdle. It wasn’t the norm for Makerere to admit expelled students from the University of Nairobi, and so the registrar at Makerere, Bernard Onyango (who Omotto tells me is the father of veteran Ugandan journalist Charles Onyango-Obbo) had to perform one last administrative task.

‘‘Onyango wrote to Nairobi asking whether Makerere should admit us,’’ Omotto recalls, ‘‘we owe it to one individual, Prof. Joseph Muigai, who was the University of Nairobi’s Vice Chancellor, for writing ‘‘Please admit. The university had no problems with these students.’’’’ Clearly, the expulsions had been the work of an overzealous Moi state.

Once admitted at Makerere, Kituyi credits friends of Rumba Kinuthia who introduced them to the UNHCR, which granted The 1979 Six refugee status and partial scholarships. But much as all these elements were getting aligned, there was yet another price for Kituyi to pay.

‘‘The practice across the Commonwealth was that for a student to earn an undergraduate degree from an institution, the said student must have spent at least two academic years there,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘This meant as a third year from the University of Nairobi, I had to go back to second year. I therefore lost two years – one year waiting, then lost a year by going back to second year. My classmates in Nairobi graduated in 1980. I graduated in 1982.’’

Here, Kituyi ropes in divine providence in saying he was the first of his University of Nairobi cohort to earn a PhD, in a sense thereby making up for lost time.

And yet, no matter how difficult life in Uganda was, Kituyi tried to make it bearable by having a social life within budget. It was during one of these boozing rendezvous that Kituyi experienced something he won’t forget in a long time.

‘‘One time we went to join some Kenyan friends at a busaa drinking party in Nakawa,’’ Kituyi narrates. ‘‘It was the time Iddi Amin had been ousted by Tanzanian soldiers, and the new president, Godfrey Binaisa, had also just been deposed. And so as we spoke in Kiswahili, Ugandan agents pounced on us, on suspicion that we were Tanzanian operatives.’’

Kituyi and his friends were taken into a military prison, where Kituyi says he could see pieces of human flesh, broken bones and human blood splattered across the cell.

‘‘It took some time before we could prove that we were Kenyan students,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘and it is for some of these reasons that those of us who have seen how failed states can be truly failed insist on caution when it comes to Kenyan politics, to not take things for granted.’’

It was in the midst of navigating school and Uganda’s turbulent politics, Omotto tells me, that Kituyi found a friend in Museveni, who had run for parliament in 1981 and lost, with his party at the time gaining only one parliamentary seat. But Museveni was a young Marxist intellectual fresh from the University of Dar es Salaam, and it is easy to see how he and the likes of Kituyi found points of convergence both politically and intellectually.

‘‘When Museveni protested rigged elections, Mukhisa identified closely with his movement,’’ Omotto reveals, ‘‘and has since sustained rapport with President Museveni’s men to date. Of all of Kenyan politicians, Mukhisa is easily Museveni’s best buddy.’’

At just 26, Kituyi had lived. And yet his entire life lay ahead waiting for him.

Part 2: The Youngest Young Turk

After Mukhisa Kituyi was done with Makerere University in February 1982, bringing back a BA in Political Science and International Relations, Dr. Apollo Njonjo, Kituyi’s University of Nairobi professor, offered him a soft landing as a researcher in his consultancy firm. While working with Njonjo – in a National Water Master Plan baseline study that took Kituyi to all 45 districts in Kenya except Mandera and Kuria – Kituyi made a Norwegian connection, and ended up spending seven years in Norway starting in 1983.

Stationed at the University of Bergen, Kituyi obtained a diploma in Comparative Production Systems – and fell in love with and married a student of medicine at the same institution, Ling Andersen (later Dr. Ling Kituyi) in 1984. Kituyi then turned down an earlier scholarship from Georgetown University in the United States – he had gotten it while in Nairobi but opted to defer – and instead pursued an MPhil and PhD in Social Anthropology still at Bergen.

But before setting off for Norway, the stage for Kituyi’s return to Kenya was set.

At the tail end of July 1982, Kituyi’s friend Koigi wa Wamwere sent for Kituyi and his cousin Michael Kijana Wamalwa to travel to Nakuru for a little chat. When Kituyi and Wamalwa arrived, Koigi told them he had picked from the grapevine that a coup was in the offing, and that he wasn’t sure if he would be safe. With that being said, Koigi informed his two guests that he just wanted his family to know them as his friends, in case the state came after Koigi post-coup.

Kituyi went home.

The following day there was an attempted putsch.

‘‘Some of those things about the early ferments of discontent in the country stuck with me,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘and also mark the point where I significantly started to re-engage with processes of resisting oppressive government, an engagement that I was to carry on for the next 40 years.’’

As it turned out, Kituyi ended up hosting an on-the-run Koigi in Norway not too long after. And as Koigi was in Kituyi’s place, Kituyi shared a draft manifesto of what he imagined could be used to start mobilizing the Kenyan masses. Koigi took the rough notes, made copies and embarked on a series of dispatches of the same into Kenya. The Special Branch got wind of this and started arresting Koigi’s addressees in Malaba and Namanga borders, and charged them with sedition.

‘‘The document wasn’t seditious in any way at all,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘it was still a very rough draft.’’

Kituyi was back in Nairobi in 1989.

