For two general elections, Moses Masika Wetangula has been one of four principals in the main opposition coalition, and is now a principal a third time, hoping his coalition will ascend to state power. To Wetangula, being a principal is good political arithmetics, since whoever becomes president is only a first among equals, and he hopes that if not now, then one day his turn to become a first shall come. In this three-part read, journalist and Debunk Media’s Editor-in-Chief Isaac Otidi Amuke goes back to his two-hour conversation with Wetangula, in which he examines the Bungoma Senator’s tenacity and staying power, and what his presidency – if and when he becomes a first – will look like and mean for Kenya.

Part 1: From Meek Catholic Boy To Gutsy Rookie Advocate

When Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka and his batch of Kenya Airforce accomplices – Pancras Oteyo Okumu, Joseph Ogidi Obuon, Charles Owira, Walter Odira Ojode and Bramwel Injeni Njereman set out to overthrow the four year old government of President Daniel arap Moi on 1 August 1982, they weren’t aware that the coup d’état would abort, after which they would flee to neighboring Tanzania where they would get betrayed and handed over to Kenya to face court martial, in which instance no advocate would agree to defend them.

As the mutiny unravelled and got foiled, 26 year old Moses Masika Wetangula was similarly unaware of just how much the events of the day would shape his personal and professional lives. As a curfew was enforced to deal with remnants and aftershocks of the insurgency, Wetangula and his classmates at the Kenya School of Law (KSL) on Valley Road got locked up for two weeks at Groven Hotel, which was located opposite present-day CITAM Valley Road, and whose exact location is part of the Department of Defense headquarters today.

Save for a last minute expulsion from Friends School Kamusinga just two months shy of his sitting for his A Level finals on what he terms flimsy grounds – he was accused of inciting students against the head teacher, Wetangula had had an otherwise pious-looking Catholic upbringing, such that mentioning his name and the word coup in the same sentence would seem like a rich stretch of one’s imagination, whatever context the word coup would be used in.

Growing up in a cordially co-existing polygamous family of 30, it was imperative that from an early age, Wetangula had to learn to get ahead of the curve one way or another. 15 children were born to his mother, comprising four sets of twins and seven singles. Wetangula, who was the fourth born, was one of the singles alongside his baby brother Tim, the MP for Westlands.

Coming after an elder sister who passed on young, followed by a twin brother and sister, followed by yet another sister who succumbed young, Wetangula was the de facto firstborn in the homestead, considering the twin brother was being groomed to become a priest and was enrolled in a seminary, while the twin sister was sent to boarding school pretty early.

‘‘I started school in 1964 aged 8 years old when I joined Nalondo Primary School,’’ Wetangula says when we speak at the wide gazebo at his humongous Karen home. From where we sit, at the back of the single storey residence, one encounters a well manicured lawn almost the size of a soccer pitch, littered with palm trees. On one end of the compound is a long driveway leading to the main entrance of the house, where one finds a stretching garage for three and an elongated eco-friendly carport which can hold up to about a dozen vehicles. And when one follows the driveway back-out, it leads into a second half of the property, a banana plantation. The other flank of the home has above-average-sized guestwings, servants and boys’ quarters.

A swimming pool is cooling off next to us. We’re stationed not too far from the kitchen.

From Wetangula’s home in Mukhweya village in Bungoma, Nalondo was about 5 kilometres away, not the closest school. A kilometer away was Namilama DEB Primary School, but because it wasn’t Catholic, Wetangula had to brave the distance to the Catholic Nalondo.

‘‘Due to the huge distances between homes, and because of roaming wild animals – I could hear hyenas laugh on my way to school,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘we had to go to school as a group with other children from the neighbourhood.’’

But what would happen if one couldn’t meet the rest of the kids on time?

‘‘My mother would hear none of it,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘you’d have to walk to school alone.’’

It is in the spirit of moving as a pack that Wetangula’s mother ordered that as much as lower primary kids were released from school at noon, Wetangula had to stay in school and come home after 4pm when the rest of the school left for home. This way, he would get more time to study, before getting lost in picking coffee or weeding maize, depending on the season.

And yet, walking 5 kilometers to Nalondo must’ve been preparing Wetangula for the future.

‘‘I used to walk for 30 kilometers daily,’’ Wetangula says of his early days in high school, ‘‘on the road from Mukhweya through Namilama, Malinda, Chwele, Chebukaka to Teremi,’’

Ideally, Wetangula would have found a place at Friends School Kamusinga for his form one, but unfortunately, much as he had excelled in his Certificate of Primary Education, his head teacher at Nalondo failed to submit the candidates’ school selections on time, leaving them in post-exam limbo. This is how Wetangula did his first year at Busakala Secondary School, before an uncle adopted him and took him to the better-performing Teremi High School, where Wetangula agreed to repeat Form One as a prerequisite for admission. Unfortunately, his uncle could only afford the tuition fees of Ksh. 450, meaning he had to be a day scholar.

Teremi was 15 kilometers away from Wetangula’s home.

‘‘There was a bus company called Mawingo,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and there was a driver called Bakari who drove one of the buses on the Bungoma-Kitale route. He used to see me walking along the road every single weekday with my school bag, until one day he stopped the bus.’’

Bakari: Young man, where do you go every morning? I see you carrying a school bag.

Wetangula: I go to Teremi.

Bakari: You go that far on foot?

Wetangula: Yes.

