If Dr. Alfred Mutua was to reincarnate after this lifetime, he’d probably come back as an American since he holds few things dear like he does the American dream, embellished with Australian and United Arab Emirates sensibilities. For the Machakos governor, not only is anything possible, but when that particular anything is made to happen, it should be made to happen with as much pomp and colour. It is a fast world mentality, Mutua posits, where things move fast. And now he feels Kenya, just like Machakos, needs to play catch up by moving chap chap to level up to the West. It is why he built the largest office block occupied by a Kenyan governor, and why he isn’t modest about it, like when President Uhuru Kenyatta visited the property, looked around and asked, ‘‘Is there another like this in Kenya?’’ And Mutua answered, ‘‘Yes, at State House.’’ Mutua may not want to build a new State House, but were he to become President, his mantra is simple. Nothing waits. Everything has to move chap chap, like in America and Dubai.

Part 1: From Makina to the World

Dr. Alfred Mutua’s welcome-to-America moment was one of him getting scammed by a New York cab driver. As a Form Five student at Jamhuri High School in Nairobi in 1988, Mutua had remained loyal to his Riruta Satellite Baptist Church, from where a group of American missionaries who used him as a translator identified him as someone they’d want to assist pursue further education. And so once the missionaries were back in the United States, they wrote Mutua a letter informing him they’d found a suitable college for him to study journalism, as well as secured a scholarship for him. All Mutua had to do was clear his A Levels, buy an air ticket and make his way to the United States.

And so upon completion of his A Levels in 1989, Mutua embarked on finding ways to ready himself for America. But being the pauper that he was, it took Mutua a whole year to get his act together, culminating in what he calls a poor man’s harambee for the air ticket, which yielded 12,000 bob of the required 25,000 shillings. Luckily for Mutua, a good samaritan named Kavua wa Kathuku who worked for a travel agency in town heard of Mutua’s predicament and reached out to his employers, who donated air miles to Mutua, so that combined with whatever Mutua had raised, he could afford the ticket.

‘‘My father took me to Gikomba Market, where I bought mitumba shoes, trousers, an African prints shirt – I was told when you go to the West you must dress like an African, a jacket, underwear and socks,’’ Mutua says when we speak at the sprawling Machakos County headquarters, the infamous White House. ‘‘I was taking the mitumba clothes back to where they had come from, America, only that now they were on my body.’’

After buying the air ticket and the mitumba clothes, Mutua was left with $200.

‘‘On 11 August 1991, I left Kenya on the last Pan Am flight, a Frankfurt bound Airbus,’’ Mutua says. Pan American Airways, the American aviation behemoth, was just about to fold its operations. ‘‘Once at Frankfurt, we then took a Boeing 747 to New York City.

’’Mutua is huge on detail – dates and days, aircraft models, the whole shabang.

On that particular Nairobi-Frankfurt flight, Mutua happened upon Dorothy Malinga, a former classmate of his at Jamhuri (back in the day, the school’s A Level class was mixed), who was also America bound. During the flight, Mutua had flashbacks of when as a child he was once seated outside the wooden shack they called home in Riruta, with little outdoor structures made of sacks standing in for a toilet and bathroom. With Mutua was his maternal grandfather, who Mutua says he takes a lot after, especially his chap chap ways. An aeroplane was passing overhead, and so Mutua pointed at it and told his grandpa that he’d grow up to board an aircraft someday. His grandad agreed, telling him he’d board one and travel far.

And now here Mutua was, headed to the United States.

Much as he had never flown before, Mutua says he was pretty unfazed during the flight because ‘‘mimi nikilikuwa nimesoma.’’ Having learnt early that through flipping pages one could go anywhere in the globe and even do the impossible, like sleep with beauty queens, Mutua says he’d amassed ideas about the world from the books his mother and his late aunty Milka bought him – biographies, fiction, poetry – and he now had to put them into use. He couldn’t sleep for the entirety of the eight hour flight to Frankfurt.

‘‘I knew New York,’’ Mutua says with a straight face. ‘‘I knew the Brooklyn Bridge, I knew Harlem, I had watched videos of Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X. I knew Harlem! I had also watched tons of American comedy shows. I even knew places in New Jersey.’’

Mutua’s second-hand knowledge of America was about to prove useful and detrimental.

