There is no better way to describe Prof. Kivutha Kibwana other than by looking at two men from India, Mohandas Gandhi and Bhimrao Ramji Ambedka. Gandhi, a man from an upper caste, became world renowned for his meekness, activism and controversies, while Ambedka, a man from the lowest caste, wasn’t necessarily a global celebrity but rose to become an Ivy League trained lawyer and father of the Indian constitution who changed the lives of India’s lower caste immeasurably. And so to date, as debate rages on as to who is the greatest between Gandhi and Ambedka, Kivutha Kibwana offers a solution to the puzzle. Kibwana brings Gandhi’s meekness and Ambedka’s intellect and commitment to changing the lives of the common man and woman, in his people-centered approach to governance.

Part 1: Finding a Way or Making One

There is a story that Makueni Governor Prof. Kivutha Kibwana’s wife Nazi Kivutha doesn’t like him repeating because she says it is deeply embarrassing. And yet when I meet Kibwana at his hideaway of a private office tucked away in Nairobi’s Kileleshwa neighbourhood, the Governor laughs and shares the tale without any qualms. In true Kibwana style, the office is furnished in the most austere way possible, giving one a sense that if Kibwana could have the option of not having an office at all, he would go for it. The building, a refurbished old bungalow, is set in an expansive compound whose signage doesn’t reveal it could be a governor’s office, nondescript without being so. Kibwana doesn’t like glitter.

By the time Kibwana was enrolling at Machakos School for his O Levels, the only thing the 13 year old aspired for in life was to get a job so he could afford food. It was that simple. Born to a family of 29 children – Kibwana’s mother had 13 while his step mother had 16 offsprings – Kibwana spent his early years first at his grandfather’s home then later at his aunt’s, the two places where he was introduced to school, but where food was hard to come by. It was while at his grandfather’s that Kibwana accidentally enrolled for school, out of boredom and curiosity.

‘‘My grandfather’s baby brother and my aunt were attending a nearby school,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘and so I started following them. No one imagined I was learning anything, but in reality I was enjoying the classes and learning a lot of things. Unfortunately, the school had only class one and two, meaning when one rose to class two and completed the syllabus, they circled back to class one to start all over again. Luckily, this was around the time I moved to my aunt’s place and enrolled in a better school with more classes.’’

Kibwana’s aunt was a widow and had no means to support herself. And so the six year old used to carry boiled maize and wild vegetables to school for his lunch. But once in school, Kibwana would sit with children from well off families, who carried better varieties of dishes which they shared with him, until such a time when they decided he wasn’t worthy of their generosity on account that Kibwana brought terrible dishes. Kibwana got banished and cried a lot.

‘‘That day,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘I vowed to study hard so I could afford food.’’

Kibwana never told his parents he was suffering lest they withdrew him from school. And much as he missed his parents and the rest of his siblings, Kibwana made up for this by attending Friday and Saturday night folklore sessions in the village, where he developed his love for poetry and theatre. These sessions proved useful later on when Kibwana started writing in Kikamba.

And so for all intents and purposes, Machakos School was a form of Utopia for Kibwana. There was plenty of food, and all he needed to do was show up at the dining hall. It is also here that Kibwana had worn his first pair of shoes, and met people from all over Kenya for the first time. This is the point where that story which Nazi Kivutha detests comes in.

‘‘In my early days at Machakos School,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘I went to the toilet for the big job, and as I got busy, I kept looking over my shoulder and seeing some chain hanging. And so in the curiosity of a young man, I pulled the chain to see what would happen, only for a loud noise to descend on the room. I dashed out even before I had buttoned up properly, afraid that I had broken something and was about to get into serious trouble with the school administration.’’

Kibwana waited for his crime to be discovered but nothing was forthcoming. It was at this point that he got the courage to inquire from a form four what the pulling of the chain in the toilet meant, only to be reprimanded, ‘‘Don’t be a fool. You simply flushed the toilet.’’ This toilet incident, Kibwana says, was closely related to another misdemeanor where during a session at the Physics laboratory, an adventurous Kibwana was messing around with a socket, only for his British teacher to rush to him and shout, ‘‘You stupid boy, do you want to kill yourself?’’ From that point on, Physics and Kibwana became like water and electricity.

But aside from these early day mishaps, Kibwana generally enjoyed his time at Machakos School. During his A Levels, Kibwana opted to study the Arts, keen on studying Literature at the university. He had written plays and acted at the National Drama Festivals, and much as he didn’t play any sports actively, Kibwana remembers participating in a 60 kilometer walk as a form one, walking from Machakos School to City Hall in Nairobi to raise funds for the school swimming pool. Kibwana was the last one to arrive at City Hall, and was gifted 10 shillings.

When Kivutha Kibwana arrived at the University of Nairobi in 1973 aged 19, 26 year old Chief Justice emeritus Dr. Willy Mutunga was just about to be hired to teach Commercial Law at the institution. By the time Mutunga embarked on his lectures, Kibwana was in his second year.

‘‘Back then he was simply known as John Mike, John being his baptismal and Michael his confirmation name in the Roman Catholic denomination,’’ Mutunga says when I reach out to him and ask about his earliest memories of Kibwana, whom he taught and mentored. ‘‘He was one of the brilliant students in class, and I also knew he spent a lot of time with the radicals in the Literature Department, joining their Free Traveling Theater project that took students all over the country performing plays. All plays, without exception, had radical messages.’’ At the Literature Department were the likes of Okot p’Bitek and Ngugi wa Thiongo.

