You know that game where you’re asked if you were to have dinner with one person, dead or alive, who would you pick? I know you may already have your favorites, but the next time you’re asked that question, say Reuben Kigame, whether it’s a game you’re playing or you mean it. You’ll thank me later. That’s all I feel like saying and leaving it at that, but then I’ll be doing Reuben Kigame the sort of injustice he’s so accustomed to, that of always being reduced to nothing more than some blind mystical singing figure – and the ground around him shakes when he sings – and ignoring his entire range, be it his place in the intelligentsia – he’s at home discussing Negritude, Ngugi, Shakespeare, Plato or Okot p’Bitek, or his depth as a cultural connoisseur swinging from being rooted in reggae to jazz to blues to rhumba to calypso to Fela’s Afrobeat, or his patriotic varlour starting with street protests during the clamor for multipartism, or his unpopular crusade against the get-rich-quick abracadabra gospel. In a word, you need to know Reuben Kigame, whether he becomes Kenya’s next President (which he hopes he does) or not.

Part 1: The World Is Your Oyster

If Reuben Kigame had a dog, he’d name it Gorbachev, as an ode to Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union. When Kigame was a first year student at Kenyatta University in 1988, the 22 year old travelled to West Germany, but due to the dynamics of the then Cold War percolating into East and West Germany, Kigame couldn’t travel to East Germany. And so when he went to a cathedral and wrote a prayer request on a piece of paper which he then pinned to the wall, Kigame’s intercession was that the Berlin Wall should fall, so that the people of Germany could move freely. A year later, partly courtesy of Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost programs, the Cold War as we knew it lost steam and the Berlin Wall fell. For this and other sentimental reasons, Kigame held Gorbachev as one of his heroes. And yet Kigame’s fascination with either Gorbachev or the world of geopolitics hadn’t started with Kigame’s visit to Germany.

‘‘By the time I was ten I already had such an affinity for current affairs which I consumed from a shortwave radio through which I’d listen to the the likes of the BBC, Radio Moscow, Radio South Africa, Radio France International and Voice of America,’’ Kigame says exuberantly, ‘‘such that I am sitting in Vihiga but I’m listening to and learning guten morgen from Deutsche Welle, or I’m listening to Radio France and I’m learning bonjour, or I’m learning about the kwela flute from listening to Radio South Africa.’’

When Reuben Kigame was born on 13 March 1966 in Vihiga, the fifth born of seven came into a peasantry setup where his parents Richard and Susan were hardly making enough to keep the family afloat. And so Kigame’s father embarked on an economic exploration mission – which resulted in him becoming a long distance bus driver – which in turn made him an absentee. It is during one of his once-in-a-blue-moon appearances that Kigame’s father brought home the transistor radio, which Kigame wouldn’t let go of.

The radio became Kigame’s favorite toy not only on account that he liked listening to music and following world affairs, but also because he’d lost his sight, meaning he had to capitalize on his other senses – hearing, smelling, touching and tasting – to get a feel of things. One evening at the dinner table, a 3 year old Kigame had shot for the plate of ugali and missed it. His mother had wondered out aloud whether Kigame was going blind, because how could he miss the plate? Kigame had finally lost sight, having had cataracts in both his eyes, which had gone untreated and damaged his cornea. And so for the next four years, until he had to leave home, Kigame was showered with so much love and acceptance, so much so that his visual impairment didn’t turn into a pity party.

‘‘I am one of the most blessed people because I enjoyed a lot of family support since my parents and siblings never quite saw me as a blind person, and so I was very much integrated,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘We went out to the shamba together. I was shown my line to dig, my siblings were digging along, and the most interesting time was harvest time when I discovered what millet, maize and cassava looked like. I still get excited going back home. I guess that’s why leaving home for boarding school was difficult for me.’’

Kigame ended up at the Kibos School for the Blind in Kisumu, which in and of itself was a huge achievement on his mother’s part considering she wasn’t a woman of means.

‘‘I was in boarding school right from nursery school, but it wasn’t easy because as a child I was being plucked from a life and culture I liked, to go and be incarcerated for three months at a time,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘But either way I look back to that childhood with a lot of fondness because it is that ambiance of the ‘70s that really shaped me. Kibos School for the Blind was located right next to the Kibos Maximum Security Prison, and about a kilometer away was the Railway Station in the midst of the Nubian settlement.’’

