In the last few months, the Kenyan news media has been awash with stories of a spate of school unrest, and the numbers are not promising – over 120 schools suffered some form of disturbance mainly happening in the last half of 2021. With such episodes recurring every few years, it is clear that not enough has been done to end the cycle. Has the country really learnt from the past incidents?

I

The first-ever known school protest in Kenya happened at Maseno School in 1908, two years after the institution was established by missionaries to educate sons of African chiefs. The students’ grievance was that Africans were receiving a raw deal by being subjected to a purely technical education – preparing them to be handymen for the settler colonialists, while Europeans received a more academic training, readying them for administrative roles.

Decades later, a cluster of post-independence school protests was recorded – 567 in total, happening between 1986 and 1991 – a piece of history rendered in Prof. B. A. Ogot’s My Footprints on the Sands of Time.

It was in July 1991, the final year in Prof. Ogot’s recorded cluster, that things took a turn for the worst. Male students at St. Kizito Mixed Secondary School in Meru attacked female students, set their dormitory on fire, raped over 70 girls and killed another 19. This criminal and devastating series of events shook the country to its core, resulting in President Daniel arap Moi establishing the Presidential Committee of 1991 on Student Unrest and Indiscipline in Kenyan Schools (Lawrence Sagini Task Force). It was chaired by Lawrence Sagini, a renowned educationist and first African minister for education in pre-independence Kenya.

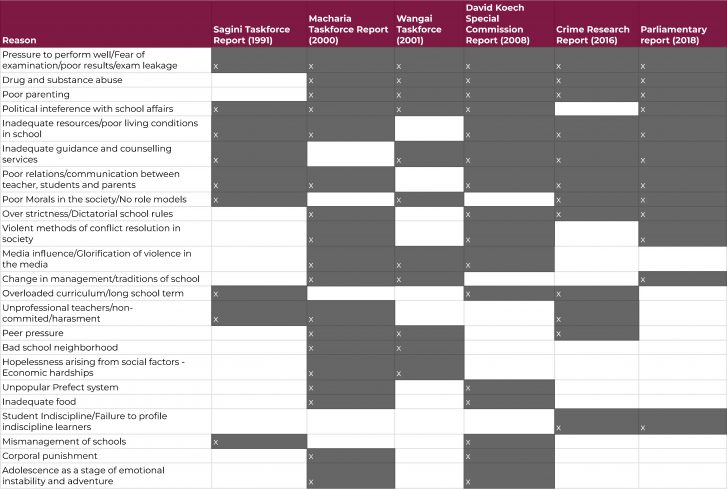

The Lawrence Sagini Task Force findings listed the causes of student unrest to include, among other things: lack of role models; overloaded school curriculum; communication breakdown between the students and the administration; mismanagement of schools; unprofessional teachers; inadequate guidance and counseling services; political interference with school affairs; negative impact of western values on the African traditional values; inadequate learning facilities; lack of adequate welfare services and poor performance in national examinations.

II

Years later in 1998, 26 students at Bombolulu Girls Secondary School died in a dormitory fire suspected to be an act of arson by fellow students. A year later came the 1999 Nyeri High School arson – students killed four prefects by locking them up in their cubicle and setting it ablaze. Around this time, numerous schools particularly in the former Central Province suffered disruptions. Following these events, The Macharia Taskforce was put together to inquire into the rising cases of school insurgency.

The Macharia Taskforce identified a set of factors leading to student unrest, including some of those which had previously been deduced by the Sagini Taskforce. The newer recommendations included inadequate quantity or quality of food; change of school traditions; drug abuse; the prefect factor; school administrative styles; corporal punishment; forced repetition; peer pressure; adolescence as a stage of emotional instability and adventure; proximity to slums; the negative influence of the mass media; undue political interference; national culture of violence; the changing society; economic and social hardships and poor parenting.

III

Then in 2001 The Worst Case of School Arson happened when a fire set by students at Kyanguli Secondary School in Machakos killed 67 students. This tragedy prompted the formation of the Task Force on Student Indiscipline and Unrest (The Wangai Task Force). It was chaired by Naomy Wangai, the then director for education.

The Wangai Task Force enumerated the causes of student agitation, its report reading like a replica of the previous two reports (Sagini Taskforce Report and Macharia Task Force Report) except for a few new findings which included: insecurity within and outside the school; devil worship permeating into schools and increased human rights awareness – students understanding the need to fight for their fundamental rights. The report from the Task Force emphasized strengthening guidance and counseling as an intervention of dealing with indiscipline in schools.

IV

Another wave of student outburst visited the schools in 2008 – the year that Kenya saw it’s worst post-election chaos. It would also be the year the country saw the highest number of school protests ever recorded in a year – more than 800 schools suffered strikes, according to Kenya Secondary School Heads Association (KSSHA). In response to the widespread unrest, the National Assembly set in motion the Special Commission to Investigate the Cause of School Unrest and Violence (David Koech Commission).

The David Koech Commission, as you might by now suspect, brought already familiar recommendations from previous inquiries into school unruliness, except that this was the first time the country heard of mobile phones usage by students being a factor.

By now it is an evolving problem, in that, new factors keep coming up with each subsequent report. The report gave other causes such as: the outlawing of caning in schools; an autocratic prefect system and the 2008 post-election violence. This episode of 2008 caused a shift in education policy – the then Minister for Education Prof. Ongeri, banned holiday tuition in an effort to relieve the students extreme academic pressure.

The country enjoyed a period of relative calm, but in the second term of 2016, hell broke loose again. About 130 schools were burned by students, according to the National Crime Research Center.

V

The National Crime Research Center went on a quest to establish the specific factors responsible for the recurrence of burning of secondary schools in the second term. The center polled both teachers and students on what they thought were the causes, and Voila! They were mostly the same old reasons.

Peer pressure was ranked highest by both students and teachers with 27.9% of students and 34.7% of teachers saying it was a contributing factor. There was however a new dimension this study introduced; strict reforms by the Cabinet Secretary for education, Dr. Fred Matiangi. The CS had taken an unprecedented decision to ban visiting and prayer days for form four students during third term as a measure to curb rampant exam cheating. 23% of the students and 18% of teachers cited the tough policy reforms as a contributing factor.

The study recommended the strengthening of guidance and counseling in schools by deploying full time and adequate professional counseling specialists to all schools. The other recommendations were: easing the burden of exams on students and decongesting the overloaded second term. It also called for profiling of Indiscipline cases across schools and adopting a more consultative decision-making processes in schools.

Players in the education sector were all too familiar with these recommendations, at least if the prior reports reached their desks. The question was, were any of these recommendations ever followed through? Not to satisfaction. That’s the answer we got from parliament in 2018.

VI

The Parliamentary Committee on Education and Research carried out another inquiry in 2018. A wave of unrest had visited the schools and more than 60 schools had been torched in the month of July. On top of the reasons that had been piling up over the years, the report raised the issue of sabotage from aggrieved teachers and corrupt principals who swindled schools resources causing discontent.

The committee recommended school heads to be holding consultative barazas with students and new school leaders be given training on school governance.

The reports are not short of reasons for school disturbances but one interesting trend is that certain reasons keep coming up report after report for over 30 years now.