‘‘Those days, much as I was a student of law,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘I could pick whichever other lectures I wanted to attend just for my own general knowledge, since the practice wasn’t prohibited and classes were small in size. I would attend Okot p’Bitek’s literature classes, and those of many others.’’ For Kibwana, it was all a thirst for inner knowledge more than anything else.

On his part, Mutunga doesn’t shy away from the fact that he was deliberate in how he taught his students, saying that as a graduate of the University of Dar es Salaam – which Mutunga calls the Mecca of revolutionary university education – he had mastered teaching methods that valued the intellect of the student, embracing history, socio-economics, culture and politics.

‘‘Kibwana was one of the key adherents of this approach given his practical multidisciplinary pursuits at the university,’’ Mutunga says, ‘‘and if I played any role in his academic and other progression, then it is that he and others became brilliant disciples of the radical teaching method of the law.’’ Kibwana corroborates this.

‘‘There had been conservative professors who taught you law so that you could became a big time lawyer, make a lot of money and have a big name,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘but then came a new breed of professors, people like Mutunga, who taught us that education can be used to serve the people, and in me they found fertile soil to receive knowledge that would help me actualize some of the things that I thought were right as a young person. So yes, whether it is Willy Mutunga or Ngugi wa Thiongo, those of a reformist and progressive bent – they were of course called radicals, socialists and even communists – they influenced my generation in a major way.’’

And yet, for Kibwana, these ideals went deeper than what his professors taught him. ‘‘For me, it wasn’t theoretical radicalism at all,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘It was something borne from my lived experiences, and maybe that is why it is usually consistent, because it is something from childhood, something from boyhood, and it is something present even now in my maturity.’’

Kibwana tells me of how while in primary school, whenever his aunt went to the shopping center in Emali, all she brought back in the name of meat were bones. Unfortunately, Kibwana says, she passed away before he got to ask her whether she used to be given the bones for free or whether she used to buy them. This is why whenever a goat died in the village, Kibwana and others got excited since that was their opportunity to eat real meat, a rare commodity.

‘‘Tied to this was my religious beliefs, where we are taught to love our neighbours as we love ourselves, and lessons from Akamba folklore where the bad guys always ended up in some misfortune or other,’’ Kibwana says. Western religion, African folklore and radical intellectualism had intersected in Kibwana.

But beyond listening to his professors, Kibwana was also a frontline student activist. ‘‘I was the minister for information and propaganda in Oluoch Obura’s government,’’ Kibwana says with a chuckle. ‘‘I know we had unusual names for our roles, but those days students were really unhappy with the Kenyatta government, and our heroes were people like J.M. Kariuki and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, who remains my hero to date. It was a difficult terrain to navigate.’’

Upon completion of his undergraduate degree in law, Kibwana earned two scholarships to study for a postgraduate degree, one from the University of Nairobi and another from the University of London. Kibwana opted for the University of London. ‘‘The thing about these universities is that you got a first class education,’’ Kibwana says of his time abroad. ‘‘Teachers were sent on annual sabbaticals in industry and government to learn what was really happening. We also had 24 hour libraries, mingling with students from all over the world.’’

To Kibwana, it was all about books.

After a year in London, Kibwana returned to Kenya and took up a teaching role at the University of Nairobi. He was only 23 years old, and hadn’t had occasion to attend the Kenya School of Law (KSL) since its then principal, the British barrister Tudor Jackson, wasn’t too eager to have Kibwana at the institution following Kibwana’s history of student activism. But Kibwana was unbothered, much as he attended the KSL later. His entire academic life was ahead of him, and he would finally get to work alongside his mentors.

‘‘Kibwana and I built a comradeship when he came back from the University of London and joined the Faculty of Law as a colleague and comrade,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘Having him in the radical and progressive wing of the Faculty and the University generally was important. Our numbers (initially there were four of us who I could count as radical teachers and thinkers—the late Dr. Oki Ooko Ombaka, Professor SBO Gutto, and Professor Robert Martin, a Canadian scholar) increased. The issue of teaching approach came up and we had a retreat to discuss it. This was a serious battle/struggle of ideas in the teaching of law which our group won courtesy of the moderates in the Faculty teaming up with the radicals and the radical student representatives in the Faculty Board.’’

I ask Mutunga what one memory of his comradeship with Kibwana sticks out the most.

‘‘One memory that stands out is the visit by Kibwana and his wife Nazi to Industrial Area Remand Prison where I was held in custody for two months facing sedition charges,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘These charges were later dropped and I was detained without trial for 14 months. Kibwana was the only colleague from the Faculty to visit me although the other progressive colleagues did come to see me during court sessions. Nazi was pregnant with Ngumbau. The stench in the prison was too much for her and she fainted. I have never forgotten that act of courage and humanity by the two of them.’’

It wasn’t long before Kibwana was off to Harvard University for his second masters degree.

Part 2: A Man and His Constitution

For Kivutha Kibwana, leaving Kenya and going to study at Harvard in 1983 was an act of God. Around that time, going all the way to 1988 when Kibwana returned after earning his doctorate in Constitutional Law from George Washington University, a number of Kibwana’s comrades had either fled the country, been detained or died from state-inflicted complications.