Kigame says these details – the prison and the railway station – are significant for him.

‘‘Let’s begin with the prison next door, with the sirens going off whenever an inmate escaped and a police chase ensued,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘Then there was the railway station which for me – and Roger Whitaker sings about The Good Old E A R and H – wasn’t just about the whistle and the rumbling of the wheels but an exposure to long distance travel, because I knew if you went to the railway station you could get to Nairobi, which I had never been to before. And so for me when we discuss railway transport it is not something distant, something that I approach intellectually, but it is an emotive issue.’’

Kigame recalls his first trip on the Lunatic Express to Nairobi for the music festival, an experience he wishes every child could be accorded, but regrets seeing that rail hasn’t been made to work as a major component of public transport as is the case elsewhere.

But beside the prison and the railway station, Kibos School for the Blind was flanked by huge sugarcane plantations, which were sometimes tended to by prisoners. And so other than allowing Kigame and his schoolmates proximity to prisoners and prison culture, Kigame says pupils developed an appetite for sugarcane, such that it became one of the causes for delinquency. Occasionally, Kigame and others would attempt to go over the fence to grab some cane, only for them to endure strokes of the cane once busted. But aside from what Kigame terms peer-influenced misbehavior – he mentions puffing at something in the toilet since pupils would sneak in a cigarette – Kigame largely stuck to the straight and narrow. Then there was Kajulu Village nearby, which Kigame remembers for its ceremonies, the singing and dancing streaming into the school air.

‘‘I was plugged in with students from all over Kenya, some from Uganda and Tanzania, and I still think one of the best things that happened to me was being introduced very early to diversity in society,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘I learnt to pick up Luo, Kalenjin, Mijikenda and words from many other languages and got inculturated into some kind of national ethos. That’s why I get very depressed seeing people divided on the basis of ethnicity. It kills me. The cultures of this country intersected in my life since I was seven years old.’’

And yet if Kigame thought he’d seen the best of cultural-Kenya at Kibos, then a culture shock awaited him at the Thika School for the Blind where he reported to in 1981. After excelling in his Certificate of Primary Education by scoring an impressive 33 out of 36 points, Kigame had little in terms of O Level options other than the Thika School for the Blind, run by the Salvation Army just like Kibos. The education system as it was couldn’t accommodate visually impaired students in the average non-specialized schools.

‘‘The first thing I encountered was monolisation, touted as some kind of initiation into teenagehood where the big boys came and the first thing they did was to tell you they wanted to show you the school compound,’’ Kigame says with a laugh. ‘‘They then took you to places you didn’t want to go, the thorn bushes, where I got pricked a few times. Or they’d take away your shopping – the juice, biscuits and bread. The fact that it was an institution for the blind didn’t mean we didn’t suffer the fate of every other form one.’’

But on the more serious side of things, Kigame says Thika was worlds apart from Kibos. The education was more intense, and the student population comprised fellows from as far as Ethiopia, Sudan and Mozambique. Kigame’s own mentor, Chris Kakoma, the senior student whose piano-playing prowess Kigame looked up to, was Ugandan.

‘‘I emphasize this integration because seeing people by their last names isn’t how to do life,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘That integration rubbed into me so much so that when I met the love of my life, I was to discover she was Kikuyu only after the love had happened.’’