Bakari: From now on I will be giving you a lift to school.

That particular Mawingo bus used to pass by Wetangula’s Mukhweya home at 6.30am, and by 7am Wetangula would be at Teremi. Bakari eventually took Wetangula to meet the owner of Mawingo, an Arab man called Abdul Karim, to whom Bakari presented Wetangula’s case. Abdul gave Wetangula a bus pass which he used everyday for 3 years. Considering the last bus from Kitale to Bungoma passed Teremi at 4pm, Wetangula skipped games to catch the bus.

‘‘When I got to Form Four I told my uncle I needed to be in boarding school,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He agreed to pay the boarding fees of Ksh. 150. Unfortunately, once again the head teacher didn’t forward our school choices on time, leaving us stranded with excellent results.’’

Luckily for Wetangula, his uncle reached out to Kamusinga and he was offered A Level placement.

At Kamusinga, Wetangula was classmates with former Cabinet Secretary for Health Cleopa Mailu and former Webuye MP Saulo Busolo. It was here that he got the opportunity to play sports, forming part of the Kamusinga soccer team which won the national championship. It was also here that Wetangula got fascinated by the likes of James Orengo and Oki Ooko Ombaka, who had both been student leaders and turned out to be firebrand lawyers.

He, too, had to become a lawyer.

It was in possibly getting ahead of himself as a wannabe lawyer that Wetangula took to speaking at the school Kamukunji with a little more gusto than had been the practice, a slippery slope which resulted in his expulsion alongside his two Form Six classmates, Peter Masengeli and Martin Rodgers Mutende. They had to be given police escort as they sat for their A Levels. This was the first time Wetangula was going against established order.

‘‘I was so confident I would become a lawyer, so much so that when I was picking my three degree courses,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘I put law as my first, second and third choice.’’

Wetangula survived the expulsion, making the cut for the Faculty of Law at the University of Nairobi. Here, other than playing soccer with the likes of JJ Masiga, Wetangula’s life was largely lived on the straight and narrow alongside members of the infamous class of 1981 which included National Assembly Speaker Justin Muturi – who was Wetangula’s first year roommate, Justice Mohammed Ibrahim of the Supreme Court, Justices Fatuma Sichale and Jessie Lessit of the Court of Appeal, Justices Boaz Olago, Aggrey Muchelule, Fred Ochieng, Joseph Karanja, Roselyn Wendo, Martin Muya and Kaburu Bauni of the High Court, former Ministry of Lands PS Dorothy Angote, Federation of Kenya Employers executive director Jacqueline Mugo and former High Court registrars Jacob ole Kipury and Charles Njai.

After graduating in October 1981, Wetangula joined the Kenya School of Law (KSL), where the coup found him. Aside from the coup, the year at the KSL flew past quickly and uneventfully.

The group exited the KSL in October 1982.

What followed was Wetangula’s chaotic albeit brief judicial stint. First sent to Nakuru as a District Magistrate 2 – where he could hear between four to five matters a day – Wetangula was quickly dispatched to Kithimani in Machakos, where ‘‘there was no work. You could stay for a week to handle one or two cases, with the courtroom located behind a shop.’’ After complaining to the judicial honchos in Nairobi, Wetangula was transferred to Kisii, where he found an overload of magistrates, from where he was sent to Rongo. It was February 1983.

‘‘My father had decided, and decreed, that I take responsibility for educating all my siblings,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘I decided that to be able to shoulder the huge responsibility bestowed upon me, I had to look for better ways of making ends meet. I resigned as a magistrate.’’

Wetangula arrived in Nairobi with nothing but Ksh. 2,400, his last salary as a magistrate.

Luckily, David Malakwin, Wetangula’s classmate from the University of Nairobi, had gotten employed by the Kenya Posts and Telecommunications Corporation (KPTC), and was given a three bedroom staff house at the junction of Ole Odume Road and Ngong’ Road. Malakwin invited Wetangula over, alongside their other classmate and future registrar of the High Court, David ole Kipury, who was working as a magistrate in Nairobi. Malakwin, Wetangula and ole Kipury each took a bedroom, with Wetangula and ole Kipury contributing 500 bob each to go towards water and electricity. Food was bought jointly by the trio.

‘‘We lived very well together,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘until such a time when we each decided to move out and start our own families.’’

For work, Wetangula found a similar quid pro quo arrangement.

Murtaza Jaffer – who became one of the founders of Kituo cha Sheria and a judge at the industrial court – had an office on Luthuli Avenue, next to Ramogi Studio. Like Malakwin, Jaffer invited Wetangula and Wetangula’s classmate and future Supreme Court Justice Mohamed Ibrahim to share his office, only that they wouldn’t pay for their tenancy in cash.

‘‘Jaffer had a lot of trade union work,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and so the arrangement was that we do his work in court for no payment, and share his offices for no payment as well.’’

It was around this time that Wetangula received the Ochuka brief from a senior politician, who he declines to name for now, for potentially obvious reasons.

‘‘I happen to know that rounds were made across the chambers of notable advocates, those considered established enough to not be wary of the Moi state,’’ Wetangula says of the hunt for counsel to represent Ochuka and others. ‘‘All of them gave the brief a wide berth.’’