By the time Kibwana was leaving Kenya, his teacher and mentor Willy Mutunga was already a guest of the state, an indication that were Kibwana to hang around Nairobi longer, then he too would have found himself cooling his heels in one of the state’s detention dungeons. And it wasn’t that Kibwana and others were looking for trouble. The state, too, was provoking them.

‘‘Before I left for the University of London,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘the management at the University of Nairobi had asked us to become members of KANU, and I remember saying an emphatic no! We were even enticed that we didn’t have to pay cash for the party membership, that it would be deducted from our salaries. I said I’d rather get kicked out of the university than join KANU.’’

These were the sorts of circumstances Kibwana left behind when he took off to Harvard, where Mutunga tells me initially, Kibwana had one too many drinks before he totally abandoned the bottle as he set off for his PhD. ‘‘The road from Harvard to George Washington compares very well with Paul’s road to Damascus,’’ Mutunga says. It is possibly during this Harvard-George Washington Damascene moment that Kibwana had an epiphany of just what a hard task lay ahead of him in the liberation of Kenya, because Kibwana’s PhD in Constitutional Law became one of the cornerstones in the clamor for and eventual realization of Kenya’s second republic.

‘‘I came back to Kenya in 1988, at a time when Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika was in top gear, a year before the fall of the Berlin Wall,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘The Cold War was quickly dying down, with countries such as the UK, the US and others which had previously supported certain African despots changing tact and abandoning most of them. Time was ripe to push for change.’’

Kibwana re-took his teaching job at the University of Nairobi, by which time Willy Mutunga had been sacked post-detention, alongside other enemies of the state such as Ngugi wa Thiong’o. As the country’s political opposition was coalescing around what would eventually become FORD and was hurtling towards the repeal of Section 2(a) and consequently the 1992 multiparty elections, Kibwana moved quietly to establish a base, networks and structures upon which the change movement would find its footing and anchor itself in playing the looming long game.

‘‘President Moi and his men thought we were busy bodies wasting time holding symposia and conferences in hotels,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘but the strategy was that first we had to understand the issues, then prepare material, then used that material to spark conversation, before attacking.’’

There was a formula to the madness.

‘‘After Kibwana’s return, we joined forces in the embryonic human rights movement,’’ Mutunga says, ‘‘with him and others setting up the Center for Law and Research International (CLARION) and I and others setting up the Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC).’’ Among those who worked with Kibwana at CLARION were Supreme Court Justice Dr. Smokin Wanjala, former Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR) Commissioner Lawrence Mute, former Director of the University of Nairobi’s Institute for Development Studies (IDS) Prof. Winnie Mitullah, the late Prof. Symonds Kichamu Akivaga and Prof. Karuti Kanyinga.

‘‘We had a lot of conferences discussing what a new Kenya could look like, what the constitution of such a country would be,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘and here my PhD in Constitutional Law came in handy because a lot of the things we wrote with the likes of Smokin, Akivaga, Kimondo, Mute, Karuti, Mitula and many others fed into what eventually became the 2010 Constitution.’’

Kibwana says he progressively linked up with various courageous clergymen – Rev. Timothy Njoya, Bishop Henry Okullu, Archbishop Manases Kuria, Archbishop David Gitari, Archbishop Ndingi Mwan a’Nzeki, among others, in seeking to use churches as one of the frontlines for expanding political consciousness. But beyond the church,Kibwana had an Africa-wide network of scholars and thinkers; Adama Dieng from Senegal, Joe Oloka Onyango from Uganda, Issa Shivji from Tanzania, among others whom he met as an external examiner in a number of African universities. Through this group, Kibwana sharpened his ideas of what a new Kenya would look like in the course of their reimagining Africa’s future in the world.

It is this civic, political, intellectual and spiritual momentum that culminated in the National Constituent Assembly (NCA) and the National Convention Executive Council (NCEC), of which Kibwana became spokesman. The NCA and the NCEC became convenors of the civil society, the religious sector, the political opposition in parliament, and citizens – Wanjiku in Moi’s lexicon.

‘‘From 1996 to 1998, through the NCA-NCEC, Kibwana and I, and many others, got involved in various social movements that demanded the writing of a new Constitution,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘We teamed up with opposition political parties and achieved a lot in the project, first the piecemeal constitutional and legal reforms followed by agitations that gave birth to two parallel parliamentary (precursor to the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission – CKRC) and civil society (Ufungamano Initiative) constitution-making processes. Prof. Yash Pal Ghai succeeded in unifying both initiatives into the CKRC, and the rest is history.’’

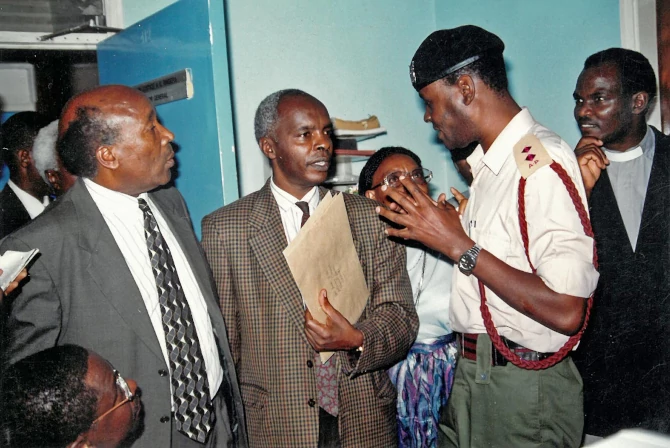

Throughout this period, Kibwana had become more visible and outspoken.