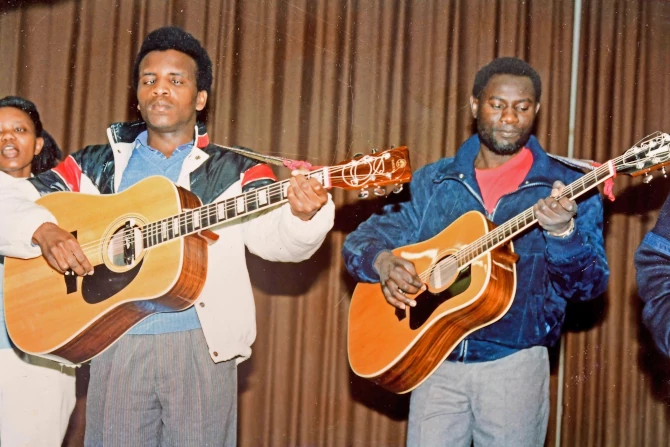

At Kibos, the furthest Kigame had gone in terms of playing an instrument was playing the percussion, but while at Thika, Kigame not only played the piano, the guitar and drums, but joined two different bands. With the Super Igniters, which did a lot more popstuff, Kigame played the drums, while with the Starlites, which focused more on the religious, Kigame did a lot more singing. And yet music wasn’t the center of Kigame’s life, much as it was integral. For instance, when Kigame got to form three, he dropped music in favour of literature, since to him music was but a hobby. Literature took over.

Fortunately for Kigame, once he was done with his O Levels, there were a few more A Level options for the blind, and so he opted for Thika High School next door since he yearned for learning in an integrated setup. Unfortunately, Kigame says the academic atmosphere was very unsupportive considering it lacked the requisite equipment – it didn’t have a brailer, which Kagame used to write in braille, and neither did it have a typewriter (Kigame had learnt to type at Kibos) – which he used for communication with sighted teachers and for assignments. After a term at the new school, Kigame retreated back to his alma mater, the Thika School for the Blind. This back and forth affected Kigame’s grades, seeing him miss studying Law by two points. Kigame was devastated.

‘‘I considered repeating,’’ Kigame says, ‘‘but then I decided not to cry over spilt milk.’’

In 1987, Kigame reported to Kenyatta University – kicking and screaming, where he took up his slot to study for a B. Ed degree majoring in History, Philosophy and Religious Studies. It is here that Kigame met Mercy Wanderwa, one of the student volunteers who had been seconded to read for Kigame. As the reading happened, a love grew, and soon the two were inseparable. As if fueling Kigame’s pursuit for a new Kenya, Mercy raided her father’s home library and brought with her copies of the Weekly Review and Beyond Magazine, which Kigame says he hid in between his clothes in the closet, lest he was profiled as a subversive. But even if Kigame hid the magazines, he couldn’t hide his thoughts on paper. And so whenever responding to his course work, Kigame wrote critically about the state of the nation, term papers which were graded but never returned. At one point after Kigame’s European trip, he wrote a booklet on communism. It vanished from his room. When Minister for Foreign Affairs Robert Ouko was assassinated in February 1990, Kigame joined the protests. And when Bishop Alexander Muge was killed in August 1990, Kigame joined the riots; he doesn’t call them protests any more.

‘‘Reuben wants to be MP for Mathare, so that he can rescue the people.’’

Kigame’s then girlfriend wrote in her diary.

Part 2: The Unapologetic Philosopher King

Beyond just bringing back memories of when he’d listen to the radio and learn Deutsch, Reuben Kigame’s 1988 trip to West Germany had one other significance. Much as it was his maiden out-of-the-country trip – he’s since been around the world, visited the United States at least 15 times – which first took him to Switzerland, where he underwent eye checkup to see if his eyesight was salvageable, Kigame recorded his second album in Berlin, having released an earlier one in 1987. But the biggest implication of the trip emanated from ‘‘Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career,’’ a book Kigame had picked up at the Thika School for the Blind and taken with him to Vihiga.

‘‘That book introduced me to the place of someone speaking up against what’s not right, in the way that Martin Luther stood up to the church, something that isn’t a common occurrence,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘And secondly, I saw a clergyman pursuing academics and that influenced me. Luther was very studious, and just like him I grew to love reading.’’

That book changed Kigame’s life forever – it radicalized him even – so that being in West Germany was a sort of pilgrimage to the land of Martin Luther, Kigame’s lifelong hero. Like Luther who stood against the sale of indulgences as he pinned his 95 theses on the door of the Wittenberg Cathedral, later on in life Kigame too embarked on the fight against the prosperity gospel and the concomitant sale of oil and soil. Combining this spiritual uprising and Kigame’s love for Gorbachev made for an interesting evangelist.