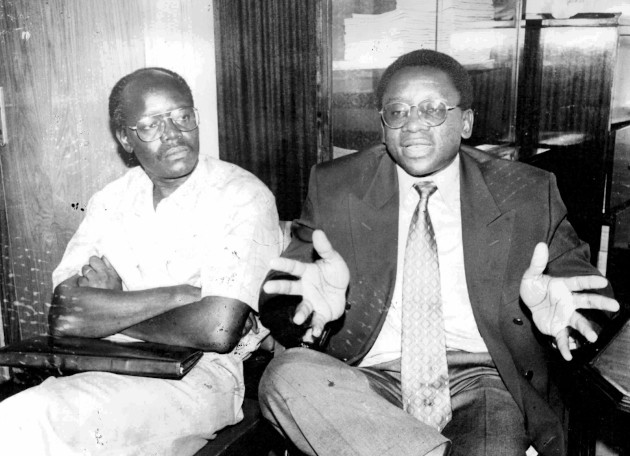

Upon reconnecting with his teacher Prof. Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o, a political cell was quickly born. Working for the Norwegian Agency for International Development (NORAD) at the Norwegian embassy, Kituyi got in-too-deep with the agitators.

‘‘We were a small group of people who were discussing what are the next steps, wondering whether the conditions were ripe for change,’’ Kituyi tells me of the earliest stages of what grew to become the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD). Among them, and Kituyi won’t mention names, were some who fancied the flowery language of the Russian revolution. ‘‘I even remember some doctrinaires saying the Bolsheviks should now take advantage of the numbers of the Menesheviks to have a critical mass and move the process forward.’’

We both burst out laughing.

This group comprising Kituyi, Nyong’o, lawyers Paul Muite, Gitobu Imanyara, James Orengo and Pheroze Nowrojee – and sometimes joined by Joe Ager – was what Kituyi considers the core of what became the Young Turks. Kituyi was at least 10 years younger than the rest.

‘‘Raila had been working with us but when things got very difficult, he had to flee,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘I hid him in my house before my wife and I drove him to the American embassy. The Americans couldn’t take him in, and so he sneaked out of the country through Uganda, and made his way to Norway where his first stop was my father in-laws house as he was seeking refuge.’’

In that initial phase, Kituyi says their discussions were centered on whether Kenyans were ready to be led by an intellectually mature but biologically young team as a coalescing point around which to carry out the struggle for the second liberation. The answer was yes and no. A decision was made – which in hindsight Kituyi sometimes regrets – to bring in older leaders with whom to build a broader coalition, strong enough to shake the foundations of the powerful Moi state.

‘‘A critical moment of decision making, rightly or wrongly, expanded our ranks from this group called the Young Turks, to now bring in Jaramogi Oging’a Odinga and his inner circle; Masinde Muliro – who came with Musikari Kombo, Michael Kijana Wamalwa and George Kapten,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘Kenneth Matiba was abroad, but because there was talk of him running we invited his people, represented by the likes of Philip Gachoka, Martin Shikuku and Japhet Shamalla.’’

By this time, Kenya had severed diplomatic ties with Norway, and Kituyi’s program at NORAD had come to a halt. Kituyi found a job at the Calestous Juma-led African Center for Technology Studies (ACTS). It was while at ACTS that Kituyi’s dalliance with the Young Turks proved costly. Two board members, former Supreme Court Justice Prof. J.B Ojwang and Prof. Hastings Okoth Ogendo pushed for Kituyi’s resignation, on grounds that he was associating with dissidents.

‘‘Prof. Ojwang and Prof. Ogendo started applying pressure on Calestous that Kituyi is a rebel, an enemy of the government who is dealing with enemies of the government,’’ Kituyi says, insisting he wants this fact recorded, ‘‘he should either cut ties with them or leave ACTS.’’

Kituyi’s stay at ACTS became untenable. He was made to quit, and gave himself to the struggle.

As all of this was unfolding, Kituyi remembers a Young Turks meeting where James Orengo proposed the name FORD, which became a pressure group with Kituyi as its Executive Director.

‘‘I was perhaps the only person with a personal computer at home,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘We met in all manner of places, including restaurants, and discussed a wide range of issues. But every time we had resolutions, Pheroze, Orengo and myself were tasked with capturing them. But all documents that were reduced to text were done on my computer at home in Mountain View.’’

At this time, the cracks in FORD were emerging. Jaramogi and Matiba were pulling in different directions, with Muliro making an effort to narrow the rift between the duo.

‘‘A lot of people don’t understand just how averse Muliro was to controversy,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘We even had a joke as the Young Turks that whenever there was a hard decision to be made or some of us hotblooded folk wanted to escalate things politically, Muliro was to be found doing a pilgrimage to the Holy Family Basilica, to meditate and pray for a non-controversial breakthrough with Cardinal Maurice Otunga.’’

Unfortunately, Muliro died before Jaramogi and Matiba closed ranks. Thereafter, two splinter groups emerged, domiciled at Jaramogi’s Agip House and Matiba’s Muthithi House offices. The factions became known as FORD-Agip and FORD-Muthithi, before FORD-Agip became FORD-Kenya and FORD-Muthithi morphed into FORD-Asili. All the Young Turks, without exception, sided with Jaramogi and went into what became FORD-Kenya.

I ask Kituyi why the Young Turks followed Jaramogi en masse.

‘‘Neither of them (Jaramogi and Matiba) was saying all the things we wanted to hear,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘But of the two, Jaramogi was more willing to listen to us and be more accommodative. But on Matiba’s side, our impression was that they were not interested in listening to ideas but were more fascinated about building a movement around a personality.’’

And with that, FORD-Kenya and FORD-Asili hanged separately during the 1992 general election.