At the time, Kenya was a de jure one party state, and following the attempted coup, an injured and emboldened President Moi had issued an infamous warning to the plotters and their real or imagined sympathizers, ‘‘nitawawinda kama panya mpaka kwa mashimo.’’ A flurry of house arrests and detentions without trial were to follow as Moi firmed up his grip on state power.

‘‘I will not say who my instructing client was, but a very senior politician sent for me, and asked me if I could take up the cases,” Wetangula says. “Considering the trials could result in a death sentence, the military was also obligated under the law to ensure all the accused had legal representation. This too was a factor in my accepting the brief.’’

Everyone thought Wetangula was insane.

‘‘My father was very frightened,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He jumped on a bus, came to Nairobi and came to my office. His instruction was, ‘‘Leave these cases alone. You are going to bring problems to yourself and to the family.’’ I told him Daddy I won’t leave the cases because I know I am doing the right thing and history will absolve me. I asked him to go back home to the village and not talk about the cases to anyone because he knew nothing about the brief.’’

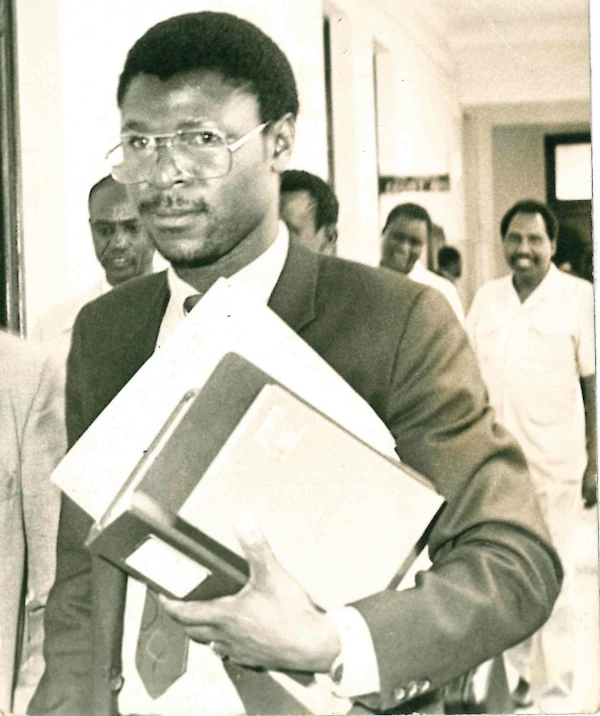

As the cases got underway at court martial at Langata Army Barracks, Wetangula’s notoriety within the legal fraternity went through the roof.

Who was this crazy enough kid representing mutineers at such a dicey time?

‘‘Byron Georgiadis, a very accomplished criminal defense lawyer from Kaplan and Stratton invited me to lunch and gave me a lot of guidance,” Wetangula says of the attention the cases started attracting his way as his seniors took notice. “He told me, ‘‘When you cross examine a witness – and I know you do it in your own way – you must punch. You must leave a positive impression on the court, because at the end of the day when facts are borderline, the hunch you create has a bearing on the judge or magistrate, because they too exercise discretion.’’’’

After his clients were sent to the gallows by the court martial, Wetangula, now joined by George Oraro, rushed to the High Court to appeal. Here, they won some and had the men set free, and lost some, resulting in Ochuka, Oteyo, Njereman and Ojode facing the hangman’s noose. There was no room for proceeding to the Court of Appeal.

It was game over for the soldiers.

I ask Wetangula why he took the cases.

‘‘When we were being admitted to the bar before Chief Justice C.B. Madan – and this is advise we were also given by Pheroze Nowrojee when he was teaching us at the School of Law,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘he said once you are in the calling as a lawyer and become an advocate, you always act without fear or favour because you don’t represent what your client did. You represent the rights of your client. If they are coup plotters, you are not part of the coup.’’

As fate would have it, almost immediately, Wetangula became first-name-basis friends and acquaintances with the likes of Fred Ojiambo, Amos Wako, Lee Muthoga, Richard Otieno Kwach, Joe Okwach (deceased), E.T. Gaturu, among other notables within the profession.