‘‘When we arrived in New York, my friend Dorothy was a bit flustered, and so I offered to take her to New Jersey, which is where she was going to start school,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘She had about five suitcases. I had one brown one. It was a Sunday, not a busy day. And so I asked someone how to get to Edison in New Jersey. The person told us to take a bus from the John F. Kennedy International Airport and alight at the Grand Central Station, from where to pick a train to New Jersey. Dorothy and I took the Manhattan bound bus.’’

On that bus ride, Mutua drove over one of his American landmarks, the Brooklyn Bridge, and so the man from Masii in Mwala Constituency knew he was in familiar territory. But after being dropped off by the bus, Mutua looked around and couldn’t see the Grand Central Station, or what his idea of it was from the books and movies he’d read and watched. Mutua decided that they had been dropped off at the wrong location, and so ‘‘because mimi najua mambo,’’ Mutua hailed a cab and asked the driver to drop them off at the Grand Central Station. The cab driver did his rounds and soon Mutua and Dorothy were at the train station. Mutua paid $11, leaving him with $189.

But on getting off the cab and pulling down their six suitcases, Mutua looked around, only to spot the corner where the bus had dropped them off, not too far away from where the cab had now brought them. All he had needed to do after alighting from the bus earlier on was to simply turn a corner, then he’d have seen the Grand Central Station. But because he thought he knew how to navigate America, taxi hailing and all, he had just offered the cab driver free dollars for a fake trip.

‘‘We had been conned,’’ Mutua says. He had officially arrived in real-world America.

But as if losing the $11 wasn’t enough, Mutua took the train to New Jersey with Dorothy, arrived there, realized she couldn’t get accommodation at her school that Sunday, and being the gentleman he’d read he needed to be, Mutua offered Dorothy some money to pay for a room at the holiday inn where she’d spend the night. Mutua then took a cab from New Jersey to John F. Kennedy, a ride that cost him $90. With less than $100 to his name, meaning he couldn’t afford a hotel room, Mutua passed out at the airport’s international lounge. To someone else, this may have been a catastrophic start to their stay in a foreign country. To Mutua, this was life as he knew it.

Growing up in Makina in Kibera, Alfred Mutua’s childhood was characterized by the mud house his family shared, an environment Mutua says was infested with rats and night runners – you’re mistaken if you thought this was a village phenomenon. But much as things looked gloomy, Mutua’s parents, who were low cadre civil servants, maintained some form of good cheer in the home. There was always hope that things would get better one way or another, if not for the parents then at least for Mutua and his sister.

‘‘One of my fondest childhood memories was when my dad brought home fish,’’ Mutua says of life in Makina. ‘‘To my family, eating fish was a whole event because my dad would bring a single tilapia which my mum would fry, then the whole family – myself, my sister Anne and my parents – would sit around the table and watch my father, who was a comedian, debone the fish bit by bit before he distributed the fillet to each one of us.’’

Mutua says other times the feast would get more meaningful when his dad brought home mbuta, the Nile Perch, which had thicker chunks of flesh. The family had fish say once a fortnight, but mostly Mutua says the family was vegan, not because of choice but out of circumstance. If not fish then Mutua’s present day favorite of matumbo sufficed. It was these simple pleasures that made an otherwise deprived life bearable.

It is while living in Makina that Mutua started school at Karanja Nursery School, before proceeding to Toi Primary School. As Mutua attended Toi, the family felt it had had enough of Kibera, opting instead for a wooden shack with an earthen floor in Riruta Satellite. The one thing this move did was it made Mutua a member of the Riruta Satellite Baptist Church, which is where the Americans discovered him. But even before the Americans, it was through a connection from that church that Mutua managed to pull through his O and A Levels, because his parents couldn’t afford to educate him.

‘‘I dropped out of Dagoretti High School when I was in form two in 1985,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘And so I went and got a mjengo job from the site of one of our church members, a man called Stephen Kirui. I would be given a wheelbarrow to fetch water for the fundis.’’

But even as this was happening, Mutua was keeping busy at the church, where he was an outstanding actor and Sunday school teacher. It was through watching Mutua’s roles in plays at the Baptist Church that yet another member of the church, Hezron Waithaka, who worked as an auditor, decided to pay Mutua’s school fees from that point onwards. Waithaka would send his driver with a cheque for Mutua every opening day until Mutua was done with his O Levels at Dagoretti High School and proceeded to the better performing Jamhuri High School for A Levels, where Mutua’s benefactor continued catering for his school fees. It is this school of hard knocks background that prepared Mutua for America.