At the time, a FORD-Kenya rally was incomplete unless Kituyi sang. And it wasn’t just any ballads. Kituyi had specialized in particular Daudi Kabaka oldies, which he made a habit of corrupting then perfecting. He would swap the original lyrics with his own satirical compositions – designed to ridicule President Daniel arap Moi and his yes men – then master their rhythms and tempo, delivering them with such effortlessness as if he was Daudi Kabaka’s body double.

Mukhisa calls this jigging during the FORD-Kenya rallies building electricity.

‘‘We were intellectually the finished product,’’ Kituyi says of their prowess and antics. ‘‘But we also knew delivery was important. And so we tried to find the best ways to engage the crowds.’’

And yet for Kituyi, there was more to the singing than met the eye.

‘‘I had a battered Isuzu Trooper, which had no music, nothing,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘and so whenever I drove from Nairobi to Bungoma, I kept myself from dozing off by improvising new lyrics and singing Daudi Kabaka classics. I would then try the songs out on crowds to see if they worked.’’

For other (unnamed for now) Young Turks, getting Kiswahili tutors became necessary. Having the ability to fluently work crowds in both English and Kiswahili was mandatory.

In Kimilili Constituency, Kituyi was facing off with Elijah Wasike Mwangale, a powerful KANU minister and a man of means. Other than his jalopy of an Isuzu Trooper, Kituyi had a little esimba, the one he built while a student at the University of Nairobi. There was not much to write home materially about him. But Kituyi tells me the Bukusu had decided. It was chibili chibili across Bungoma, chibili being two, signifying FORD-Kenya’s two finger salute.

Kituyi made his parliamentary debut at 36, becoming opposition Chief Whip.

‘‘It wasn’t out of any of my doing – my brilliance, my ideology, or my oratory prowess,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘I owe it to the moment and the movement, and can’t take credit that I did anything unique other than stand up in courage to be counted at a time when Kenya needed us.’’

But after everything is said and done about that epoch, a question and a personality linger in Kituyi’s mind. The question is, were the Young Turks right to rope in the older leaders, and the persona is Jaramogi Oginga Oding’a, a man who afforded Kituyi a level of rare trust.

‘‘I think that one of the betrayals we made for the struggle in this country is that when the country was warming up to what we stood for,’’ Kituyi reflects, ‘‘we kind of compromised by surrendering to preexisting factions within the political landscape. Matiba and Jaramogi each represented certain continuities of battles of the yesteryears, which were not ours.’’

Kituyi remembers that it was Raila Odinga, more than anyone else, who urged the Young Turks to venture on their own and chart their destiny – including away from his own father. Paul Muite too entertained this idea, but the rest of the Young Turks seemed to prefer costly pragmatism.

But as they say, hindsight is 20/20.

I ask Kituyi how Jaramogi came to trust him.

‘‘Raila Odinga and Anyang’ Nyong’o cultivated that bond between me and Jaramogi,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘in a way that when we met I could tell him some of the things I thought were useful for him to do. And he accepted. And already very early when we started doing press releases, my owning the first computer in the group meant I prepared some of his speeches, and he seemed happy with what I brought him. In acknowledgement of this, he opened himself up to me,’’

Kituyi tells me that over time, Jaramogi became very candid with a small group of them, up to his death. Kituyi, Orengo and Nyong’o – and sometimes Muite – had also become very close.

‘‘He told us some very intimate things,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘which have remained off the record but which give us a sense of who we are and what were the pitfalls in Jaramogi’s own reckoning.’’

I ask Kituyi a question.

Does the secrecy shrouding these conversations feel like there was an oath of silence?

‘‘Almost,’’ Kituyi says without hesitation.

‘‘The last meeting Kijana Wamalwa, Gitobu Imanyara, Paul Muite, James Orengo, Anyang’ Nyong’o, George Kapten and myself had with Jaramogi in his hotel room in Mombasa a week before he died,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘he told us things knowing he was about to die. And he told us he had called us purposefully, and told us very profound things which we’ve never shared with the Kenyan public. It was a thank you and a goodbye meeting as he told us his body clock was slowing down. He thanked us for our service and for making him feel and be young again.’’

Kituyi won’t say anything more than that.

Part 3: Kibaki Liked Him, Ban Ki Moon Wooed Him

Two huge photos usher you into the foyer of Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi’s Nairobi home. The first one has a widely smiling Kituyi posing with Pope Francis, while the second has a jovial Kituyi and his wife, Dr. Ling Kituyi, standing on either side of former United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon.

And when Kituyi walks down the wide wooden staircase on the right hand side of the entryway – he is fully suited and tells us this is the first interview he is doing in his home dressed in a suit – Kituyi embarks on a little house tour, on a mission to help us weigh options for an ideal spot to shoot the interview, seeing that we’d already been let in by Kituyi’s house manager and had set up in his living room. We take cue and look at more spaces, to see whether there’s a better one.

We go into Kituyi’s study, located next to the staircase, where Kituyi takes a seat and meddles with the swanky adjustable table, a room-wide bookcase playing background. We take a few photos of him looking UN-Secretary-General-ish, then walk through the sparsely yet tastefully furnished lounge exhibiting a delicate mix of coastal and oriental aesthetics. We land in the backyard, where Kituyi’s two identical dogs which had jumped all over my colleagues and I and kept tapping the door during the interview try to make a go at Kituyi, but he shoves them aside. They may ruin the outfit, but the affection is palpable.