‘‘I learnt from Luther that if you’re a christian you don’t shy away from politics or from engaging society. The mistake the church is making today is dichotomizing faith and life, and that shouldn’t be the case,’’ Kigame posits. ‘‘Your faith informs how you live. It is that dichotomization that has brought us here, so that even when you announce you’re running for office the first reaction from the church is that politics is dirty. If you live as if faith is all about Sunday and a Friday kesha somewhere, then you miss the point.’’

Like Luther, Kigame loves the church enough to be its fiercest critic.

‘‘The contemporary Kenyan church is a letdown,’’ Kigame says when I ask him about the state of the church today. ‘‘It has gone further from Christ and become an empty shell of music and empty sermons, a faith based on greed and personality cults. It has refused to engage with politics, quite different from the likes of Henry Okullu, David Gitari, Ndingi Mwana a’Nzeki and Timothy Njoya. Those people spoke truth to power.’’

And what is Kigame’s view of the state of the nation?

‘‘I’d like to look at the state of the nation the way one looks at a patient in a hospital,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘Usually, you have the General Ward, the High Dependency Unit (HDU) and the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). I see Kenya in Jomo Kenyatta’s day as being in the General Ward. In Daniel arap Moi’s day we went to the HDU, then in Mwai Kibaki’s day we went back to the General Ward. But Uhuru and Ruto have taken Kenya right into the ICU. We are in collapse mode unless something drastic happens in the next election.’’

To Kigame, even if he’s the only one who will stand up to be counted – and he believes he isn’t the only one – he’s committed to go all the way to the ballot and vote out the current regime and all that it represents. It is here that Kigame opens up that for the longest time as people reduced him to just a singer, he’d been plotting an ideological revolution. I ask him what form the revolution will take. ‘‘You either have a bullet or ballot revolution,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘The bullet revolution never works. The best revolution is one in which you are a participant, not just giving instructions.’’ And what Utopia does he propose?

‘‘It’s not Utopia, it’s reality, it’s here, I feel it, you feel it, I touch it, everybody wants different,’’ Kigame says about his idea of a new Kenya. ‘‘It’s not a dream. We know things are bad. We know that we are cheated. We know that we are exploited. So we actually want something different. We will get different. We must get different and we will get different, and I am part of different. It is going to happen. And happening doesn’t mean that I become president, it just means that the discourse becomes different.’’

Kigame ropes in Esther from the Bible, and says he’ll face the king and tell him he’s naked.

‘‘Even if I perish,’’ Kigame says, ‘‘I perish.’’

When Malawian President Lazarus Chakwera visited Kenya in October 2021, one of the groups that went to meet him on the sidelines was a contingent of 12 representing the church. Among them was Reuben Kigame, who says he’s not necessarily a title-holder within the church since he hasn’t been ordained, but who was found worthy of an invite.

And when the group walked in to meet Chakwera, the Malawian’s first words were directed at Kigame. ‘‘Have you stopped singing those wonderful country songs?’’ Kigame was surprised that Chakwera knew he sang, and that the President also knew exactly one of the genres Kigame explores. ‘‘I still do,’’ Kigame replied. ‘‘Growing up I listened to your music and sang it with my family,’’ Chakwera said. ‘‘What you are aspiring to is correct. Go for it.’’ Kigame felt seen, something which isn’t common.

‘‘I was inculturated into the music,’’ Kigame says when I ask him what music means to him. ‘‘It has helped me express myself where words fail, where understanding fails, where limitation exists. But on the other hand, music helps me find my way away from the limitations of this world. Blaise Pascal says there is a God-shaped vacuum in the heart of every human. My music helps people fill that void in some form or shape.’’

29 albums later, Kigame still believes he hasn’t been heard. I ask him whether he is the lone voice in the wilderness. He says no, even the lone voice in the wilderness is heard. He isn’t the town crier, and pins it on the stereotypes that blind people should stick to singing by the roadside and receive alms. The other wrong assumption about him which doesn’t make people engage him and his work is that all he does is sing in church, and that he should stick there, when in fact he sees himself as one with the likes of Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Fela Kuti and Bob Marley, singers and citizens of the world who speak to the human condition more than just drop ballads.