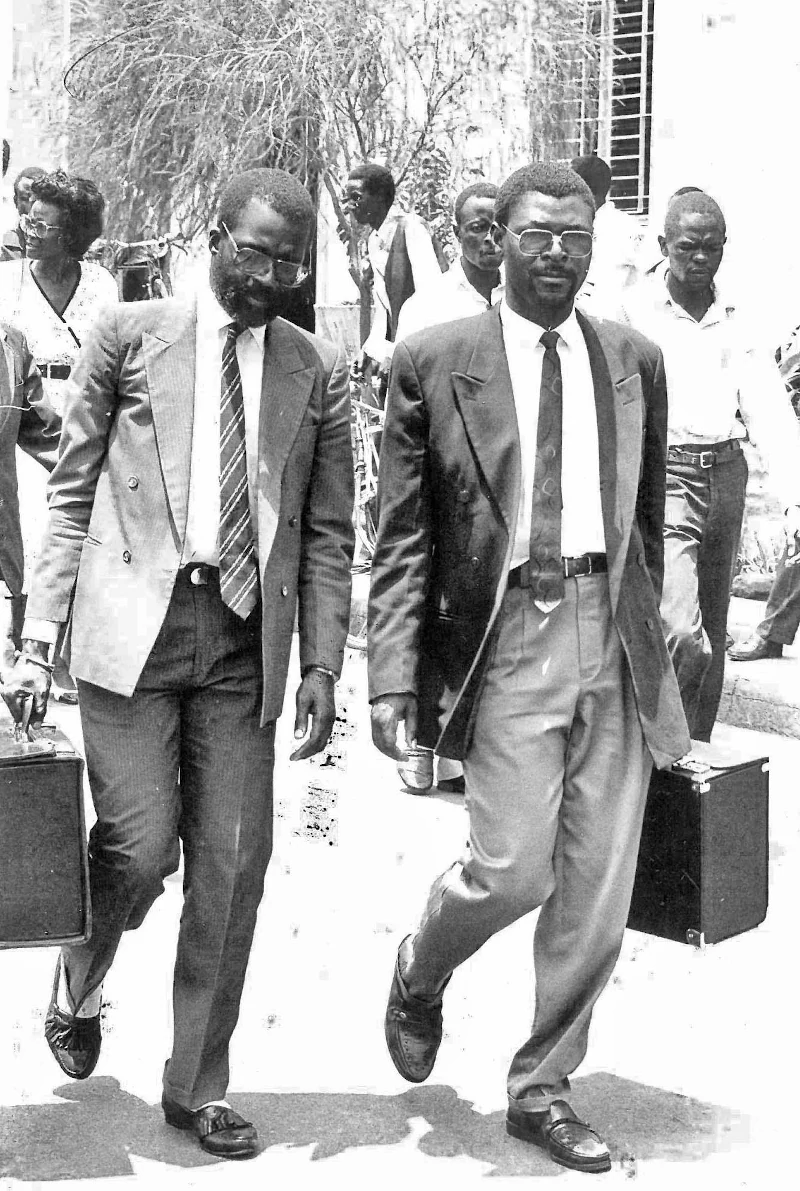

‘‘Senior lawyers with half-moon glasses were in their 50s,’’ Wetangula says with a tinge of pride as he speaks of some of his newly acquired friends after he was done defending the coup plotters. ‘‘They walked into courtrooms with their hands draped at the back of their coats, with somebody carrying their books, another person carrying their wigs, someone else carrying their gowns. But here I was, a young man gliding past them going to court.’’

At barely 30, Moses Masika Wetangula had arrived, legally speaking.

Part 2: The President’s on the Line and Other Short Stories

Before January 1993, Moses Masika Wetangula had never met President Daniel arap Moi.

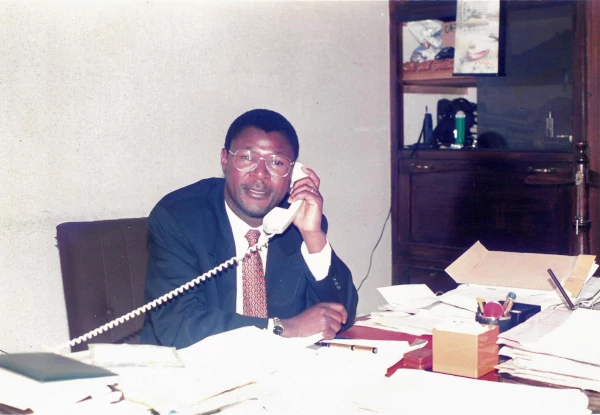

By this time, ten years after Wetangula represented the 1982 coup plotters, the man’s stature had grown in leaps and bounds. Wetangula and Company Advocates had since moved from Luthuli Avenue – in the midst of what Wetangula calls 24 hour disco noise, and crossed Moi Avenue, first settling at Hughes Building on Kenyatta Avenue, then to Queensway House on Mama Ngina Street, before taking tenancy at Corner House, a most prestigious address at the time located at the junction of Mama Ngina Street and Kimathi Street. The skyscraper had practices run by the likes of Mutula Kilonzo, who was the President’s lawyer, and Wetangula’s university classmate Fatuma Sichale, among a dozen other top law firms. Wetagula’s client portfolio had similarly fattened to include blue chip companies and state corporations.

At that juncture, according to Wetangula, running for office was the last thing on his mind.

But something else had happened.

In December 1991, Moi had capitulated and agreed to repeal Section 2(a) of the Constitution, allowing for multipartyism. It was the outcome of the subsequent 29 December 1992 general election – which Wetangula hadn’t participated in – that changed the course of Wetangula’s life.

‘‘A very vibrant, fearless and articulate team of young politicians were elected to Parliament,’’ Wetangula says and lists some of their names, ‘‘Paul Muite, Martha Karua, James Orengo, Anyang’ Nyong’o, Mukhisa Kituyi, Kiraitu Murungi, and many others.’’

This was good news for Kenya.

The bad news, especially for the ruling party KANU, was that these were all opposition MPs.

KANU and Moi had a headache, to which they found a solution.

‘‘I had always stuck to a routine of reporting to my office at 6am and never leaving before 7pm,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘And so one evening as I was seeing a client at 7pm, my then long serving secretary Jessica Olinga rushed in and told me there was somebody on the line called Moi.’’

Jessica: He says his name is Moi.

Wetangula: Go and tell him I am meeting a client. I will call him back.

Jessica: I will not talk to him. I think it is the President. You have to come and talk to him.

Wetangula went and picked the call. And true to Jessica’s word, it was President Moi.

Wetangula: Hello?

Moi: How are you Moses?

Wetangula: I am fine Your Excellency.

Moi: Congratulations!

Wetangula: What have I done Your Excellency?