Then there is the dining area, which looks like one of the rooms at the United Nations – most under-stated with wooden seats cushioned with UN-blue fabric. Throughout the house, there is absolutely nothing that screams extravagance. Everything speaks taste and functionality. In the living room, there are collectibles gathered from Kituyi and his family’s world travels, so that calling them chattel would be an injustice. Memorabilia and souvenirs would be more like it.

It is during this walk-about that Kituyi ventures into a corner of his living room, wanders into the bar, stands behind the counter and asks with a knowing grin, ‘‘How did you like my bar? Some people have come here and gotten obsessed.’’ I wouldn’t blame those people.

As you enter Kituyi’s parlour and look to the far left, what you see is a drinks cabinet with glass doors running from floor-to-ceiling, obstructed by a serving counter. Inside the compartments is a display of all manner of rare bourbons, whiskeys and brandys; entire ranges of Henneseys – including those that cost an arm and a leg; your Glenfidichs and Glenmorangies, and so on. The whiskeys are dominant, possibly testament to Kituyi’s taste if not that of his guests and family.

And for a minute, much as it’s only midmorning, I am tempted to think Kituyi is about to pour my colleagues and I a drink when he drops a few names (which I won’t repeat for obvious reasons) of some of those who’ve drowned in the exploits of his impressive collection. It seems for the well-stocked bar alone, Kituyi gets quite a stream of high profile visitors.

‘‘Is the bar part of who you are?’’ I ask Kituyi, catching him off guard.

‘‘Yeah yeah,’’ Kituyi says after giving it a quick thought, ‘‘in a way.’’

Outside the mansion, Kituyi’s sole white Porsche Cayenne is parked, a world apart from his battered Isuzu Trooper which he used during his first political campaign in 1992. From Kituyi’s demeanor and the aura around his home, one gets the impression that here stands a man who has seen the world, and chosen to leave the world behind and come home, to make home look and feel like the world. But despite this peacefulness, there is a restlessness about Kituyi.

Kituyi’s earliest memory as a child was that of his family rushing out of their grass thatched house and running for a kilometer to a home which had a tin roofed house, to take refuge from on coming attackers from the Sabaot community who were zeroing in on the Bukusu. The logic was that it would take a little longer to burn down a tin roofed house, by which time its occupants would have vacated and disappeared into the bush. The other relayed-memory, as told by his father, was of Kituyi almost drowning in Lake Kyoga in Uganda as a child when his family was on the move, seeking greener pastures. No luxury in the world could erase such from Kituyi’s mind.

‘‘It is a statement of the vulnerability of ethnic tensions,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘always living with the numbing fear that we have unresolved issues which we are not giving attention as a nation.’’

But beyond Kenya’s existential dilemmas, Kituyi carries an awareness from childhood that he always has to fight harder to find his place, for the sole reason that he started school so young – he was his elder brother’s classmate from primary school – which meant he was always less physically endowed than his mates. He was never picked for the class team – they would say, ‘‘Let the kids get off the pitch so the adults can play.’’ It is the same being-much-younger matter that stopped Kituyi from stepping forward to lead FORD Kenya for the longest time, since there were always older brothers in the room who the patriarchal system dictated were next in line to lead.

‘‘I used to wake up at 5am,’’ Kituyi says of his primary school days, ‘‘milk the cows, take milk to the collection point 1.5 kilometers away, walk back home, have porridge for breakfast, then walk 3 kilometers to school. I used to walk a total of 8 kilometers daily, barefoot.’’

The walking didn’t stop after Kituyi left Mbakalu Primary School.

‘‘When I joined Bokoli Secondary School for my O Levels, I wouldn’t look forward to midterms like the rest of the school,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘because I never had any pocket money and couldn’t afford transport home. And so during midterms, I would start walking at midnight, so that I could get home later the following day. After walking the 30 kilometers, I would get home sore and numb and stay sick in bed, and by the time I recovered, it was time to walk back to school.’’

One sees a sense of pain and deep reflection in Kituyi’s eyes as he narrates these stories. Kituyi caught a break at St. Mary’s Yala for his A Levels, and later at the University of Nairobi.

But apart from childhood, Kituyi is grounded by his 7 year stay in Norway, where he experienced the Scandinavian model of social democracy and took up egalitarian habits which he says he has always hoped Kenya could replicate and significantly narrow the socio-economic gap.

‘‘Those who know me will tell you I don’t believe in hierarchical relationships,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘The Norwegian Prime Minister moves around with two guards, and cannot afford domestic staff so they get home and cook for themselves. At the university, you can tell a professor, ‘‘There’s something I wanted to ask you, I wonder if you have time after class so we could meet and talk over a drink.’’ The professor would then ask you, ‘‘What’s your favourite pub?’’ and you can agree to meet somewhere close to the professor’s bus stage, because professors take buses.’’

It is a kind of simplicity and self-sufficiency Kituyi espouses. When we get to his well-secured home, it takes a moment before the gate is opened. Kituyi tells us the groundsman is away and the housekeeper hadn’t heard us ring the bell. Notably, there were no other handymen and women around. Kituyi also shares instances where during golf, he has had to intervene and ask a Court of Appeal judge and an heir to a Kenyan business empire to not be abusive to caddies.

‘‘The Scandinavian model works and has convinced me that it is possible to grow an economy without tolerating extreme inequality, and without blocking opportunities for progress,’’ Kituyi says as he lays down his mini-manifesto. ‘‘You cannot have a section of society in dire misery, totally ignored and sometimes subjected to criminal violence by the state, and then have another section with hundreds of security guards protecting their families and property.’’