‘‘It is beyond the music, it is beyond the sounds, it is beyond the idioms, it is what you believe because it comes through in the music,’’ Kigame says of his musical orientation. ‘‘If you believe in justice you’ll love Bob Marley. If you believe in diversity and culture you’ll like Fela Kuti. You’ll enjoy not just because of the aesthetic, but you’ll go beyond.’’

In Kigame’s first album, ‘What A Mighty God We Have’ released in 1987, there’s a song titled ‘Give Them Freedom’, which the singer wrote after watching the movie Sarafina. It was a response to apartheid. Then there were songs such as ‘Another Country’, ‘Why Kill Tonight’, ‘I have A Dream’, ‘Sweet Bunyore’ and ‘Africa Receive Your King’, all of which are social commentary but are rarely spoken about. Kigame’s latest, which is less than a month old, is ‘Tumechoka’, which he plays for my colleagues and I at his studio.

‘‘I sing about a lot of social stuff that people don’t listen to, and when they do,’’ Kigame says, ‘‘they don’t hear me.’’ To Kigame, people want him to go and bring the roof of the church building down with his powerful voice and instrumentals, and leave it at that. His going into society is frowned upon, and it’s not just in Christian circles. At the state level, Kigame has always been a frequent performer at functions, with President Mwai Kibaki going as far as awarding him the Order of the Golden Warrior for his service to music and media. However, Kigame says he won’t be invited to speak in places that matter.

‘‘Society is structured in such a way that persons with disability only make it to certain places – sing your song and go. If I spoke and if an able bodied person spoke, they’ll listen to the able bodied person. It’s like blind people aren’t supposed to be in politics.’’

Be that as it may, Kigame is still keen on engaging society’s entire breadth.

‘‘A lot of what people call secular isn’t secular,’‘ Kigame says. “Just because something isn’t sung in church doesn’t mean it’s secular. I use Bob Marley’s ‘Redemption Song’ to teach my students guitar. For me what is secular is what is destructive, derogatory. But anything that addresses itself to culture and life isn’t necessarily secular. Things that speak to lived reality are as godly as anything else.’’

This is how Kigame’s influences range from Bob Marley, UB40 and Alpha Blondy, to Kenny Rogers, Dolly Parton and Skeeter Davis, to Congolese bands of the 70s and 80s such as Mangelepa, Super Mazembe, Lipua Lipua, to East Africa Community acts like Jamhuri Jazz and DC Milimani, and the list goes on, to West, South and North Africa too. ‘‘I hear the world,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘I don’t know how else to consume the world.’’

I ask Kigame what keeps him going other than the music.

‘‘The first thing that drives me is my faith,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘I am a straight talker, my yes is a yes and my no is a no. Anyone can say bwana asifiwe or as-salamu alaykum, the issue is, is it just about rhetoric? I want to say like Paul said, ‘‘Follow me as I follow Christ.’’ I want people to look at me and not have to second guess what I stand for.’’

The second thing that drives Kigame is the Constitution, particularly Article 1, which rests sovereignty with the people. To Kigame, it’s God first, the people second, then his conviction as a disruptor third. Will Kigame be a theocrat considering the centrality of faith in his politics, or how does he plan to convince those who have question marks?

‘‘There are two kinds of theocracies – democratic and autocratic,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘God is a democrat. He says, ‘‘Come let us reason together.” Other theocracies are ‘‘I will kill you in the name of god.’’ Democratic theocracy never harmed anyone. It’s all about love, justice and equality. Those values will be true whether in a theocracy or not. If I became President everyone will be equal, even Christians won’t get any preferences.’’

And why should Kenyans vote for Reuben Kigame?

‘‘If Kenyans don’t vote for me, from 2023 onwards, Kenya will be exactly where it is if not worse because my competitors are coming in either opportunistically or to perpetuate the status quo,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘In me they will find someone who has eaten dirt with them, someone who feels them, someone who will guarantee Kenya’s posterity.’’

But here is Kigame’s biggest pitch.

‘‘Visual capability can be a problem,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘I think our leaders are seeing too much. There is a sense in which the ability to look with your eyes perpetuates greed because you admire too much of what you see, so that you look at a building, someone’s shamba, and develop covetousness. I believe one of our problems is that our leaders see too much. Maybe it’s time for Kenya to be led by someone who sees not with their eyes but with their hearts, someone who bypasses the visual and goes deep.’’