‘‘During those NCEC days,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘we were under serious state surveillance, including being approached by emissaries sent by President Moi. One time Mzee Mulu Mutisya was asked to look for me and take me to State House – I respected him as an elder because that’s what you are taught in those folklore sessions – and so I listened to him as he told me, ‘‘Why don’t you go and see the President and tell him what you guys want?’’ I told him that I can’t go on my own because there was nothing I could discuss with the President on my own, but that if the President wanted to hear us out then we had to meet him as the whole NCEC.’’

Mulu Mutisya couldn’t believe what a tough nut to crack Kibwana was.

‘‘After he failed to convince me to go and meet Moi,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘Mulu Mutisya told me my mother must have taken the Mau Mau oath – some of the people from Ukambani were in Mau Mau – and that I must have suckled milk which had the oath in it, because I was stubborn.’’ And when Mulu Mutisya offered to give Kibwana money for transport after their meeting, Kibwana asked him to instead give the money to the friend who had given Kibwana a lift to the meeting, someone Mulu Mutisya respected. Mulu Mutisya was dumbfounded. ‘‘As much as people say he was uneducated and so on,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘Mulu Mutisya was a leader worth his salt unlike a lot of leaders today. He did not bulldoze his way even when you didn’t agree with him or fancy himself as being better than others. I respected that about him.’’

After Mulu Mutisya failed, a senior Kamba intelligence officer was sent to Kibwana.

‘‘The spy came to persuade me to go and meet President Moi,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘telling me they had looked at my bank accounts – they weren’t many – and seen there wasn’t any money there. The offer was that if I agreed to go and meet the President, I would be given money, which could be sent overseas from where I could go and pick it. I told the man yes, I will take the money but only on condition that every Kenyan was going to be given money.’’ Kibwana chuckles.

Then there were the physical attacks, economic sabotage, and so on, but Kibwana soldiered on.

‘‘During the mass action in 1997 (May, June, July, August, September and October) Kibwana organically became the Spokesperson of the NCA-NCEC. The politicians in the movement did not trust each other for any one of them to undertake that role,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘Kibwana had emerged as our overall leader in the same manner James Orengo had emerged as our leader in press conferences and on the streets. Kibwana’s leadership grew in stature and his name featured prominently alongside that of Moi.’’

As the 1997 general election approached, some members of the broad coalition encompassing the civil society, the religious groups and the political opposition started getting jittery. The parliamentary opposition parties were divided as ever, meaning President Moi would easily win re-election unless a unity pact was crafted. There were also fears that unless some form of reforms were done, the elections wouldn’t be free and fair due to state interference at all stages and levels. It is with this backdrop that the Inter Parties Parliamentary Group (IPPG) was born, to try and enact a set of minimum electoral and other reforms before the 1997 general election.

Around that time, Kibwana, Mutunga and other vanguards of the NCA-NCEC used to meet every week with leaders of parliamentary opposition parties including Raila Odinga and Mwai Kibaki, alongside progressives such as Martha Karua, James Orengo and Anyang’ Nyong’o. The idea had always been that the group would either stick together or split up and get hanged separately, and the IPPG process became a mini-point of departure. By this time, in the public eye, it was the likes of Kibwana who were leading the movement, while politicians played second fiddle.

‘‘There was a huge debate as to whether we should support piecemeal reforms or push for comprehensive reforms as originally intended,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘and I totally understood where proponents of comprehensive reforms were coming from. A lot of lives had been lost, a lot of comrades had been maimed and imprisoned, and so on, and so there was a sense that the price paid that far was so high for us to settle for less. We had to finish the job, not do half a job.’’

But then elements within the Moi state saw an opportunity.

‘‘Nicholas Biwott played a key role in urging our political friends to abandon us,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘telling them how could they be subservient to us, unelected individuals. But Mutunga would say, if you have a good idea then that’s enough. You don’t have to be elected. All you need to do is to sell the idea to the masses.’’

A divide emerged. The politicians went for IPPG, with the promise that they could appoint a few commissioners of their choice to sit in the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK), among other goodies. The civil society group felt betrayed, and expressed as much to their political friends. However, looking back, Kibwana thinks they should have supported the IPPG. In later years, Kibwana found it difficult convincing Zimbabwe’s Morgan Tsvangirai to accept piecemeal reforms as a tactic, because like him in 1997, Tsvangirai wanted everything or nothing. That is how Zimbabwe missed a window for minimum reforms. Luckily for Kibwana, Kenya’s constitution making story had what they imagined was a happy ending. But beyond their pursuit for reforms, the opposition needed to unite or perish.