*

The death of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga in January 1994 was akin to a shepherd pulling a disappearing act on their flock. The ensuing tug of war between a faction led by Raila Odinga and another led by Michael Kijana Wamalwa, and the consequent walkout by the Raila group, saw FORD-Kenya arrive at the 1997 general election shrunk but still putting on a brave face. Of the Young Turks, Mukhisa Kituyi, James Orengo and Anyang’ Nyong’o stuck with Wamalwa.

The result of FORD-Kenya’s split in the context of a broader fragmented opposition saw Daniel arap Moi win the 1997 presidency with 40% of the vote, just as he had done in 1992 with 36%. Kituyi retained his seat as MP for Kimilili Constituency, and continued serving as opposition Chief Whip. But after the 1997 loss, followed by Raila Odinga’s NDP going into an alliance with Moi’s KANU, Kituyi and others started thinking of how to consolidate a counter force to KANU.

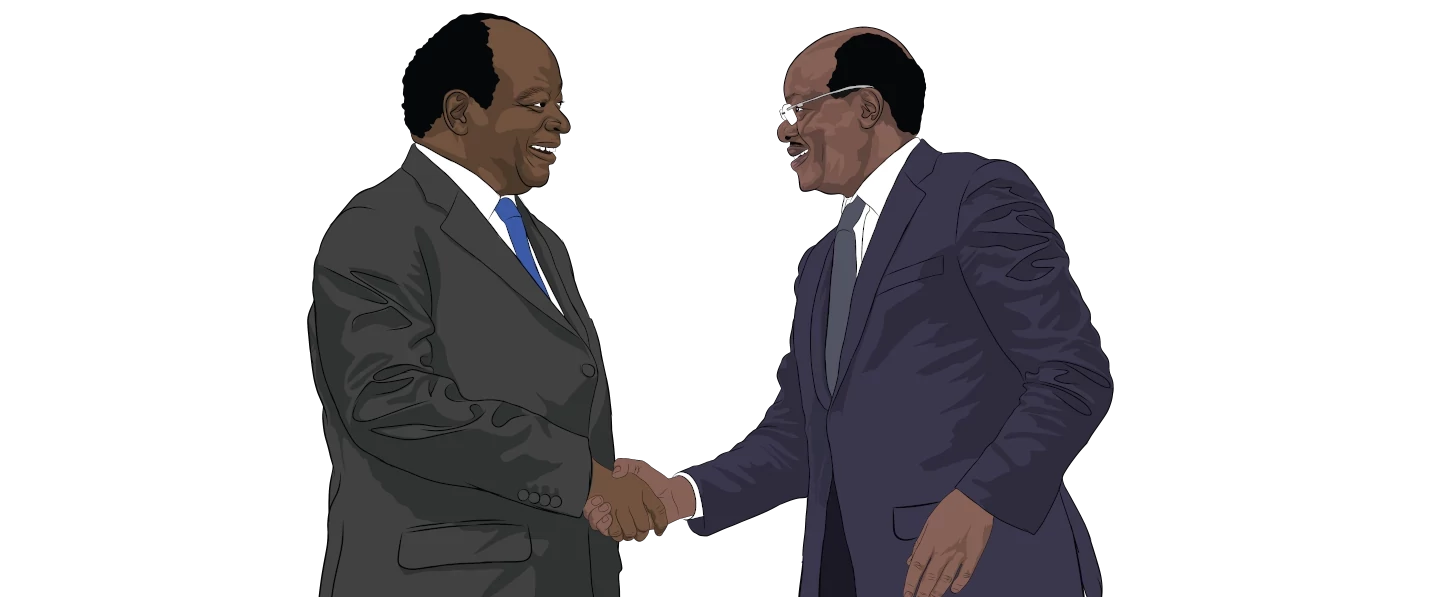

‘‘We had a retreat in South Africa as guests of the African National Congress (ANC), where for one week we tried defining how we could create an agenda that we owned together as parliamentary opposition parties,’’ Kituyi says of the time he properly grew his coalition-building muscle, which he says will come in handy now that he’s seeking others. ‘‘In attendance were Mwai Kibaki, Norman Nyaga, Njeru Ndwiga, Martin Shikuku, James Orengo, Michael Kijana Wamalwa and Pheroze Nowrojee.’’ Part of the original core of the Young Turks – Kituyi, Orengo and Nowrojee were regrouping. A number of diplomatic missions in Nairobi were onboard.

It is out of this caucusing, according to Kituyi, that by the time KANU was imploding and Raila Odinga led a group of luminaries into the opposition, Mwai Kibaki, Charity Ngilu and Michael Kijana Wamalwa had already built sufficient gravitas. To Kituyi, Raila’s ‘‘Kibaki Tosha’’ edict was both a concession and acknowledgement of the opposition’s preexisting momentum. Much as Raila and his new entrants held sway, they couldn’t alter the opposition’s prior covenants.

This is how Kituyi was sworn in as Minister for Trade in Mwai Kibaki’s government in 2003, and FORD Kenya, the party of the Young Turks, was closer to realizing Wamalwa’s infamous ‘Grand march to State House’ when as party leader, Wamalwa was offered the vice presidency as per the pre-election agreement. However, before becoming minister, something happened to Kituyi.