Moi: You have been nominated to Parliament.

‘‘You have seen who has been elected,’’ Moi told Wetangula, referring to the formidable and troublesome opposition. ‘‘I want you to be part of the team that will help my party and my government. I have picked you because of your courage. Give me your best as your President.’’

Moi had one more request.

‘‘I want you to be part of the Speaker’s Panel,’’ he said, ‘‘to keep Parliament under control.’’

Being a member of the Speaker’s Panel was akin to being a temporary Deputy Speaker, meaning Moi was looking to commandeer the multiparty Parliament in whichever little ways he could.

The following morning, Wetangula was invited to State House Nairobi alongside J.J. Kamotho and G.G. Kariuki, both of whom had lost elections and had been nominated. The other KANU nominees were Wilson Ndolo Ayah and Ziporrah Kittony. Also present were Elijah Mwangale – who had just lost to Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi, Attorney General Amos Wako, Vice President Prof. George Saitoti, Nicholas Biwott and State House Comptroller Franklin Bett, Wetangula’s contemporary.

From that point onwards, Wetangula became part and parcel of the KANU and Moi machinery.

But be that as it may, Wetangula, in his own admission, faced a daunting existential crisis.

Bungoma, the place where he came from, was solidly an opposition stronghold, with members of the Bukusu community having fallen in line to the last man in support of FORD Kenya, even after the death of their patriarch Pius Henry Masinde Muliro. Michael Kijana Wamalwa had been elected FORD Kenya’s second vice chairman in 1992, and became Muliro’s undisputed heir.

‘‘I had to find a way to delicately navigate between the interests of my friend Kijana Wamalwa, who was in the opposition but with whom we came from the same stock,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and those of President Moi, who had nominated me to Parliament.’’

This balancing act of trying to please Moi and not harm Wamalwa is what turned Wetangula’s nomination into a curse and a blessing; a blessing because it launched his political career, a curse since to his critics, working for Moi at a time when the entirety of Bungoma was against the man had elements of betrayal, a sort of blemish which Wetangula contends with to date.

‘‘After my handling of the 1982 cases, Wamalwa came to see me, curious about who I was,’’ Wetangula says of his private friendship with one of the opposition’s shining lights. ‘‘We built a friendship from that point onwards, and being avid readers, whenever either of us travelled abroad we brought each other books. And even when I was a KANU nominee, he’d come to my chambers and do his private calls and emails whenever he needed an escape from his office.’’

Wetangula was to pay a price for his 1992 choices during the 1997 general election.

Still keen on remaining useful to Moi, Wetangula threw in his lot with KANU when he sought the Sirisia Constituency parliamentary seat, at the time held by his teacher at Friends School Kamusinga, FORD Kenya’s John Munyasia. Munyasia’s superpower was that he was as gifted an orator as the rest of the FORD Kenya hotbloods, so that there was a joke that if one had beef with Munyasia, then the biggest mistake they could make was to allow Munyasia to open his mouth, because the moment he started speaking, you’d forget you were feuding with him.

Among the Bukusu, Masinde Muliro had built a tradition of asking the electorate not to merely elect representatives, but to instead elect warriors who would form part of his battalion at the national stage. To pass this message, Muliro would summon the triumphalist spirits of Bukusu warriors of yore, especially those who won the infamous Naitiri War, a cluster of fighters who were simply referred to as Naitirian. And so as he moved from one constituency to the next, Muliro would tell voters he only wanted them to elect leaders of the Naitirian calibre – nenya Naitirian, he would say, I only want Naitirian – and this would be code for the electorate to vote for whichever candidate Muliro endorsed. Michael Kijana Wamalwa inherited Muliro’s rule book.

And so as Wetangula campaigned in Sirisia on a KANU ticket, Kijana Wamalwa swept the rest of Bungoma and Trans Nzoia asking the electorate to only give him warriors of the Naitirian kind, all of whom had to be FORD Kenya candidates. The electorate listened and acted accordingly.

‘‘It was probably out of my friendship with Wamalwa that much as he went round campaigning for FORD Kenya candidates, he deliberately skipped coming to Sirisia to campaign for Munyasia, possibly in a bid to spare me the effects of his influence,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘There is no doubt that Munyasia felt shortchanged by Wamalwa’s act of tactically avoiding to campaign in Sirisia.’’

Even so, Wetangula still lost to Munyasia. The anti-Moi wave was impossible to mitigate.

After the electoral loss, Wetangula went to see Moi.

‘‘Young man,’’ Moi told Wetangula, ‘‘all politics is local. If you’d have sought my advice before running, I’d have encouraged you to go and join Wamalwa, run on FORD Kenya and win. If you’d have won, then I would have had a friend in the opposition, and I am sure when the chips are down you’d have stood with and by me.’’

It is a piece of advice Wetangula has never forgotten, and never hesitates to dish out.

And with that, Moi appointed Wetangula as the inaugural chairman of the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC), which has since become the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA), where he served for two and a half years before resigning to focus on Sirisia politics.

This time round, Wetangula implemented Moi’s advice religiously.

‘‘By the time we were getting to the 2002 general election,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘I was fully in Kijana Wamalwa’s fold, both as his personal lawyer and the party’s lawyer. I went for party nominations with Munyasia and defeated him, and had such an easy sail to Parliament.’’

Mwai Kibaki won the presidency, with Kijana Wamalwa as his Vice President.