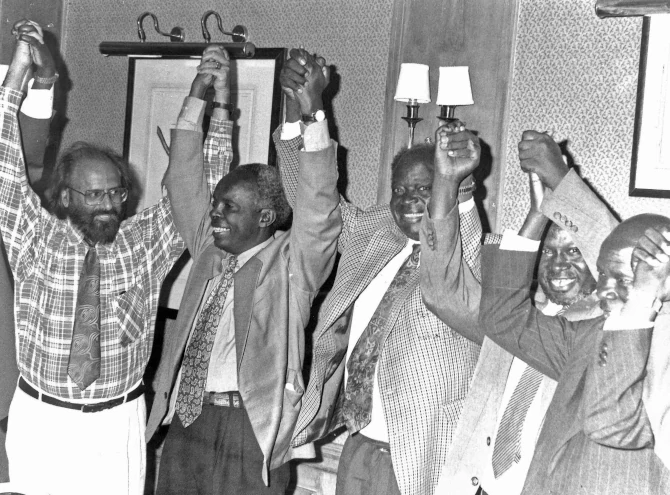

‘‘There was always the issue of the leaders of the opposition never agreeing on one presidential flag bearer, and that is how Kibwana’s name came up as an obvious alternative,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘I do not recall this issue being discussed formally in the NCA-NCEC. Indeed, it is my belief that the opposition political parties feared this people-driven demand for one presidential candidate from the opposition. This may explain why they trooped out of NCA-NCEC to join in the IPPG initiative, which Moi brilliantly managed resulting in his victory in 1997.’’

Kibwana confirms that indeed all the opposition leaders were in on his candidature.

‘‘I had played a leading role in the conversations on what a new Kenya would look like, and also worked closely with donors who trusted me in terms of identifying credible groups which could be funded in order to assist the democratization process,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘These, and other factors must have contributed to the opposition approaching me to be their compromise candidate. But we were committed to having a new constitution, and so the solution wasn’t just getting a new leadership. Because fundamentally, if you don’t change the rules even new players will find it hard to play. It is for this reason that I declined the offer.’’ Kibwana was 43.

On his part, Mutunga thinks Kibwana should have taken the offer and run.

‘‘After the IPPG was formed, some radical elements within the NCA-NCEC were of the view that it was a great opportunity for civil society to form a party and contest the 1997 presidential election seeing that the parliamentary opposition had bolted,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘There was no consensus and I do not recall us getting to implement the idea. If that had happened, we clearly had a candidate in Kibwana. Looking back, we missed a great opportunity to start a movement for alternative political leadership which is currently a burning political question in Kenya.’’

Does Kibwana have any regrets? None whatsoever.

It was under these circumstances that towards the 2002 general election, Mutunga played the leading role in uniting three opposition stalwarts, Charity Ngilu, Mwai Kibaki and Michael Kijana Wamalwa to form the nucleus of what became the united opposition behemoth which dislodged independence party KANU from power. At this point, Kibwana decided it was time he followed the constitution making process to parliament, since the promise of the united opposition was that once they took power, a new constitution was high up in their priority list. But as Kibwana and others rushed into government, they left behind a burning house.

‘‘We did not have a well thought out succession plan within the civil society,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘and so a lot of things went haywire, partly due to lack of funding. We had not thought of sustainability, and donors were saying because we had a democratic government in place, they now wanted to fund its programs. It was as if the revolution was over.’’

That wasn’t all.

‘‘A lot of the younger cadres within the civil society thought those of us who went into politics and government were betrayers,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘I remember Mutunga trying to talk about high politics, where even this group of reformers needed to find a foothold in the politics of the day so that they could influence the implementation of whatever change had occurred, but that idea was shot down and we were counted as betrayers. In 1997, we had called the political opposition betrayers for going back to parliament to join the IPPG. In 2002, myself and others were now the new betrayers. Unfortunately, there was no structured collaboration between those of us in government and those outside, and in the end, the civil society found itself isolated, in a Siberia of sorts.’’

But currently, Kibwana says, there is a renaissance.

‘‘We had imagined that passing a constitution was enough,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘but it wasn’t.’’

Part 3: Dictatorship of the Proletariat

When Kivutha Kibwana became an MP in 2002, the expectation was that he would become a cabinet minister due to his popularity within the pro-reform movement. But that didn’t happen.

‘‘For the first six months after his election, Mwai Kibaki kept asking those around him where Kibwana was, but he wasn’t getting any answers,’’ Kibwana says, aware that Kibaki had a soft spot for him. ‘‘After he suffered a stroke, Kibaki wasn’t very coherent, and those around him who didn’t like my ways seemed to have blocked certain communication channels. Eventually, Kibaki and I reconnected and he made me an assistant minister in the Office of the President.’’

Like a lot of his comrades who were rookies in government, Kibwana took a minute before making the shift from activist to political bureaucrat. Within months of his appointment, Kibwana got in trouble after he and Kibwezi MP Kalembe Ndile joined agitations for land by squatters in Ukambani. ‘‘I was told this is not how a minister behaves,’’ Kibwana says with a chuckle. As if that wasn’t enough, Kibwana joined Garsen MP Danson Mungatana in critiquing the government not too long after. He was quickly moved from the Office of the President to the Office of the Vice President. Maybe Kibaki had made a mistake appointing him, Kibwana’s detractors must’ve thought. But Kibaki still had bigger plans for Kibwana, because barely a year later Kibaki made Kibwana Minister for Environment and Natural Resources, with extra duties.

‘‘Just as I was appointed in the Ministry of Environment, a vacancy arose in the Ministry of Lands, and Kibaki asked me to act as minister, a role I doubled in for 17 months straight.’’