‘‘Let me confess a certain history about Mwai Kibaki and myself,’’ Kituyi says when I later ask him whether it is true that before the 2007 general election, he was contemplating succeeding Mwai Kibaki come 2013, and that Kibaki was seriously entertaining the idea. Other than being one of Kibaki’s outstanding ministers, Kituyi had become the founding chairman of NARC Kenya, a new energized political party on which a faltering Kibaki was to ostensibly seek reelection.

‘‘Sometime in the year 2000, I received a phone call from Mwai Kibaki who asked me whether I passed through Nakuru often,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘I told him I did, and Kibaki asked me whether I’d be passing through Nakuru that Friday. I said I would. He asked me to meet him at Stem Hotel at 7.30am.’’ Kibaki was the leader of the Official Opposition, Kituyi the opposition’s Chief Whip.

That Friday, Kituyi left Nairobi in the wee hours of the morning. ‘‘The roads were terrible those days,’’ Kituyi says. On arriving in Nakuru, Kituyi found Kibaki waiting, and after exchanging pleasantries, Kibaki asked Kituyi to drive behind him. Kituyi followed Kibaki, until they arrived at Kibaki’s farm near the Menengai Crater, overlooking Nakuru. Once at the farm, Kibaki told Kituyi he had wanted Kituyi to get there early before the animals were released to go out to pasture.

‘‘In Kikuyu custom,’’ Kibaki told Kituyi, ‘‘when an elder gets to my age (69), you look at your children and pick one of them and say, I have a sense that one day you will be able to keep my family together, and you give him a heifer, to say go and nature this heifer, so that one day my grandchildren can have milk, and one day you might slaughter a goat for me and fellow elders.’’

That day, Kituyi says, Kibaki gifted him four pedigree heifers in calf, four dorpers and four goats. ‘‘The symbolism of that moment wasn’t lost to me,’’ Kituyi says. On election day in 2002, one of the heifers gave birth as Kibaki was voted in as president.

The second allegorical incident happened five years later.

‘‘In the year 2005,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘African ambassadors in Geneva and African ministers of Trade requested me to be the African candidate for director general of the World Trade Organization.’’ At the time, Kituyi was Minister for Trade, showing great promise on the international stage.

‘‘I went to see Mwai Kibaki,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘and Kibaki told me, ‘‘Kituyi, you may not know but your personal history is very similar to mine. In 1960, I left my station as a lecturer at Makerere University and volunteered to be the Executive Officer of KANU. I wrote its manifesto, gave it a national agenda, and helped it create a credible government infrastructure for the Kenyatta years. Then in 1969, I was offered to be Vice President of the World Bank.’’’’

Kituyi had been founding Executive Director of FORD in 1992, thus the comparison.

When Kibaki went to see Jomo Kenyatta, Kenyatta had some words for him.

‘‘I want you to understand that you have been very important to my government,’’ Jomo Kenyatta told Kibaki, his 35 year old Minister for Commerce. ‘‘Look at your colleagues… there are certain things I can only do through you. I have not given you the biggest job, but I have trusted you. I don’t look over your shoulder all the time. Usually in politics, you give the big jobs to people you don’t trust so that you get to see what menace they are up to. I know the World Bank can find another Mwai Kibaki, but I cannot find another Mwai Kibaki for my cabinet.’’

After this narration, Kibaki had a question for Kituyi.

‘‘Does this ring a bell for you?’’ Kibaki asked his 49 year old Minister for Trade. ‘‘Do you recall our meeting at my farm in Nakuru? I need you more than the World Trade Organization needs you. One day you may serve the world, but for now your country needs you.’’

‘’I had that conversation with Mwai Kibaki,’’ Kituyi reiterates in a near whisper.

There was one witness to the above exchange, and Kituyi suspects that the person leaked the conversation ‘‘to our political friends,’’ as Kituyi calls them, since immediately from that point onwards, Kituyi became targeted by some of his colleagues within the Kibaki political machine.

First, his leadership of NARC Kenya was curtailed by the introduction of a rotating chairmanship, before Musikari Kombo and Simeon Nyachae gave Kibaki a softly delivered ultimatum – they wouldn’t fold their respective political parties to support Kituyi’s NARC Kenya experiment, and if Kibaki insisted on going the Kituyi way, then they wouldn’t guarantee him votes in their regions. Unless he came through FORD Kenya – of which Kombo had defeated Kituyi to become leader – Bungoma would be hostile, Kombo told Kibaki. Cornered, Kibaki opted to set up and run on the Party of National Unity, supported by a number of constituent parties, including FORD Kenya.

Left to his own devices five months to the 2007 general election, and being keen on not going back to FORD Kenya, Kituyi’s last minute recalibration cost him his parliamentary seat. To him, his walking away from FORD Kenya wasn’t taken well by his constituents. The Bukusu still held the party as the embodiment of their communal aspirations for ascending to state power. Kituyi dusted off his resume, and quickly found a home at the Brookings Institute in Washington, D.C.

*

When Mwai Kibaki took office in January 2003, Mukhisa Kituyi and others who’d spent all their years of active politics either as pro-democracy activists or as firebrand opposition MPs had to acclimatize to their new reality as government ministers. For Kituyi, the demand to make the transition was instantaneous. Before being sworn in as minister, Kituyi received documents to read in preparation for a ministerial meeting on AGOA happening in Port Louis. And just after he lifted his right arm and made an affirmation – as a Quaker Kituyi doesn’t swear – Kituyi took off.

