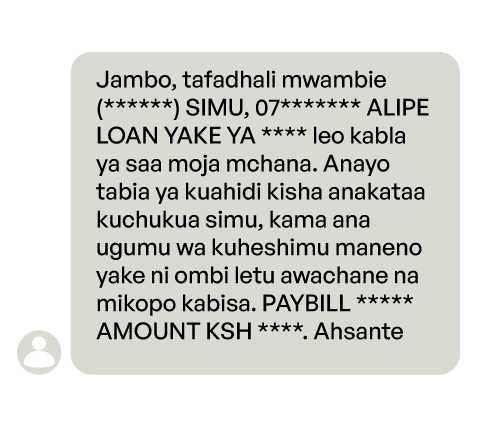

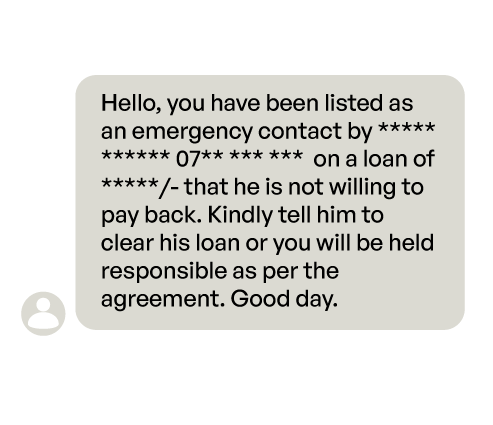

We all know someone, of someone, or we are that someone who has been on the receiving end of the wrath of angry mobile loan debt recovery agents. In the recent weeks, I have been that someone, bombarded with calls and text messages from agents incessantly nagging me to have someone on my contact list pay off their overdue loan.

For the uninitiated, the script goes something like this. It all starts with a simple message, then comes a call, then two and some. And if you block them, they simply switch numbers and like clockwork, call again. They never stop and never give up. Finally, it escalates to threats of you being held culpable for the loan, including being listed on the Credit Reference Bureau (CRB). Interestingly, my encounter comes post Central Bank of Kenya’s crackdown on Digital Credit Providers (DCP).

Here is why it’s all interesting.

In December 2021, former President Uhuru Kenyatta signed into law the Central Bank of Kenya Amendment Act of 2021, giving life to the Central Bank of Kenya (Digital Credit Providers) Regulations 2022. The regulations conferred the CBK with powers to not only ensure lenders are at the least, humane in their debt collection approaches, but to also regulate the digital lending services sector — which has remained unchecked for the longest time.

The DCP Regulations set out the licensing procedure and compliance requirements for Digital Credit Providers, which included data protection in line with the data protection act of 2019. Infact, a prerequisite for DCPs, both existing and new, which had until 17 September 2022 to submit their applications for licensing, was to first register with the Office of Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC). As it has been, when users install loan apps, the apps collect borrowers’ phone data, including contacts, messages and history of their mobile money transactions which lenders have been known to use to recover loans disbursed (as was in my case and many others in lenders debt shaming pursuits) and in some cases share the data with third parties.

By D-day in September, CBK had received 288 applications from interested lenders and has to date only listed ten approved lenders on its Directory of Licensed Digital Credit Providers. However, lenders way beyond the enumerated ten are still operational.

Enter Google Play Store.

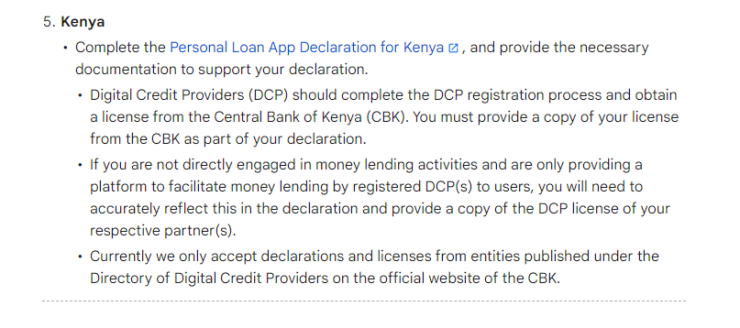

On 16 November 2022, Google updated its Developer Program Policy specifically touching on its financial related services. Under the updated terms, all apps on Google Play Store offering loans directly, serving as lead generators, and those who connect consumers with third-party lenders in Kenya (as well as India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Nigeria) have until 31 January 2023 to obtain and share with Google a copy of the DCP licence from their respective regulators. Failing to comply means the apps will be kicked out of Play Store.