As agreed upon during the pre-election phase, leaders of the conglomerate of political parties which had powered Kibaki’s ascension to the presidency submitted names of their preferred representatives in the Cabinet. Wetangula strongly believes Wamalwa submitted his name as part of the FORD Kenya list, but then Kibaki neither stuck to FORD Kenya’s nor did he adhere to the proposals given by the other coalition partners. Wetangula was left out.

‘’In July 2003, a year after taking government,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘Mwai Kibaki called me and told me he wanted to appoint me as his assistant minister for Foreign Affairs. I accepted the offer. I believe it was Wamalwa who kept pressuring him to appoint me as originally intended.’’

Michael Kijana Wamalwa died two months later, at a time when Wetangula’s metamorphosis from KANU’s cockerel to FORD Kenya’s lion seemed complete.

When Masinde Muliro died in August 1992, the order of succession within FORD Kenya and by extension his Bukusu constituency was uncomplicated. Mukhisa Kituyi, who was a leading light in the party, conceded on grounds that he was young. Musikari Kombo, who was one of Muliro’s right hand men and a key financier, gave way to his senior. Michael Kijana Wamalwa stepped into the role with the full blessings of those who had coalesced around Muliro and FORD Kenya.

However, Wamalwa’s succession wasn’t as seamless.

Mukhisa Kituyi, Musikari Kombo and Noah Wekesa each wanted to lead the party. Wetangula, who was still making inroads within the FORD Kenya fraternity, supported Kombo with the promise that Kombo would hand over to him when the time was ripe. Kombo won the seat.

And yet, Musikari Kombo wasn’t Michael Kijana Wamalwa.

Where Wamalwa deployed charisma Kombo employed the slow motion counsel of the wise, and where Wamalwa was burning with ambition Kombo was handling Muliro’s legacy with velvet gloves, making it almost impossible for the party to roar. Soon, little uprisings fermented.

FORD Kenya’s currency had always been what Mukhisa Kituyi calls electricity – charged rhetoric delivered by a battery of hotheads coupled with an anti-establishment groundswell (unavoidable even if they were in government, like Wamalwa’s candid ‘I am afraid power has gotten into our heads’ speech delivered just before his demise). Kombo neither exhibited nor inspired any of these.

Seeing the electricity gap in FORD Kenya, Wetangula started plotting a takeover.

In the meantime, at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wetangula deputized Kalonzo Musyoka, a man he had first met in 1985. At the time, a by-election had been occasioned in Kitui North Constituency, and 32 year old Musyoka was throwing his hat in the ring. As a show of solidarity, a group of young lawyers got together to fundraise for Musyoka. Wetangula was among them, giving a worthy contribution of 500 bob. Then quickly came Chirau Ali Makwere as Minister of Foreign Affairs, before he was replaced by Wetangula’s favourite, Raphael Tuju.

‘‘Tuju treated me very well,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He gave me the latitude to act as if I was the substantive Minister for Foreign Affairs by sending me to represent Kenya in all manner of very high profile ministerial engagements, which in turn gave me huge exposure in multilateralism.’’

Unfortunately for Tuju, he lost the 2007 elections.

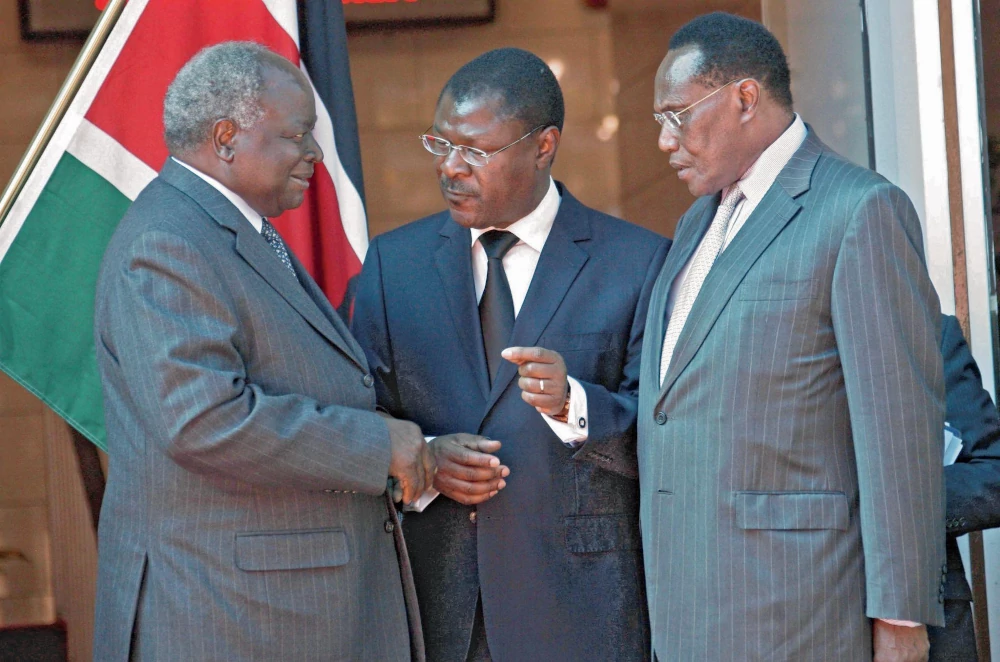

And as Kenya was burning following the 2007 presidential election dispute, Kibaki had to call on Wetangula’s institutional memory at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In fact, as Kibaki’s re-election was faltering in mid-2007, Wetangula and others had positioned themselves by getting together and engineering a re-election vehicle, the Party of National Unity, whose constitution was drafted at the chambers of Wetangula and Company Advocates by a group of lawyers including George Nyamweya.