And here Kigame quotes King Lear in Shakepspeare’s ‘King Lear’, Act 4, Scene 6.

‘‘A man may see how this world goes with no eyes.’’

Part 3: Kigame’s Kalakuta Republic

It is a Thursday morning when my three colleagues and I – two cameramen and our executive producer – take a 6am Jambo Jet flight from Nairobi. We land in Eldoret just after 7am, take our ground transportation, make a pitstop and have breakfast, before getting to Reuben Kigame’s leafy home in the outskirts of the County of Champions, where Kigame’s wife Julie Alividza insists we must have breakfast, again. It seems we have little say in the matter. We oblige. Kigame joins us and skips small talk. We’re having tea and coffee talking about Kenya’s existential crisis, with Kigame’s sing-song yet powerful voice making the conversation less depressing. Things are bad. But do not despair. I shall fix them. We shall fix them. It is as if Kigame is speaking to his family.

In April 2006, Kenya’s and East Africa’s preeminent historian Prof. Bethwel Allan Ogot made one of the most profound yet damning statements about Kenya as we know it, or as we knew it. ‘‘Project Kenya is dead,’’ Ogot said. ‘‘The tribe has eaten the nation.’’ In December 2007, just over a year later, Ogot was vindicated in an I-told-you-so-much-as-I-wish-I-wasn’t-right way when the country went up in smoke following a disputed presidential election. Kenya as we knew it changed forever.

And so for Reuben Kigame whose entire life was spent mingling with people from all over Kenya from the time he was sent to boarding school aged seven – visually impaired students have limited choices when it comes to schooling, and almost always end up in the same institutions no matter which part of Kenya they come from – the answer was to create his own little republic, following in the footsteps of one his musical heroes, Fela Kuti, who named his home Kalakuta Republic and opened it up to anyone and everyone, except his country’s military dictators and their bloody thritsy agents who were personas non grata but who occasionally performed violent raids.

Kigame’s little republic is a not-so-old bungalow which gives you Colonial District Commissioner residence vibes courtesy of the extensive yet tasteful wood paneling, the aged but not out of place wall to wall carpets, the massive hallways, the red brick tile roof and the man-made forest engulfing the compound. Were it not for the need to catch some sunshine, Kigame says he would have covered the house in a canopy. And no, no one is allowed to cut down a single tree. There will be a problem if anyone attempts.

You walk into Kigame’s kei-apple secured compound – you can’t see anything from the outside, and spot on your right two shipping containers which have been turned into the reception area for his music school. On the left is a series of classrooms, each of them dedicated to the teaching of a musical instrument. In one classroom there is a set of guitars hung on the wall, in another there is a sparkling drum set. Then there’s a little performance room, where Kigame says students showcase their newly acquired skills to their parents once the learning is complete. Next to the classrooms is a sole shipping container which used to house Kigame’s radio station, located next to a Safaricom mast. Then there’s the tarmacked basketball court which leads you into the main house, where Kigame has turned the former garage into a fully fledged recording studio.

‘‘Life happens here,’’ Kigame says when he shows me around. ‘‘I operate from here to the world, and only the rules that I live by operate here. You can’t smoke. You can’t insult anyone. If you come here you feel the peace, and it can happen, just give me more room. I am no dictator. I listen to my children and my wife. If we can’t listen we can’t lead. If we all believed in something then lived it out, this society will change.’’

We see a lot of comings and goings around the compound, and even our interview gets interrupted a few times when a young lad or lady pops in wanting to see Kigame. At some point a young man opens the door, then he and Kigame start conversing in Lingala. ‘‘Ozana biloko,’’ Kigame goes. ‘‘Ozana yo… nakobetela yo,’’ I manage to pick from Kigame. Was that Lingala? Yes it was, Kigame confirms. The young man is one of his musical mentees. There are usually many around the compound, but a lot of them are now back in school. Later on another young man shows up and speaks to Kigame in Kinyore. They all call him Papa around the compound. Kigame is at ease throughout, and says, ‘‘This is how we live here.’’ There are no pretensions.

Kigame says he lives the way he does because of Kibos School for the Blind.