To juggle between the two ministries, Kibwana crafted a plan where he worked in one ministry during the day and moved to the other in the evening, leaving the office at midnight on most days. ‘‘Those especially at the Ministry of Lands were lamenting,’’ Kibwana says with a laugh. ‘‘They told me, ‘‘This is not how we are used to doing things here.’’’’ Kibwana was undeterred.

On the environment front, Kibwana became president of the Climate Change Convention, and using his extensive knowledge of Land Law, Kibwana took advantage of his stint in the Ministry of Lands to settle as many squatters as he could, having come to the realization that government can be ‘exploited’ for greater good. ‘‘When you are creative in government and there is political will from the top – I had Kibaki’s blessings – and you personally commit yourself to not engage in corruption, then the focus comes naturally,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘But if you are self serving, you cannot achieve much because you spend most of your time distracted elsewhere.’’

And yet the sole reason why Kibwana had joined politics was to push for constitutional change.

In 2005, elements within Kibaki’s government blew the pursuit of a new constitution up by attempting to shove down the country’s throat an unpopular and watered down version of the draft constitution produced by the national constituent assembly sitting at the Bomas of Kenya. Kibwana was caught in a Catch 22 situation, whether to walk out with mutinying ministers who were protesting the assault of the Bomas Draft or stay and see if anything was salvageable. ‘‘I had worked with Kibaki throughout the various opposition initiatives in the ‘90s,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘and in 2002 I was convinced he would stay true to the ideals we had all fought for considering the collegial manner in which he had come to power.’’ Kibwana gave Kibaki the benefit of the doubt. Kibaki lost the 2005 referendum. Kibwana lost the 2007 parliamentary election.

And as Kenya was burning as a consequence of the disputed 2007 presidential election, Kibaki called on Kibwana, who worked behind the scenes during the Koffi Annan led mediation at the Nairobi Serena. Thereafter, Kibaki appointed Kibwana to be the Presidential Advisor on Constitutional, Parliamentary and Youth Affairs at the Office of the President. Kibwana may have slacked during the 2005 referendum and paid by losing his seat. He was now back in the play.

‘‘Being an advisor,’’ Kibwana says of the period which yielded the 2010 Constitution, ‘‘all I did was give my two cents worth and left it at that. I didn’t have the latitude to go out there and take credit for the things my counsel resulted in, but as Joint Secretaries for Coalition Affairs, Miguna Miguna and myself were in the room when a lot of important decisions were made.’’

Kibwana concedes that what eventually became the Constitution of Kenya 2010 wasn’t exactly what he and others had envisioned, but after the political class retreated to Naivasha under the joint chairmanship of William Ruto representing Raila Odinga’s ODM and Uhuru Kenyatta for Mwai Kibaki’s PNU, the resultant harmomized draft was what the country had to work with. The big boys of Kenyan politics had reached a compromise and no one was to stand in their way. And so much as Kibwana was desirous of a third tier of government to come in between the national and county governments so as to make devolution more impactful resource-wise – to copy Nigeria’s 36 states and South Africa’s 9 provinces – he fell in line in support.

‘‘The thing that tickled me the most was that when you looked at photos from the promulgation event on 27 August 2010,’’ Kibwana says with a laugh, ‘‘it is the people who had all along been against a new constitutional order who are seated at the front, while those who fought street battles in support – at least those who could make it to the event – were seated at the back. We didn’t mind that those who had said a new constitution could only come over their dead bodies were there celebrating. We were at peace as long as the country had a new constitution.’’

At that point, Kibwana was ready to call it a day, imagining it was mission accomplished.

‘‘I was very happy that eventually this personal life long journey with a lot of comrades who had been killed, arrested, tortured and so on, had come to fruition,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘I felt fulfilled, and felt that even if that was the end of my public career then it was a rather good ending.’’

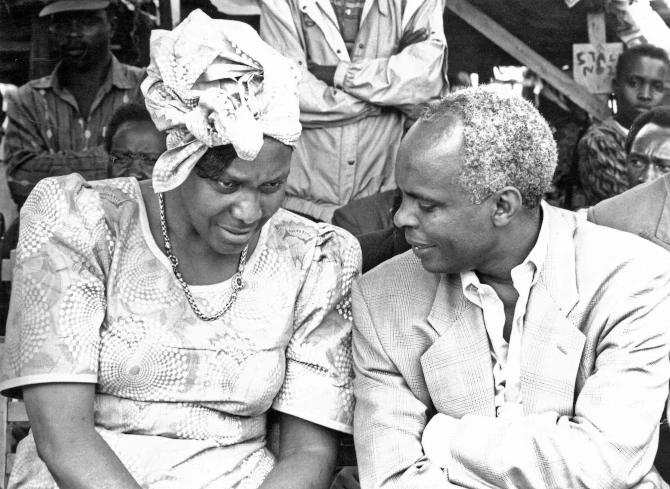

But then there was the little matter of the late Ndanze, Kibwana’s pauper aunt who raised him.

‘‘The reason I went to Makueni was because I remembered growing up there, seeing my aunt Ndanze and what we went through,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘I saw a window which was that the next stage of implementation was the county, going to the grassroots and making the constitution work. When we were agitating for a new constitution, we said we wanted a people driven process, a Wanjiku constitution, and so my idea of devolution was that it was Wanjiku driven.’’