And so after brushing aside his initial New York misadventures, Mutua settled in at Yellowstone Christian College in Billings, Montana, where he quickly realized it wouldn’t be the best fit for his journalistic pursuits. ‘‘Yellowstone College was more inclined towards training theologians, and I felt it didn’t cater for the sorts of aspirations I had,’’ Mutua says, as he boasts of how he doubled the Black population in the locale. There was only one other Black resident in the town in the middle of nowhere, Mutua says. Mutua bounced.

Mutua’s next stop was Spokane in Washington State. Considering a year had flown by at Yellowstone and he hadn’t made much academic headway, Mutua went for a bridging course at Spokane Community College, after which he was admitted to Wentworth University for a bachelor’s degree in journalism. At this point, Mutua was staying with a missionary family whose matriarch, Marie Jones, had become his adopted grandma.

But considering that Mutua had left behind his full scholarship at Yellowstone College, he was now only able to get a new scholarship catering for part of his tuition fees,meaning he needed to find a way to pay up for the rest of his fees and leave something for his everyday sustenance. It was at this juncture that Mutua was to discover a skill that would carry him for the rest of his life. It was also around this time that Mutua realized much as he was in America, he wasn’t in a position to support his parents back home.

‘‘My family got poorer while I was in America,’’ Mutua says. But still, Mutua persisted.

Part 2: Muthaura’s Shadow

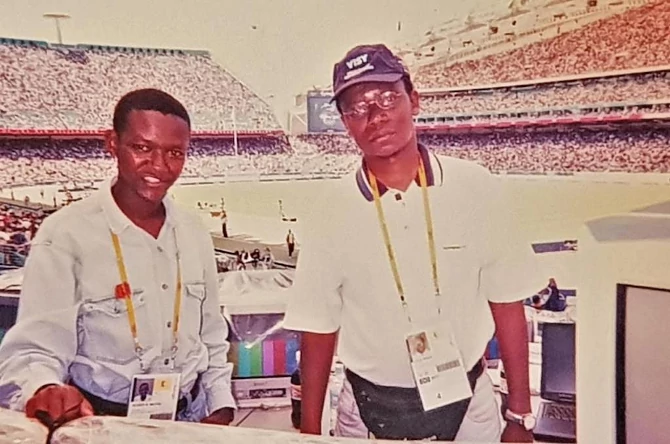

In the year 2002, Dr. Alfred Mutua was in the middle of one of his most adventurous journalistic assignments when he received a life changing email. During the 2000 Summer Olympics held in Sydney, Australia, Equatorial Guinea’s Eric Moussambani made history by being the slowest swimmer in the 100m freestyle, taking a whopping two hours to cross the finish line. Yet due to false starts by his two competitors, Moussambani won the heat and was christened Eric the Eel. Mutua was dispatched to Equatorial Guinea by an Australian TV station to go and interview The Eel.

After graduating from Wentworth University with a BA in Journalism, Mutua had earned a scholarship to the Easten Washington University, where he obtained an MSC in Communication, topping his class. Mutua then returned to Kenya in 1997 and took up a teaching job at Daystar University, where he was the youngest lecturer at 27. On the side, Mutua doubled as a correspondent for the Nation Media Group, where considering he was paid per article, he wrote features almost every other day of the week, earning more money than some full time scribes. Mutua needed all the money he could make.

‘‘When I came back from America, I found my family had moved from Riruta Satellite to an even worse place in Kangemi, and so I moved them back to a better place in Riruta,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘While in America, I had the choice to either study and stick to the limited permitted working hours, or work illegally and get deported, which wasn’t an option.’’

It was while teaching at Daystar and working at the Nation that Mutua received five PhD offers with funding; Indiana University, Illinois State University, Leeds University, the University of Sheffield and University of Western Sydney. Mutua picked the University of Western Sydney, on the basis that as a 15 year old at Dagoretti High School, one of his teachers, Z.G. Wanja alias Big Fish – Mutua says he was a bulky man, had travelled to Australia and come back with a 30 minute long tale of his exploits for the school. Mutua vowed that he too had to go to Australia. That’s how he still makes his decisions, quick.

While studying in America, Mutua had taught himself filmmaking online, since both his undergraduate and graduate degrees didn’t cover electronic media. But once in Sydney, Mutua went all out, including attending the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS). And from that point onwards, Mutua became a one man army, travelling to do projects either on self assigned missions or for the various TV stations he was working for as a stringer. Mutua set up the lights, operated the cameras and did the interviews.