‘‘Most times musical instruments were under lock and key, so we tried our fingers on the piano only when the chapel prefect forgot to lock it up,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘Now I have a piano in my house and I don’t ever want to see my children or any other child restricted from accessing it because growing up, that exposure itself is what builds you. The child should be able to break a few things, to experiment, so that they can pick up skills. It informs my approach to mentorship because I let young people make mistakes around me, since that’s the only way you can correct them and show them the right way.’’

And indeed, Kigame’s piano is unrestricted. Before we settle for the interview, my executive producer pulls a quick one and plays a couple of tunes on the piano. They say they’re refreshing their skills which were last put to the test in primary school. Later on, Kigame himself does the onus and plays us a few of his favorite songs both on the piano and on one of his many guitars. And when Kigame shifts from presidential aspirant to musician, the mood in the room shifts, silence falls all round and his rattling voice pierces the air as if he were performing for a huge crowd in concert. What similarly stands out is that Kigame navigates his environment with little assistance, knowing where to turn and where to sit. It’s truly his sanctuary.

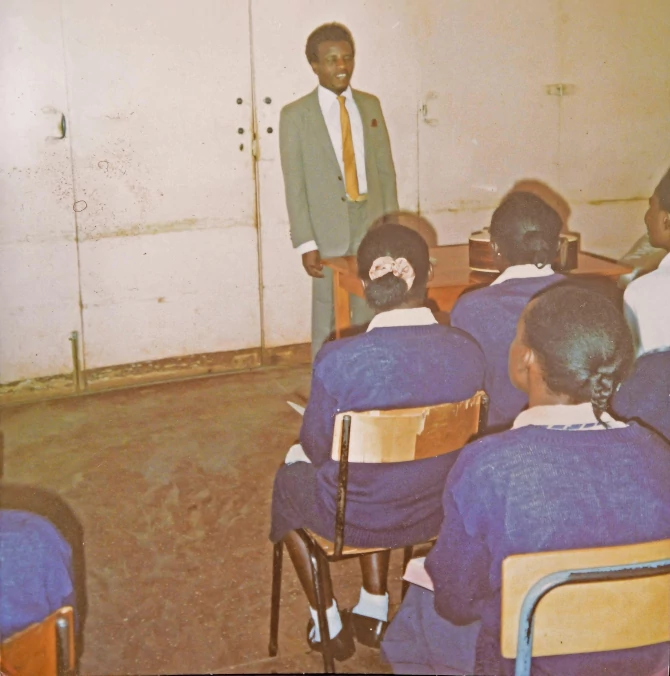

After leaving Kenyatta University in 1990, Kigame was posted as a teacher at Maryhill School, where he taught History, Christian Religious Education and Social Education and Ethics. Much as he was excelling as a teacher – he led the Christian Union, founded the Journalism Club, and was part of the Drama Club where he wrote political plays for the students, teaching seemed a little restricting for Kigame, and so he quit after four years. By this time, Kigame had married his college sweetheart Mercy Wanderwa, with whom they had three daughters, Shalom, Shekinah and Shema.

Kigame’s first stop was the Youth for Christ Ministries, where he worked for a year as Ministries Coordinator before deciding it wasn’t for him. He then set up Word of Truth Ministries, the platform which Kigame uses to date in his spiritual and political work. By this time, Kigame’s music and speaking engagements were in demand, and media houses starting with the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation, followed by the Royal Media, Family Media and Hope FM all came calling. As Kigame was working with these stations, he applied for his own radio licence in 2000, but then the only available frequencies were out of Nairobi, unless someone paid handsomely. And so after living in Nairobi’s Woodlands Road for 10 years with his kids attending St. Georges Primary School, Kigame decided to move to Eldoret in 2004. The radio frequency was granted in 2005. Unfortunately, Kigame’s wife Mercy was involved in a fatal road accident in 2006.

‘‘When my wife passed I dropped out of the long distance course I was studying for, and completely lost interest in certain things,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘Interestingly, my late wife Mercy was the daughter of an Angican priest, Canon Joseph Mwangi from Kirinyaga, and when I remarried later on, I learnt that my wife Julie is the granddaughter of yet another Anglican priest, Canon Esau Oywaya from Maseno.’’