Those were Kibwana’s ideas. In Makueni, Members of the County Assembly thought differently.

When Kibwana set out budgeting for the initial 5 billion sent to Makueni, MCAs asked for a fifth of the amount to cover themselves and their staff, jointly totalling about 100 individuals. The remaining 4 billion was to cover Makueni’s 1 million inhabitants, as well as cater for operational and other county government costs. Kibwana laughed and said no. He thought the MCAs were joking. The MCAs too laughed, believing Kibwana was joking. Jokes were flying across Makueni.

‘‘You know Governor,’’ the MCAs’ emissary told Kibwana, ‘‘let me help you. We can make your work be very easy. When you want something minor done, like you want us to help you pull crowds, all you’ll have to do is give us ka-vovyaa, about 5,000 shillings each. It’s like cooling off hot porridge or tea. But then when you want to do something not so minor, like maybe get us to vouch for you when donors come around, all you’ll have to do is give us ki-vovyaa, about 10,000 shillings each. And when you want to do a big thing, like pass a bill, you’ll then give us i-vovyaa, about 50,000 shillings to each.’’ Ka-vovyaa was small, ki-vovyaa was large, i-vovyaa was extra large.

Makueni had become a factory of jokes, but Kibwana wasn’t laughing. The MCAs told Kibwana unless he complied they wouldn’t pass the county budget. Both Kibwana and the MCAs stuck to their guns, and Makueni County was off to a false start. ‘‘I went to the people of Makueni and told them it was impossible for me to continue being their governor,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘because I could not do the things the MCAs were asking me to do. I also told the MCAs I was clearly in the wrong place because what they were asking of me wasn’t what I envisioned devolution to be.’’

A governing stalemate ensued. At one point, the MCAs passed the budget in March, three months before the end of the fiscal year. Kibwana couldn’t do any projects. Then the MCAs’ leader, the Speaker, instituted proceedings at the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) against top executives in Kibwana’s government, a move that caused administrative paralysis for almost two years. It later emerged that the allegations were false, and that perjury was committed. Then there was an attempt to impeach Kibwana, in which MPs from the fold of Kibwana’s political rival showed up with armed bodyguards who whipped out guns and fired shots, injuring a number of people including Kibwana’s Chief of Staff. Kibwana was ready to let it all go. It was at this point that the national government stepped in. President Uhuru Kenyatta appointed the Commission of Inquiry into the Dissolution of Makueni County, chaired by Mohammed Nyaoga.

‘‘I asked the people of Makueni to speak their minds to the Nyaoga Commission,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘and all they wanted was for the county to be dissolved so that we could all go back to the ballot. Reading the unfavourable writing on the wall, MCAs now started reaching out to me in the pretext of finding an amicable solution, but the horse had bolted.’’

The Nyaoga verdict, save for one dissenter, was that Makueni County should be dissolved. But when the report was presented to President Kenyatta, the Head of State reached out to the Council of Governors and expressed his reservations against the dissolution of Makueni. Much as the provision for dissolution is contained in law, Kenyatta was worried that it would set a dangerous precedent going forward, such that governors would become targets for blackmail. The President opted to spare Makueni, and Kibwana went back and explained the dynamics to the people. ‘‘They said they had understood, but that they would deal with the MCAs come the 2017 general election,’’ Kibwana says. And deal with the MCAs they did. The entire County Assembly of Makueni, save for one MCA, was voted out. Kibwana was popularly reelected.

‘‘Those first term challenges were a blessing in disguise because they helped us lay a solid anti-corruption foundation,’’ Kibwana says, ‘‘because from that point onwards, everyone including contractors knew that all one needed to do was to do their job and get paid, and that the Governor will not send someone to come and ask for a kickback. And if someone gave out a kickback and the county found out, then we would blacklist them. It was that simple.’’

This was then followed by the creation of what Kibwana calls the People’s Government.

‘‘We have 3643 villages in Makueni, and so we decided there will be a government at that level, which is where budgeting starts,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘The people at the village have a forum, through which they say what projects they want, and after identifying the project they elect a representative Project Management Committee (PMC), which then oversees the project to its completion. And if the PMC isn’t satisfied with a contractor’s work, then they don’t get paid.’’

Kibwana says that initially, some contractors imagined that these were simply a bunch of clueless villagers, until the PMC verdicts started affecting their pockets. The magic of the PMCs lies in their composition, Kibwana says, where they have experienced retirees, representatives from the religious sector, local professionals such as teachers, the youth, and others. But before letting the PMCs get down to work, Kibwana led a series of trainings, including empowering committee members to competently read Bills of Quantities in construction projects. If it says the project needs 100 bags of cement, the PMC will be there to count, so that as much as the county’s technical staff are oversighting, the locals too keep their eyes open. From that point onwards, the county government had a complementary twin in the People’s Government.

I ask Kibwana whether this was his own invention. He says no. It is in the law. Which law?

‘‘Article 1 of the constitution says the people are the sovereigns, and so they merely donate their power to we their leaders,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘And when you go further, there are provisions for public participation and people’s economic rights. Of course I have found creative ways of expressing these provisions to the extent that the people benefit the most from them.’’

