Kenya’s Transport Minister Kipchumba Murkomen posted two 2014 loan contracts between Kenya and the Exim Bank of China onto his Twitter account one Sunday evening and got the world talking. The contracts worth US$ 3.2 billion are for the 500 km Mombasa – Nairobi phase of Kenya’s Chinese built Standard Gauge Railway (SGR). Murkomen left out two other loans, worth US$ 1.5 billion more, to build a new inland container depot in Nairobi, and a 120 km SGR extension from Nairobi to Duka Moja.

Partly because of their size, the SGR loans became a holy grail for media and civil society particularly since an infamous live TV incident in December 2018, when Ex-President Uhuru Kenyatta unwisely taunted Kenyan journalist Mark Masai who had the temerity to ask to see the SGR debt contracts.

The Kenyatta government was notoriously secretive and contemptuous of public participation. But Nairobi leaks like a sieve, and it is no secret that so many drinking-in-the-right-places folk have known all the loan terms for a while. Unsurprisingly, the Kenyatta Government’s cagey behaviour spawned a veritable cottage industry within the civil society demanding SGR debt transparency.

Until the 15 September 2022, the Kenyan Government maintained, with a straight face, that it was honour-bound to keep the SGR loan contracts secret from its own principals (the citizens and taxpayers). This purported obligation to conceal was to have effect “in perpetuity”, according to the recently published contracts. So opaque was this transaction, that many came to believe that, Kenya waived sovereign immunity to take the SGR loans and in the event of default has exposed all Kenya’s railways and ports to takeover by China.

Other than the Executive, Parliament too stood indicted. Legislators gave the Kenyatta administration carte blanche latitude, such that shortly after the SGR contracts were tabled in a public hearing before a Parliamentary committee in 2014, no copies of the contracts could be found anywhere by anyone. Several committees in the Senate and the National Assembly simultaneously conducted loud public inquiries into the SGR between 2014 and 2020. The rulebook remained the same. None published the SGR contracts.

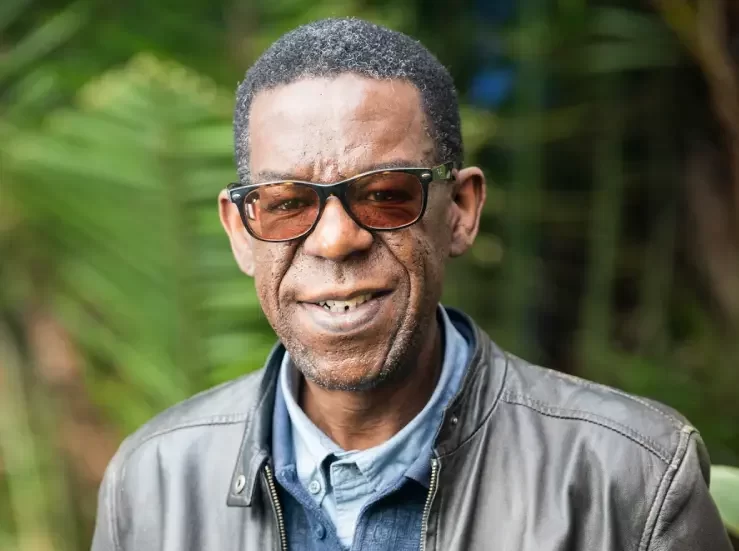

However, the SGR loan documents briefly surfaced in court when an enterprising activist (now Senator) Okiya Okoiti Omtatah filed the SGR contracts in one of his numerous legal battles against the Government. The Government claimed Omtatah stole the contracts from a 2014 committee public hearing which he’d attended, and the Judge readily agreeing with the Government expunged them from court records and dismissed Omtatah’s suit.

On appeal, Omtatah was partly vindicated. The Court of Appeal agreed with Omtatah that the SGR loans violated Kenyan law and were unconstitutional. The Court did not, however, reverse the lower decision that expunged the SGR contracts, reducing Omtatah’s documents to the status of purloined copies which could not be cited anywhere. Rather than assist Omtatah, who’d run out of funds to appeal to the Supreme Court, a large NGO consortium filed a totally fresh case which is still pending before the courts, although they claimed recently to have a court order requiring the Government to publish the SGR contracts.

Foreign debt is a serious issue deserving of serious treatment, and we have collectively not taken it seriously. We have, post-2013, experienced counter-reform until Presidential control over the accountability mechanisms of Parliament is once again pervasive, even as the mainstream media has been progressively dominated by political ownership and subjective gate keeping. Our check and balance institutions address the problems of foreign debt only superficially, episodically and subjectively. As for the civil society, as I have implied in the Omtatah case, things are no different.

Debt is logically assumed to imply control and influence. Likewise grants. China’s supposed rise is at the expense of other creditors. Our leading advocacy NGOs are funded by these other lenders to Kenya. The SGR transparency debate was, to my mind, fueled by a ‘clip China’s wings’ effort by supplanted lenders even though China was only briefly Kenya’s largest foreign creditor having overtaken the World Bank in the year 2016-2017. It is true that before Kenyatta took office in 2013, China’s loan portfolio was no more than 2.5% of total public debt, or 5% of the foreign creditors. It is also true that Kenyatta took Chinese debt from US$ 600 million to over US$ 6 billion by close of business on 9 August 2022.

But it is equally true that post COVID-19 borrowing saw the World Bank surge back to first place in the creditors’ league;in second place are the International Sovereign Bond holders. So, even as we seek transparency for Chinese debt, we must similarly demand for plain language disclosure of the conditions and use attached to all Kenyan debts including the World Bank and IMF loans. The perceptive can see the first effects of the Bretton Woods loan conditions e.g. the end of subsidies on food and fuel, but the Kenyan people should immediately be told the unvarnished truth by their Government about what we have collectively been committed to. Debt transparency must not be restricted to the SGR and Chinese loans.