‘‘I was one of the first people to interview Joseph Kabila when he became president of the Democratic Republic of Congo,’’ Mutua says, and goes on to share tales of how it was a common occurrence to be approached by women in Kinshasa, asking, ‘‘Uko na bibi? Hapana Kenya. Uko na bibi hapa?’’ And if one said no then they’d say, ‘‘Sasa kuanzia leo mimi ni bibi yako.’’ But beyond the possibility of one getting married the moment they land in DR Congo, Mutua has nothing but praise for the city of rhumba.

It was under these circumstances – of moving all over Africa and elsewhere, like that time before New Year’s in the year 2000 (the turn of the millennium) when Mutua travelled by road from Nairobi to Harare making a documentary – that Mutua found himself in Equatorial Guinea in search of Eric Moussambani alias Eric the Eel. But after making the journey through Douala, Cameroon, and flying into Bioko island which hosts Malabo, Equatorial Guinea’s capital, Mutua couldn’t locate The Eel – who would later become his country’s swimming coach – because he had apparently travelled to Nigeria.

‘‘One evening I was coming from shooting a soccer game, and when I got back to my hotel room in Malabo, Don Roberto, the hotel security guard didn’t receive me with the usual excitement I had come to expect from him,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘When I got to my room, I found the door open with two suited men with shades seated on my bed watching the TV. The room looked ransacked. They asked me to pack my bag and accompany them, and didn’t entertain any queries. I was sandwiched at the back of a Mercedes Benz which drove on the main highway towards the airport. I knew I was being deported.’’

The Mercedes Benz stopped at a highly fortified compound. Mutua was asked to step out of the car and strip naked. He obliged. He was then asked to dress up and pick up his camera. Once inside the compound, Mutua was led to a tennis court at the back of what he says was a resplendent mansion, where he found an old African man and an Asian man exchanging groundstrokes. The Asian man was faring badly. After they were done playing, the old African man came at Mutua cheerfully. That man was Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, Equatorial Guinea’s President for Life. Obiang’s people had caught wind of the African journalist working for the Western press, and wanted their man to receive some coverage. Mutua was relieved. At least he wasn’t being deported.

It was after this incident that Mutua checked his email and found an invitation to go and teach Communication in the United Arab Emirates, an offer that was too good to resist. Mutua went back to Australia, wrapped up his PhD, bid goodbye to his employers and took off to Dubai, a vantage point from where the Kenyan government would spot him.

‘‘I visited Kenya in 2003 and passed by the Nation Media Group, where NTV was having hitches using a program called Final Cut Pro,’’ Mutua says. Wangethi Mwangi and Cyrille Nabutola were the incharges, and Mutua says he told them that whatever they were struggling with was what he was teaching in Dubai. ‘‘Wangethi Mwangi gave me a consultancy where I came to Kenya every month for 10 days. They’d put me up at The Stanley and pay me really well. I also got a writing slot in the Sunday Nation.’’

It was as Mutua was minting petrodollars as an assistant professor of Communication in Dubai and simultaneously munching the Nation’s shillings that he received a phone call from Rebecca Nabutola, who was the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Tourism.

Nabutola: Are you Alfred Mutua?

Mutua: Yes.

Nabutola: In that case please call this number.

Nabutola gave Mutua the phone number. Mutua called. The recipient was Raphael Tuju, the Minister for Tourism, Information and Communication. Tuju was at an event, and told Mutua to send him his Curriculum Vitae. A few months passed. Mutua didn’t hear back from the Minister or the PS. Then one Friday evening as Mutua was driving in Dubai, he received a call from the Office of the President inviting him for an interview slated for the following Monday at 8am. By this time Mutua had gotten wind that President Mwai Kibaki’s government was looking to establish the Office of the Government Spokesman.

Mutua’s next visit with the Nation Media Group was a week away, but seeing a chance to kill two birds with one stone, Mutua called the Nation and asked them to send him an air ticket, saying he wanted to conduct that month’s consultancy earlier than anticipated. The Nation sent their man the ticket. Mutua landed in Nairobi that weekend, only to find that across all the Sunday papers, the man being touted as the incoming Government Spokesman was the New York based Salim Lone, the one time subversive editor of the Sunday Post and later on Viva Magazine, who was a Communications Director at the United Nations. Lone knew the job was as good as his, and had resigned from the UN.

‘‘On Monday morning I went to the Nation Center, prepared my CV and other paperwork – I had written down ideas on what I would do as Government Spokesman,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘From there I went to the Office of the President, and was surprised when I saw interviewees arriving as late as 9am. Sitting there, I saw ministers streaming in, and at around 9.30am, an old man came and asked who had arrived first. The secretary said it was me. I was ushered into the interview room, where I found a number of ministers.’’