‘‘As the chaos erupted, President Kibaki called me and dispatched me to Addis Ababa to address the African Union, with the aim of convincing the outside world that Kenya was on its way back to stability,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘However, as I addressed the AU plenary and assured them that Kenya was salvaging the situation, all international TV stations started beaming images of Naivasha burning. It was almost impossible to convince anyone that all was well back home.’’

Raila Odinga had sent Anyang’ Nyong’o to address the AU and counter Wetangula’s claims. But according to Wetangula, he used his AU connections to block Nyong’o’s address. It was while in Addis – and possibly as a reward for his loyalty to the Kibaki regime – that Wetangula received a phone call informing him that Kibaki had appointed him Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Wetangula tells me he used his connections to block Nyong’o’s address.

While in Addis, Wetangula received a phone call.

Kibaki had named him Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Still in Addis, Wetangula met with Jean Ping, the then Chairperson of the AU Commission, and convinced him to come to Kenya and speak to the warring parties. Ping jetted into Nairobi and embarked on talks with the two groups. Wetangula then advised Kibaki on the urgency of an Africa-led mediation process, to which Kibaki and his consigliere Francis Muthaura agreed to.

Wetangula was up in the skies again.

‘‘I flew to Accra to meet President John Kufuor, who was the Chairperson of the AU,” Wetangula says. ‘‘I found Kufuor was away in his private home in Kumasi, from where he sent his presidential jet to come pick me up. It was a 90 minute flight. I met Kufuor, briefed him, then made a call to President Kibaki. The two spoke, then Kufuor and I addressed the international press at his residence. Kufuor agreed to come to Kenya the following day after he and I had agreed to rope in Koffi Annan. I had also suggested that we bring in a regional leader, and so I flew to Tanzania and persuaded President Benjamin Mkapa. Lastly, we agreed to bring onboard Mama Graca Machel.’’

This was the precursor to the Serena Talks.

From there onwards, Wetangula took his rightful place in the Kibaki government. I ask Wetangula, now that he’s worked with Moi and Kibaki, what were they like?

I ask Wetangula, now that he’s worked closely with Moi and Kibaki, what they were like.

‘‘Moi and Kibaki were complete opposites,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘Mzee Moi enjoyed talking to everybody. You could even say he enjoyed listening to gossip, because you could sit at a lunch table at State House and people who liked gossiping and maligning others would be having a field day – Mzee unajua huyu, Mzee unajua yule, nini nini… – and he would listen to them. Sometimes he acted on whatever he heard, other times he didn’t. But he was very extroverted, and knew an individual by name in almost every village in Kenya.’’

It doesn’t stop there.

‘‘He liked going everywhere, he was not one to sit and let things happen,’’ Wetngula says of Moi. ‘‘He was hands on sometimes to the level of intrusion in the discretions of his appointees.’’

As if that wasn’t enough, Wetangula remembers that whenever one travelled with Moi – like that time Wetangula was invited to an official trip to Brussels – one was obligated to have a joint breakfast with him, a joint lunch with him and a joint dinner with him, as a delegation.

Kibaki was the reverse.

‘‘Mzee Kibaki is a person who kept to himself,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘As his assistant minister for four years and as his Minister for Foreign Affairs for another four years, I do not recall sharing a private meal with him, save for state banquets and post-cabinet lunches, where he rotated who sat next to him depending on who had issues which needed his attention.’’

And when the politics got heated, Wetangula remembers Kibaki calmly telling them that life was not about the people they liked but about the people they lived with, asking them to go find an amicable solution. And whenever ministers came to brief him, Kibaki listened and if he was satisfied, thanked them and let them go. Or if he had further queries or suggestions, Kibaki shared them then left the matters at that. There was no room for gossip.

‘‘And whenever we travelled out of the country for official State business,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘Kibaki stayed in his room, came out for meetings and retreated back to his room.’’

To his mind, Wetangula believes he represents the best of Moi and Kibaki.

‘‘And this makes me the better person,’’ he says.

Part 3: Get Thee a Seat at the Table, and the Rest Shall Follow

Mukhisa Kituyi tells a story of how after Masinde Muliro’s death and FORD was splintering into what were to become FORD Kenya and FORD Asili, Michael Kijana Wamalwa, who had taken the mantle to lead Muliro-orphans, was undecided as to whether to go the Jaramogi Oginga Odinga or Kenneth Matiba route. That stalemate, according to Kituyi, was resolved by a section of the Bukusu elite which had organized itself into a brain trust first for Muliro then Wamalwa. Joining Kituyi and other Young Turks, the professionals pushed Wamalwa to go the Jaramogi way.

Much as this was a political decision, it had cultural and spiritual significance.

In a widely quoted prophesy, the Bukusu freedom fighter and leader of the Dini Ya Musambwa Elijah Masinde wa Nameme spoke just three words, bubwami bukhamile khunyanja – leadership shall come through/from the lake. The implication of these words was that for someone of Bukusu origin to lead Kenya, they had to work closely with inhabitants of the Lake Victoria area – estimated to be the Luo, who would then make Bukusu leadership materialize.