Kigame has a son, Yeshua, whom he likes to call Yesh, with his wife Julie. Yesh comes back from school when my colleagues and I are about to leave, and looks shyly sad having missed the session. He’s the one who handles a lot of his father’s Zoom calls and the lot, call him the Kigame techie.

As I speak to Kigame, he leads me into his study, which is covered with books all around – encyclopedias, texts one music history, pop culture, religion, politics, you name it. Kigame tells me the collection contains his favorite books which no one takes away, but he has four times that number of books packed in boxes due to renovations. It is here that Kigame tells me that if elected, he will lead Kenya as a philosopher king, such that if there is debate between building an expressway and sparing people’s homes, human dignity will come first. Kigame hastens to add that he is not arrogant enough to believe that it is only philosopher kings who can lead. I take Kigame’s concession. Also in the study are four pairs of cowboy boots and a number of cowboy hats, for when Kigame’s country music bug bites.

In 2010, Kigame started an MA in Journalism and Media Studies, in which he analyzed the electronic pulpit and its impact, then embarked on his PhD on World Christianity in 2018, in which he’s writing about decolonizing African christianity, all these as part of his life project on Apologetics, on which he’s written the seminal ‘Christian Apologetics Through African Eyes’. I ask Kigame to expound on Apologetics, and he tells me it comes from the Greek word apologia, which means speaking away accusations or misunderstanding, meaning all he does is turn Christianity inside out as he engages interlocutors of all kinds, in his quest to make them appreciate its truest essence.

But what really are the things Kigame wants to deal with once he becomes president? He lists them. Striking against corruption – he’ll jail some people if they don’t atone and return what they’ve stolen. One has to put a bandaid on the patient before anything else. Kigame’s next priority will be to tackle hunger by disrupting the illegal import schemes, fixing storage and distribution. The third is fixing the national debt – live below our means and restructure existing debt. The fourth is regreening Kenya – if you violate the environment it will violate you. And the fifth is national cohesion – he was born in Vihiga, he schooled in Kisumu and Thika from age seven, he married a Kikuyu then a Luhya, and lives in Uasin Gishu.

‘‘I stand for a reboot of the nation, so that we have the cleanup of the soul, not just what’s visible and is external,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘We are in the hands of a few countrymen and women who are worse than the British colonial masters, because they are born here, they are Kenyans like us, but they oppress in a manner that even a foreigner does not oppress. A few families, a few individuals, have brought Kenya to a point where we have a few well endowed people and multitudes living below the poverty line. 58 years after independence, we’re still hungry. Those few families and a few of their friends are hoarding every possible resource because they are closer to the jar, they have acquired them, rightly or wrongly. They are stealing but we don’t like calling them thieves, we’re fighting for those who are pillaging our futures. We need to be angry enough.’’

On the realpolitik side of things, Kigame says he can’t yet put all his cards on the table, but volunteers that he is part of The Eagles National Alliance (TENA), a Christian alliance which brings together between 5 and 9 political parties. Then there is Kongamano La Mageuzi, in which a number of progressive political parties and civil society groups coalesce. Kigame’s other centers of organizing are artists and creators, people with disability, teachers – he was one before, christian media – he trained a good number of them. Kigame believes with these networks he’s already set off at dawn.

Will Kigame go into alliances with other politicians?

‘‘There’s no room for compromise for me, especially with anyone who has been in government before who is running,’’ Kigame says. ‘‘I will not sit with them to negotiate anything because they are the reason why we are where we are. I am not running because I want a position or I am hungry. I am in this because I want to see Kenyan citizens be able to smile again and for Kenya to finally breathe a sigh of relief.’’

By the time my colleagues and I are landing in Nairobi at 7pm, we feel like we are back from a different country, call it Kigame Land, where we were fed – lunch too was served just as we were planning to leave and eat on our way to the airport – and got to experience the musical, intellectual and spiritual firepower – Kigame fashions himself after the likes of Léopold Sédar Senghor – of someone who may have something to offer Kenya, but who may not be given the degree of due consideration as extended to his competitors. At least now you won’t say you don’t know Reuben Kigame.

…

This project is a collaboration between

Debunk Media and the Star Newspaper.