Mutua says he went in, did the interview – he was asked to converse in Kiswahili too – after which he drove to Masii to visit his grandma. As Mutua was driving back to Nairobi that Monday evening, his long-aerialed Sony Ericsson phone rang. It was Raphael Tuju calling. Mutua picked the call. Tuju informed him that he’d been hired as Government Spokesman, and asked him to report to the then Head of Civil Service Amb. Francis Muthaura first thing the following morning. ‘‘Tuju told me that after I had left the room,’’ Mutua flexes, ‘‘they wondered whether they needed to interview anyone else.’’

That Tuesday morning, Mutua went to see Amb. Francis Muthaura on the seventh floor of Harambee House as instructed. After getting the preliminaries out of the way, Amb. Muthaura told Mutua they’d send him an offer letter, asking when Mutua was ready to start. Mutua informed him that he couldn’t start immediately since he had students in Dubai and he needed at least three months to finish the semester with them, something which Mutua says Amb. Muthaura was greatly impressed by. ‘‘He was very happy,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘because he saw a man who wouldn’t simply walk out of a job because he got another. He told me to go and finish teaching the course. That they’d wait for me.’’

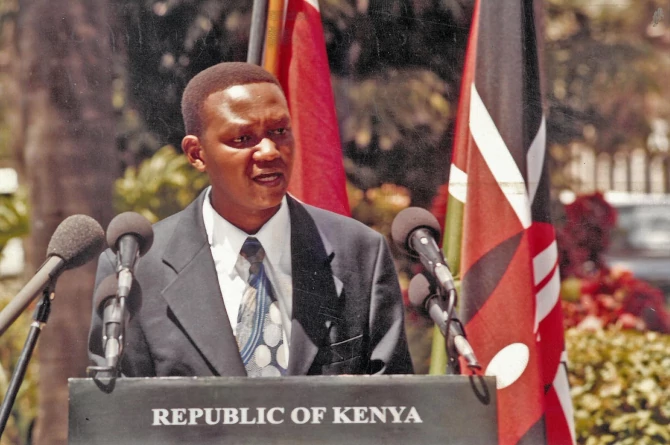

Mutua went back to Dubai, leaving Nairobi abuzz with speculation that the job was Salim Lone’s. In June 2004, Mutua jetted back into Nairobi ready to embark on his new assignment, and was put up at the Intercontinental by the exchequer. The following morning after Mutua’s arrival, he was picked up and taken to State House to meet President Mwai Kibaki. ‘‘Kibaki told me two things,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘Pick very good staff to work for you, and always speak the truth.’’ From State House, Mutua was chaperoned to Harambee House, where he was unveiled as Kenya’s first Government Spokesman.

And so began Mutua’s tenure as Amb. Francis Muthaura’s conspicuous shadow.

‘‘It took people by surprise when the announcement was made that I was the new Government Spokesman,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘and everyone started wondering who was this young boy? Senior editors and renowned journalists had all been bypassed, and so even I asked myself why me? I knew nobody. I had no godfather in government. ’’

Mutua was 33 years old.

‘‘I was thrown right into the fire because I came in at the time of Anglo Leasing, and there were some efforts at a cover up by some people, with John Githongo blowing the whistle,’’ Mutua says, but adds that he won’t spill the beans just yet because his tell-all autobiography is in the works and will be hitting the shelves soon. ‘‘I would speak and people within government would contradict me, because they weren’t used to the idea of having an official spokesman. But I kept going, and strictly took my briefs either from President Mwai Kibaki’s office or directly from Amb. Francis Muthaura.’’

And here, Mutua throws in a caveat, albeit belatedly.

‘‘I never made any personal statements,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘Everything I said had been discussed and approved, and so whether someone liked or disliked whatever I said, the fact remains that those were the statements sanctioned by government.’’

But as I speak to Mutua it becomes clear that he wasn’t just a mouthpiece or conveyor belt for what the big boys and girls in government wanted him to pass on to the public.

For starters, Mutua volunteers that he attended a sizeable number of daily briefings given to President Kibaki, in which instances Kibaki would show up and ask in that Mwai Kibaki-voice, ‘‘Haiya, dunia inasema nini?’’ It is an open secret that this was the purview of the National Intelligence Service (NIS), and in a different context Mutua submits that he and Michael Gichangi, the NIS Director General, had a cordial working relationship.