It may be easy to dismiss Masinde’s prophecy, but to those who believe it, it is sacrosanct.

It is under these set of circumstances – that on one hand siding with Jaramogi’s FORD Kenya made political sense to the Bukusu elite but also went further to give meaning to Masinde’s prophecy in that through Jaramogi, the Bukusu could someday lead Kenya – that Bukusus who belonged to FORD Kenya started bleeding green, black and white – the party’s colours.

This reality therefore meant that whoever led FORD Kenya automatically became king of the Bukusu in the political sense, seen first as Masinde Muliro’s successor then later as Kijana Wamalwa’s substitute. These are conversations that never happen in the open, but are what drove the likes of Mukhisa Kituyi, Musikari Kombo, Eugene Wamalwa, and Moses Masika Wetangula to want to lead the party as a means of winning the hearts and minds of the Bukusu.

It is for this reason that Wetangula used and broke every rule in the book to seize the party.

After the 2007 general election, Mukhisa Kituyi and Musikari Kombo, who were seen as the two thriving original sons of Jaramogi and Muliro found themselves in political limbo after losing their parliamentary seats. The fall was hard, considering before the vote, they were both high flying cabinet ministers. Wetangula, who had joined FORD Kenya late and wasn’t a full minister before the polls, had somehow won re-election and been made Minister for Foreign Affairs.

To Wetangula, it was only natural that he became leader of FORD Kenya, the ultimate prize.

‘‘At one point Musikari Kombo said he wanted to retire from politics, which would have meant him leaving the party to me as earlier agreed,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He then went back on his word on retirement, then started toying with the idea of passing on the burton to Eugene Wamalwa.’’

This, Wetangula wouldn’t agree to.

As an electoral contest was being put in place, Eugene cried foul over Wetangula’s supposed underhand tactics and withdrew from the race – he accused Wetangula of having rigged the vote before the National Delegates Conference (NDC) – while Wetangula accused Eugene of chickening out. Subsequently, Wetangula was elected unopposed as leader of FORD Kenya.

With that, Wetangula was home and dry.

I ask Wetangula why taking over FORD Kenya was so important for him.

‘‘It was very critical to become party leader,’’ he says, ‘‘because you know all serious political activities are centered around parties, and if you want to know how important parties are think of how Kibaki became President as a leader of a party with less than 30 MPs and Wamalwa became Vice President with less than 20 MPs in a National Assembly of 222 members.’’

To Wetangula, if Kibaki and Wamalwa did it with small parties, then why not him?

‘‘I remember sitting with Mwai Kibaki after KANU had imploded and Raila Odinga had led a walk out,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and I heard Kibaki telling Raila and his team, ‘‘Welcome gentlemen, we are now going to be a bigger and formidable team, but remember as you join us, there are two non-negotiable positions – that of flagbearer and that of the Vice President after elections.’’’’

In Wetangula’s view, it took the initial momentum built by small parties to oust KANU in 2002. It is this template that Wetangula believes will be the future of Kenya, with FORD Kenya remaining a common denominator considering majority of the post-1992 parties have lost ground.

As Kenya’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Wetangula started noticing a wind blowing.

‘‘I started seeing a trend where Ministers for Foreign Affairs had either earlier on become or were becoming leaders of their countries,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘Jakaya Kikwete in Tanzania, Hailemariam Desalegn in Ethiopia, Nana Akufo Addo in Ghana, and many others.’’

Out of this, Wetangula too believed he had what it takes to step up and be counted.

‘‘The Ministry of Foreign Affairs gives you international exposure that isn’t available to any other minister,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and you know leading a country is about internal and external relations. Many people have ideas of how to deal with things internally, but external relations are a different ball game altogether. That is what Foreign Ministers bring to the presidency.’’

And so Wetangula shared his intention to contest for the top seat with President Kibaki, who had very little to say – kama unataka, sawa. Wetangula wasn’t disappointed. He didn’t expect much from Kibaki in terms of a public endorsement. And then he noticed Kibaki’s men were rooting for Uhuru Kenyatta. With that, Wetangula opted for CORD, then NASA, and now OKA.

‘‘You don’t have to be big to be a winner,’’ Wetangula says of his small-party big-coalition arithmetics. ‘‘All you need to do is to be part of a big team that supports you.’’

It is out of the same thinking that Wetangula has refused to snub running for a legislative seat, since he considers himself not too big to be a Senator yet not too small to be a principal in a leading national coalition. But what will he do if and or when he becomes President?

‘‘I will make corruption so painful that nobody will dare try,’’ he says. ‘‘I will focus on Uganda and Tanzania and treat them like the first and fifth largest trading partners to Kenya, I will open up the region and create access to the Kiswahili speaking parts of the Congo – Goma, Bunia, Gitembo, Busenyi, because when the regional economy booms, Kenyan businesses blossom.’’

And will FORD Kenya hold its ground seeing other parties have infiltrated Bungoma?

‘‘FORD Kenya is embedded in my peoples’ hearts,’’ he says, ‘‘even those who’ve gone to other parties still come back to me and say huko tumeenda kukaa tu, lakini nyumbani ni FORD Kenya.’’

What about the wrangles rocking the party?

Those are non-issues, Wetangula says.

‘‘Chama kiko imara kama simba.’’

…

This project is a collaboration between

Debunk Media and the Star Newspaper.