From the 3643 villages, the next structure of the People’s Government is Village Clusters, each of which is made up of about 10 villages. In total, Makueni has 377 Village Clusters, which work in the same way as the village committees when it comes to budgeting and oversight. It is at the Village Cluster level where bursaries are disbursed, alongside an interest free credit facility called Teleka. Here, everyone knows everyone and vouching happens communally. From the Village Cluster one goes up the ladder to 60 Sub-Wards, where final decisions are made, after which are the 30 Wards then 6 Sub-Counties. Kibwana says Makueni’s Ward Development Fund stands at 33 million shillings today, and that Makueni has allocated a second budget to the Village Clusters, which decide which projects need urgent attention and spend the money on.

The rule is that once the People’s Government has ratified a project, Kibwana and deputy governor Adelina Mwau sign on the dotted line, and the County Assembly has no choice but to approve the people’s wishes. Otherwise, if the MCAs attempt to subvert the people’s will, then they’ll have to ready themselves to face the people’s wrath come election time. It is a soft form of the dictatorship of the proletariat, where even Kibwana himself isn’t spared. ‘‘The people usually tell me that Governor, even you if you misbehave,’’ Kibwana says with a chuckle, ‘‘we shall walk to your mother and ask her what kind of son is this you raised for us?’’

It is this people-centered approach, Kibwana says, that has resulted in Makueni being one of the first if not the first counties to have universal healthcare, with individuals making an annual contribution of 500 shillings, while those over 65 are exempted from making the contribution. It was also the people’s idea for Makueni to have value-addition facilities for milk, mangoes and green grams. I ask Kibwana how such a model is sustainable, and he tells me this system of governance is in the blood of the people of Makueni, and it will be near impossible for anyone to try and reverse it. But be that as it may, the County Assembly is passing as many relevant laws as possible so as to secure a lot of the gains already made. The people are clearly winning.

For now, Kibwana wants to invite an external evaluator, so that he has an independently done report to hand over to his successor when the time comes, as Kibwana hopefully changes address from Villa Makueni in the Wote hills and planes to the serenity of State House Nairobi.

And now the big question. Does Kivutha Kibwana really want to be president?

‘‘Yes, and this candidature runs until 9 August 2022,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘You know Moi used to say some things and we used to think he didn’t know what he was saying. Like when he used to say KANU will rule Kenya for 100 years. He may not have meant KANU the party, but he definitely meant KANU the people, those he had groomed, and the country has been beholden to them so that it is an anomaly when someone else, someone even more competent and suited for the job shows up in the scene. But if you look at these individuals, most of whom have been in cabinet or top leadership since the ‘80s, what have they done? What new thing will they do?’’

To Kibwana, this is not about him.

‘‘This is a candidature of the people of Kenya, the people’s candidature, not my own,’’ Kibwana says. ‘‘It is a candidature where everybody matters, where everybody will be mobilized for the renewal of our country. I believe the people will see the honesty, sincerity and genuineness.’’

For Kibwana, his pitch is simple. He has taught law at the university for 25 years – having taught Kenya’s Attorney Generals and Supreme Court justices; he has been in the streets fighting for Kenya’s second liberation for decades; he has been an MP, a Minister, a presidential advisor – Kibwana excuses his time serving the Kibaki government, saying there is consensus that this was the only government since independence that made an attempt to impact the people’s lives for the better – and been a governor, leading the most benchmarked county in Kenya. And now, he feels it’s time he brought all of this wrapped up in one person carrying the aspirations of 45-plus million hopefuls, as he seeks to replicate Makueni at the national stage and bring a new ethos.

I ask Mutunga what he makes of Kibwana’s performance in Makueni.

‘‘Kibwana’s leadership as Governor of Makueni has been praised by most if not by all. In my view, he has breathed life into the implementation of the Constitution in various areas: participation of the people to express their sovereignty; sharing of political power right to the grassroots; Makueni becoming a beacon of how devolution should work; mass civic education; zero tolerance to corruption; implementation of rights, values, transparency, and accountability by the county, the county has done well in various pro-people projects such as University scholarships, universal health care; and embryonic industrial pursuits,’’ Mutunga says, and goes on. ‘‘He has been a great example of how political leadership can serve the masses in a humble and honest manner. Makueni has shown how the imagination of a people can be captured to believe that progress and transformation is possible.’’

And what does Mutunga think of Kibwana’s presidential bid? Is Kibwana 25 years late since 1997 when he was the political opposition’s compromise candidate for the presidency aged 43?

‘‘Kibwana’s bid can have a lasting legacy if he is the first presidential candidate to denounce and condemn the politics of division in Kenya; to denounce and condemn the baronial narrative of organizing politics of division that has been with us for the last 58 years; and defining what he means by united front of like minded political parties,’’ Mutunga says. ‘‘This last point is critical because he has not talked of progressive political parties, which in my books must disengage from the baronial factions that occupy the political space at the moment. 2022 should, in my view, be about this movement capturing the imagination of Kenyans, where the mass grave for the baronial politics should be dug and the burials must start in 2022 going forward.’’

And finally, what’s for all intents and purposes an endorsement.

‘‘Here is a man who can lead a serious project of transformation of the Motherland with a unique strong will that belies his humble, modest, and peasant-intellectual personality,’’ Mutunga says of his one time student, colleague, comrade, and potential future president. ‘‘I believe that under his presidency, the robust politics of issues will be born.’’

The teacher and the student have spoken.

…

This project is a collaboration between

Debunk Media and the Star Newspaper.