“On the day I arrived back into the country from Mauritius,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘I found workers at the Export Processing Zone had gone on strike and there was serious destruction of property.’’ The new minister instructed his driver not to take him home, but to instead drive straight to Athi River, where Kituyi would speak to the workers. ‘‘They had imagined their woes were because of the Moi government, and now that there was a new government, they wanted better,’’ Kituyi says. On arriving at Athi River, stones and molotov cocktails were briefly laid on the ground as workers cheered, with one of them asking comrade Kituyi to first sing for them, for starters.

‘‘To them, I was still Kituyi the activist,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘not Kituyi the government minister.’’

Then the compromises of running government followed.

‘‘During the first cabinet meeting,’’ Kituyi says of yet another reality check, ‘‘Kibaki asked us to donate Kabarnet Gardens to Moi. Usually, if you are vindictive you would say these people have stolen from us, we should stop them from stealing more. But we took the premier property Moi had occupied for more than 30 years and donated it to him as a gift. It was an important signal.’’

Kituyi was toning down, learning the difference between theory and practice.

Kituyi goes on to list an array of early-day interventions made by the Kibaki government – setting up of the National Economic and Social Council (NESC), the buying back of (instead of seizing) strategic assets from allies of the previous regime, the growth of the economy from a paltry 1.1%, and the list goes on. However, to Kituyi, three things happened and it was all a sad downward spiral.

‘‘The first setback was that President Kibaki had a stroke early in his reign,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘and certain forces around him panicked and saw an opportunity for self enrichment.’’ This is where Anglo Leasing and other scandals rained. Then there was the 2005 referendum. ‘‘It was totally political stupidity,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘Some of my colleagues in government got too full of themselves and thought since we are in government we can always get whatever we want. The arrogance of going to a referendum that was totally unnecessary broke the spine of the Kibaki government.’’

And then there were the Artur brothers, and the raid at the Standard Group.

‘‘Around the same time government threw away political capital on a very stupid thing,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘the Margaryan and Sargasyan mercenaries from eastern Europe saga, total abuse of office. Again hubris. You are drunk with power and get carried away in delusions of grandeur.’’

‘‘These events resulted in a poor exchange rate between economics and politics,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘so that our good work was not being positioned to be the basis for legitimate reelection.’’

But it wasn’t all gloom. For Kituyi, aside from applying more of his technocratic side and taming his rabble rousing elements, becoming minister did something else to him. ‘‘More than I had ever thought of and grasped intellectually,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘I came to see what the government can do. Government controls 70% of the economy, and has the capacity to allocate poverty and to allocate wealth. That became very clear to me.’’ This realization informed Kituyi’s ambitiousness as minister, aware that he needed to establish sound policy and match it with leadership as he reversed the damage done during ‘‘the Biwott years,’’ in reference to his predecessor’s reign.

Of his long list of achievements, Kituyi singles out the scrapping of 34 business licences, which he says had made doing business cumbersome and set the stage for corruption at all levels.

‘‘Being minister demonstrated to me in a way that I have only confirmed through my intellectual and fiscal sojourn of what is possible if you have a leadership that has a clear idea of where it wants to go,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘so when I tell people I know how to make Kenya’s trade work and know how to make Kenya an investment destination, I know because I have experienced it in practice as minister and as someone who’s interacted with governments which have done it.’’

*

The first time United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon headhunted Mukhisa Kituyi for a high ranking job as one of the UN Under Secretaries was in 2011. A vacancy for Executive Secretary had arisen at the Addis Ababa based United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). To root for Kituyi through official channels, Moon’s office called the office of Kenya’s Permanent Representative to the UN in New York, and requested the ambassador to reach out to the relevant authorities and activate Kituyi’s nomination as Kenya’s candidate for the UN job.

If Ban Ki Moon knew what was to follow, his office wouldn’t have made that call.

‘‘When the message got to the Kenyan ambassador in New York, the ambassador called the head of public service in Nairobi and informed him of the vacancy at UNECA,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘but instead of asking the head of public service to nominate Kituyi, the ambassador instead asked that he be presented as Kenya’s candidate for the job. The head of public service obliged.’’

In the meantime, Ban Ki Moon’s office was still looking out for Kituyi’s name as Kenya’s nominee, but when this wasn’t materializing, Moon’s office made a second call to the office of Kenya’s Permanent Representative to the UN, and asked to speak to Dr. Josephine Ojiambo, Kenya’s Deputy Permanent Representative to the UN. ‘‘Dr. Ojiambo was asked why Kituyi’s name had not been presented for the UNECA job,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘and unaware that her boss in New York had in fact nominated himself, Ojiambo called the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and relayed the information. The PS wrote a letter nominating me.’’

At the time, Kituyi was briefly based in Addis Ababa, consulting for the African Union on the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). And so when the summit of African heads of government met in Addis to elect the UNECA Executive Secretary, Kituyi was in the vicinity.

‘‘On the sidelines of the summit,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘the PS for Foreign Affairs whispered to President Kibaki that he should canvas for me among fellow heads of state in support of my candidature. But when the PS said this, President Kibaki’s Private Secretary bent over and told Kibaki in Kikuyu, ‘‘Don’t canvas for Kituyi. We have one of our own.’’ President Kibaki fumed, telling him, ‘‘Don’t speak to me in Kikuyu when I have non-Kikuyu ministers. Why are you telling me we have one of our own? Isn’t Kituyi ours?’’’’ Kituyi says he has alibis in the persons of two former cabinet ministers, Moses Wetangula and Dalmas Otieno, who were present as this transpired.