Aside from the highly classified briefings, Mutua shares that he was in the room when government was being formed or reshuffled, like in 2005 after ministers were fired for opposing the draft constitution, or in 2008 when a government of national unity was being put together. Mutua says he was the one taking minutes during such meetings, and that beyond just being a fly on the wall, he’d be given opportunities to share his thoughts. ‘‘I was a Kibaki insider,’’ seems to be what Mutua is saying, and none of this could have been possible had it not been for Amb. Francis Muthaura, who Mutua calls his mentor. ‘‘He’s one man who held this country together,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘and I learnt from him how a government should be run and how not to run a government.’’

It was while being Amb. Muthaura’s shadow, Mutua says, that he ended up drafting the earliest notes of what became Vision 2030. After a meeting of Permanent Secretaries who were being familiarized with Singapore’s practice of setting development targets in the form of visions, Mutua and Muthaura retreated to Harambee House where Muthaura asked Mutua to draft something. Mutua says he drafted what he termed Vision 2020, which he took to Muthaura, who made some changes before they took it to Kibaki, who made more changes before McKinsey & Company were roped in to design the full breadth of the project. ‘‘It is McKinsey who turned it into Vision 2030,’’ Mutua says.

Then there was the allocation of national projects, which Mutua speaks about as if it was the splitting of a goat among friends. Mutua says he wanted the proposed technocity to go to Machakos, Mua Hills to be specific, because he owned a farm nearby – he says this in that I-am-joking-but-I’m-not way he speaks sometimes. Mutahi Kagwe, the then Minister for Information and Communication, wanted the technopolis to be situated in present day Tatu City. Eventually, with the support of Muthaura, Mutua carried the day and the technopolis was taken to Machakos, first to Lukenya, but since the locals wouldn’t sell off their land, the city was transferred to Konza.

On his part, Mutua says Amb. Muthaura wanted the resort city to go to Isiolo, because it was closer to his rural home in Meru. But what was more dramatic was the night when Mutua had to go in search of a map at 3am in the morning, because they couldn’t agree on whether a port should be built in Lamu. Mutua says everyone in the room including President Kibaki wanted the port built at Dongo Kundu in Mombasa, but that it was Stanley Murage, the president’s special assistant, who argued for Lamu. Mutua brought the map, Murage made his viability case and everyone in the room was convinced.

This is how a country is run.

But then there’s Mutua’s fascination with Lucy Kibaki, the First Lady. By all indications, Mutua may not have had a godfather, but his reverence for the former First Lady shows just how much she liked having him at State House. First they started out with the First Lady asking Mutua to design a seating chart for all national celebrations, an assignment Mutua says he carried out with the assistance of the NIS Director General. Then there was the 2005 referendum, where Mutua says the First Lady called him to be in the room as she interrogated those who were leading the YES Campaign, telling them how they were siphoning resources out of the campaign while their opponents were riding to victory. ‘‘They tried to argue with her,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘but Mama Lucy told them she had her ears to the ground, telling them she was sure the government would lose 60% to 40%. It came to pass.’’ And yet what really stood out for Mutua was how the First Lady ran a tight ship at State House, never allowing the free flow of food and drinks since the President was on a super strict diet. To Mutua, this alone saved Mwai Kibaki’s life.

‘‘We’d have lunch with the President,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘and he’d have two drumsticks, a banana or an apple and water. That was it. No juice. No soda. No starch. This is what kept Kibaki alive, because were he to crave the steaks he was used to and so on, and were he to have them, then he’d have messed up his diet and possibly developed complications.’’

I ask Mutua what his lowest moment was as Government Spokesman.

‘‘I remember someone calling me while I was sitting with Police Commissioner Maj. Gen. Hussein Ali and Amb. Francis Muthaura,’’ Mutua says, referencing the 2007/2008 post election violence. Incidentally, Muthaura and Ali would initially be listed as suspects set to appear before the International Criminal Court at The Hague on grounds that they’d played a role in the violence, before they were let off the hook. ‘‘The person was crying on the line, telling me they were under attack somewhere in Naivasha. I told the Police Commissioner, who started making phone calls. But as this was happening, the person kept calling, saying the attackers were drawing closer, that they were killing people nearby. Eventually, the caller was killed. The police were not taking orders.’’

All said and done, Mutua says what kept him close to the center of power was his absolute loyalty to Kibaki and consistency on whatever they had agreed upon.

‘‘I am not a watermelon like some people in this country,’’ Mutua jibes.