Add to this, apps cannot charge an Annual Percentage Rate (APR) — the total interest rate charged on a loan plus other miscellaneous fees that is 36% or higher (that is the benchmark for all personal loan apps in the United States, home to Google). Some lenders operating in Kenya have been known to charge exorbitant interest rates, even way above the 36%.

With the new DCP regulations, lenders are required to disclose the total charges and fees for loans, interest rates, late payment and rollover fees, and the date on which the amount of credit and all interest, charges or fees are due and payable, before disbursing loans to customers.

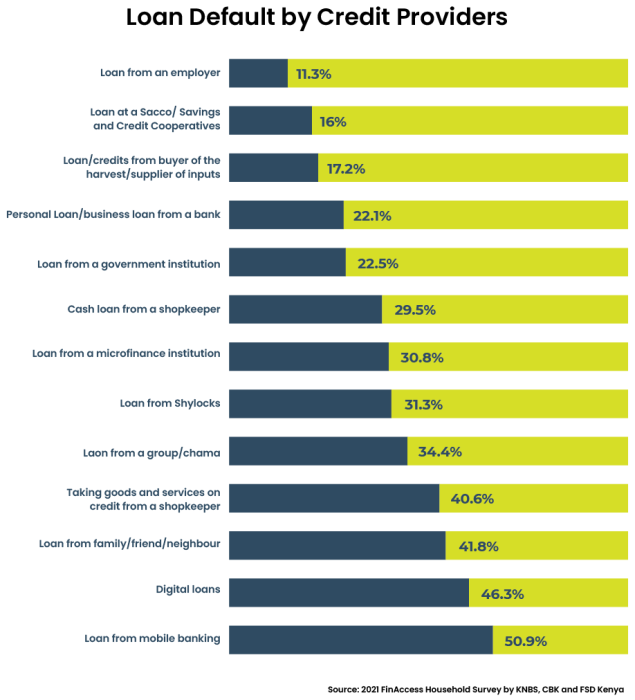

And when customers default on loans, creditors are bound by the In Duplum rule in its recoveries of monies owed. This means that creditors cannot collect interest that exceeds the principal owed, and any expenses incurred in recovering amounts owed should be reasonable. In the FinAccess Household Survey of 2021 by the CBK, FSD Kenya and the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), mobile lending platforms attracted the highest number of loan defaulters. Furthermore, creditors cannot use threats, or violence to physically harm the person, or their reputation or property, use obscene or profane language, make unauthorised or unsolicited calls or messages to a customer’s contacts.

Since the first mobile loans were issued by Safaricom powered M-Shwari in 2012, mobile-based lending has grown ten fold. By 2019, borrowers tapping into the digital credit systems had grown from 200,000 in 2016 to more than two million. Conversely, so have the lenders. According to the state of digital lending report by the Digital Lenders Association in Kenya (DALK) published in August 2021, more than 60 percent of Kenyans have digital platforms as their first choice for credit. Understandably so.

Digital platforms have led to easier and far more efficient access to financial services for consumers, especially for those with previous challenges to accessing credit from formal banking institutions. However, the free market reign resulted in regulatory lacunae. Before the CBK Act of 2021 was passed, digital lenders were neither recognised as financial institutions under the Central Bank of Kenya Act, Banking Act nor the MicroFinance Act. A consequence of the regulatory blind spots was that some businesses operated on models that have been predatory and exploitative.

It is expected that any disruption that heralds transformation and revolution is always a boon and a bane. But groundbreaking as loan apps have been, they have ensnared Kenyans in a cycle of borrowing at inflated rates. The vast majority of customers fall into debt traps by drawing loans to repay existing loans — a robbing Peter to pay Paul scenario. From the finAccess survey, 29.6 percent of the respondents admitted to having taken new loans to furnish existing ones. Therefore, it is imperative that the players are regulated. This may not solve the growing debt problem in the country, but may spare many from credit damnation by CRBs. And Google is here to make sure this happens.