After the Addis debacle, Kituyi received a call from Ban Ki Moon’s office informing him of their embarrassment at Kenya presenting two candidates for the UNECA job. Moon’s office confessed that they considered the matter internal competition between two Kenyans, and opted to stay out of it. They asked Kituyi if they could withdraw his name, and consider him for a future position. That position arose less than two years later, and this time no ambassador was called.

Kituyi had not applied to be the Secretary General of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), but after the first round of recruitment was complete – it was the turn of an African to lead the UN agency, a group of 69 eminent Africans, including Koffi Annan, wrote an open letter decrying the calibre of shortlisted candidates for the job. Some African governments and heads of state joined in the chorus. As a result, Ban Ki Moon canceled the process and set up a headhunting team, tasked to bring him four names of Africans who had the credentials and firepower for the job. Kituyi’s name was on top of the list, and after being grilled by the panel, Kituyi had a one hour session with Ban Ki Moon. The job was as good as Kituyi’s save for ratification through a vote by member states, who voted for him unanimously, twice.

‘‘In the final stage of being picked to lead UNCTAD,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘the UN Secretary General called me and said, ‘‘It is important to inform your President that you as his citizen is being appointed to such a position.’’ That’s when President Uhuru Kenyatta was informed. Otherwise the Kenyan government had played absolutely no role in my nomination whatsoever.’’

This is how Kituyi became Kenya’s highest ranking international civil servant for 8 years, during which time he held two cabinet retreats between UNCTAD and President Uhuru Kenyatta’s government, training ministers to better deliver on the government’s development obligations. Then there was that time when Kituyi brought in Chinese billionaire Jack Ma to support youthful enterprise, but largely Kituyi’s international role had little to do with Kenya and more to do with how Kenya and the rest of the community of nations worked together to spur growth.

And then Kituyi resigned and returned home to officially launch his rumoured presidential bid.

From the time Kituyi arrived back in Kenya until now, his routine – at least what is publicly available – has been to reconnect with elements of the Young Turks – like Raila Odinga with whom Kituyi has had several lunches – and those who weren’t part of the group but who were fellow travellers during the second liberation, such as Martha Karua, Kivutha Kibwana and Willy Mutunga. I ask Kituyi whether he is trying to reincarnate 1992 through these loose formations.

‘‘I was about 10 years younger than most of the Young Turks, and the Young Turks phenomenon is from 30 years ago,’’ Kituyi says. ‘‘So a lot of those Young Turks today are my age plus 10 years, and you cannot reconstitute them as a team to win power. What it means is that while saying we look for each other as people who have travelled in a certain direction together, we have to open up space for new leadership to join us. We cannot own this process.’’

However, Kituyi says the mechanics of opening up the space have been humbling.

‘‘I was 22 years old when I was expelled from the University of Nairobi for speaking truth to power,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘but today you meet 35 year olds who are sitting back and blaming the government and politicians for everything, instead of standing up to be counted as political actors. The second dilemma is that Kenyans are used to being organized around parties which peg their existence on ethnicity, where an older male is speaking to the rest of the country.’’

And so Kituyi is spending sleepless nights trying to create a new canvas for Kenyans to project their dreams, where political participation will not be limited to voting and supporting regional kingpins but go deeper to encompass the connection of everyday life to policy and leadership.

‘‘It is a frustrating yet rewarding phase in movement building,’’ Kituyi says.

And yet Kituyi is not living in his own little Utopia.

‘‘I am painfully aware that you cannot win power in Kenya as a lone ranger, and that people want to see an ethnic base behind you for them to take you seriously nationally,’’ Kituyi says. “So even if you’ve been mobilizing people who share a history with you, you need more than that. We will be offering Kenyans an option in leadership which is not just the traditional settling of scores between people who have fought each other before. This is where we are right now.’’

Kituyi’s last word? Two words.

First, if he becomes president, Kituyi’s first move shall be to reinstate the National Economic and Social Council (NESC), which he shall anchor in law so that no future president can scrap it. You need a roadmap, Kituyi says, otherwise you’re going nowhere. Secondly for Kituyi, all this talk shall be cheap if corruption persists. Luckily for Kituyi, he says, he has many weaknesses but corruption isn’t one of them. Kituyi proposes slaying the monster without being vindictive – so that those exiting from state leadership don’t feel targeted, a lesson Kituyi learnt from Kibaki.

I ask Josiah Omotto, Kituyi university classmate and comrade, who Kituyi really is.

‘‘Mukhisa is a bridge builder,’’ Omotto says. ‘‘When he was a Member of Parliament, I regularly went for a drink in Parliament and we used to rub shoulders with politicians from across the aisle. That’s how I first met the Total Man (Nicholas Biwott) and many others for the first time. If he becomes president, Kenya will migrate from a kakistocracy to a meritocracy. Mukhisa surrounds himself with think-tanks (both a strength and a weakness), and suffers no fools.’’

And being the good politician that he is, Kituyi has a final-final word.

‘‘There is a constituency that is about how we can think of transforming Kenya so that we can rebuild and have an even better Kenya post-Covid, because the transition is not about the election next August but about an agenda for national renewal, ’’ Kituyi says of those he seems to excite, ‘‘but that constituency is not an electoral majority and so you want to speak to other people. And by speaking to other people it doesn’t mean I agree with them. Some you may agree with, others you may leave by the wayside, others may lead you to other people.’’

Watch this space, Kituyi seems to say. There will be movement from the ongoing motion.

‘‘As Kivutha Kibwana puts it,’’ Kituyi says, ‘‘Tungali tunatafutana.’’

…

This project is a collaboration between

Debunk Media and the Star Newspaper.