Part 3: The Machakos West Wing

Dr. Alfred Mutua lost his scholarship when he left Yellowstone College – which was his first home when he landed in America – and moved to Wentworth University to study for a BA in Journalism. And so in his pursuit to find an alternate scholarship, Mutua auditioned for and was enlisted as a participant in forensic speech contests, where he practiced and participated in public speaking and debate. Through forensics, Mutua earned a new $14,000 scholarship, which sustained him during his undergraduate studies. But beyond just earning him the scholarship, Mutua credits forensics for paving the way for him to become Government Spokesman. It was predestination, he believes.

‘‘My wife told me that now that you’re in government, you can do all those things you’ve always wanted to do,’’ Mutua says. I ask Mutua what those things are. ‘‘I always wondered why we were so poor, why our infrastructure was so bad, why we had water problems,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘I kept on asking, these ministers had always come to the US, why can’t they fix things and change Kenya? I had a burning desire to fix Kenya the way I had seen it done in the US, Australia and other countries I visited.’’

After being Government Spokesman for almost a decade, Mutua sought real power.

‘‘We were having a meeting in Mombasa to discuss the draft constitution in 2010, and to my right was National Security Intelligence Service (NSIS) Director General Michael Gichangi, and to my left was Attorney General Amos Wako,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘When I read the section on devolution, I asked Gichangi, the governor is going to be the next most powerful person after the president, right? Gichangi said yes. I asked Wako the same question. Wako too said yes. It is in that sitting in Mombasa that I decided I was going to be the governor for Machakos, so that I can have power to do the things I had always wanted to do; bring water, build roads and stadia and bring Dubai to Machakos.’’

And so in September 2012, Mutua tendered his resignation. As a show of appreciation, President Mwai Kibaki asked Mutua to go and see him the following morning. ‘‘Kibaki gave me a briefcase and told me that that was his contribution and that of Lucy Kibaki,’’ Mutua says. Kibaki became Mutua’s first campaign donor. Mutua won’t say how much Kibaki gave him, but says it was in the millions. Then as the campaigns drew to a close, Mutua says he called on yet another president, Tanzania’s Jakaya Kikwete, who also gave him a briefcase which Mutua says he used for the final push, like paying agents.

‘‘I had learnt how to run a political campaign during Kibaki’s reelection bid in 2007,’’ Mutua says when I ask him how he navigated the electoral politics terrain as a first timer. ‘‘I got a call from Amb. Muthaura one Sunday morning, asking me to go to his office, where I found Raphael Tuju. It was in that meeting that the idea of a Party of National Unity was hatched by Tuju, and we then proceeded to send choppers to pick up party leaders who were out of town. By 4pm, we had all assembled at the KICC where I wrote Kibaki’s speech, inserting ‘Kazi Iendelee’ after every paragraph. We didn’t have branding material in any other colour save for blue, and that became the party colour. We thereafter set up the secretariat, and that’s where I learnt the ropes.’’

Mutua was elected governor at 43.

‘‘I came in with a concept of building a new city,’’ Mutua says of his early day masterplan for Machakos. ‘‘I took it to President Uhuru Kenyatta, who really liked it. I then did an investment conference and got commitments of up to 2.1 trillion shillings, which was going to finance the project. Unfortunately my political competitors feared that were the city to become a reality then I’d outshine them, and so they went to court and it took six years before the matter was thrown out. By this time investors had bolted. They are just starting to come back now, at the tail end of my term. Machakos missed out big time.’’

At the center of that city was the Machakos White House, the county’s seat of power which Mutua says cost 300 million shillings and took an average of six months to build. Surrounded by huge tracts of land, the all white office block is humongous, sitting on an acreage Mutua’s doesn’t recall off his head but one can visually estimate it to be about ten soccer fields if not more. When my colleague goes all the way to the property’s entrance, the optics make him appear not as small as an ant but gives you the effect that you could be looking at a human version of an ant – so tiny that you have a general idea that there’s a human there but you have nothing to work with in term of specifics.

Mutua occupies the entire building – it is the governor’s office, everyone else has their offices elsewhere, including his ministers – and takes the West Wing as his personal operations base. Here, there’s his huge ensuite office, there’s the open plan reception area, there’s an executive dining room, a kitchen, Mutua’s chief of staff’s office, and at least three huge lounges and a second dining room for guests. Mutua’s media team also sits on this side of the building. The other half of the building seems unoccupied.

‘‘When I became governor I refused to take up the office of the former mayor because a governor is not an elevated mayor,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘If you go to America, this is how a governor’s office looks. In building this office, I am entrenching devolution in Machakos.’’

Mutua gives me a tour of the building, its eight executive toilets, its huge corridors, its executive boardrooms, and every time we meet a staffer they almost freeze as they give way. The one thing that’s clear is that aside from all the reasons Mutua gives about the necessity of such a seat of power, it is also power play, a power arrangement, so that when one walks in they instantly start seeing him in a different light. Big man’s big office.

But beyond just size, Mutua has fetishes.

‘‘I am very clear about what I want and what I don’t want. I don’t like something called mathogothanio. I like things done well,’’ Mutua says when I tell him I have a sense he’s the one who picked the building’s curtains, going by how specific he is about everything. ‘‘I don’t like hanging wires, because wires hanging is a sign of a third world mentality. I like clean toilets, flowing water, because they bring efficiency. I learnt this from the Japanese. They recovered from being nuclear-bombed and became a world power by doing things properly, even if they are minimalists. I want good things for my people.’’

I notice something else. Mutua still keeps the staff he had as Government Spokesman.

‘‘I believe that you don’t leave your people behind,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘I believe that if you have trained your people you move up with them. My chief of staff, my drivers, my media liaison, my security detail and so on are the same ones I had as Government Spokesman. They understand my systems. I trust them. I know them. They are family.’’

When Mutua was growing up in Makina, Kibera, neighbours nicknamed him Jogoo for just how active he was. And when his father took him to report to Dagoretti High School in 1984 aged 13, fellow students wondered why a child had been brought in their midst. Mutua was super tiny. And yet when bullies attempted to make a go at him, Mutua exploded. Then one day while in form five at Jamhuri High School in 1988, a sister to a childhood friend told Mutua, ‘‘Please take care of your friend in future.’’ Mutua was confused. The friend’s sister told him he’d go places in life and shouldn’t forget her brother. And when Mutua was playing basketball at Yellowstone College in America, a teammate told Mutua he had fire burning in his chest, and that Mutua needed to be careful where he channeled that fire lest he burnt himself. And on and on.

Mutua shares these anecdotes in saying it is all foreordained. That this is how he will become president, because people have always seen it in him and told him as much, and when anyone has tried to overlook him for his size or such, he has always proved them wrong. This, tied to his fast and glittering ideology – Dubai, done at super speed.

‘‘If we move at the speed of America or Singapore, we can never catch up with them because they are already way ahead of us,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘The problem is that as it is, we are not even moving at the speed at which these countries are moving. We are much slower. And so to catch up with them we need to move at double their speed, so that if they take a day to process a passport, ours has to be done in six hours or less.’’

And how has he performed as a governor?

The achievements are too many to list off the cuff, but Mutua takes pride in how he’s improved infrastructure, how he’s rolled back the threat of hunger, and how he’s transformed the health sector. ‘‘Machakos is no longer a recipient of food aid,’’ Mutua says, ‘‘but when you look around everyone else is still on the relief food wagon.’’ The governor says he copy pasted a Malawian model where farms get ploughed for free and farmers are given free planting seeds, this and the fact the county bought borehole drilling equipment and has dug dozens of boreholes across Machakos. But the apple of Mutua’s eye is Machakos Level 5 Hospital, which he says is easily one of the cleanest if not the cleanest public health facility in the country. And now to bring these to Kenya.

‘‘I want to make it easy for people to exist in Kenya,’’ Mutua pitches. ‘‘I will remove all this bureaucracy and make it easy for people to do business. Today, there are 34 steps one has to undergo before a payment is made. All these steps breed corruption. I will remove these and other bureaucracies which are bribe collecting stations.’’

But why does Mutua think he’s the man for the job?

‘‘I went to see President Moi once and he told me why he chose Uhuru Kenyatta for a successor,’’ Mutua says. ‘‘Moi told me he chose Uhuru because of African anthropology, and might have said very tribal things about what he thought of certain people and their inability to lead, but I listened to his reasoning. He told me his choice for successor was Mwai Kibaki, but Kibaki refused to join KANU and that was the dealbreaker. Uhuru came in as Moi’s second choice, much as he too has it in him. One time I was watching Uhuru give a speech and Amb. Muthaura told me, ‘‘One day this guy will be president.’’

Mutua too believes he has the thing, that thing that makes people presidents.

…

This project is a collaboration between

Debunk Media and the Star Newspaper.