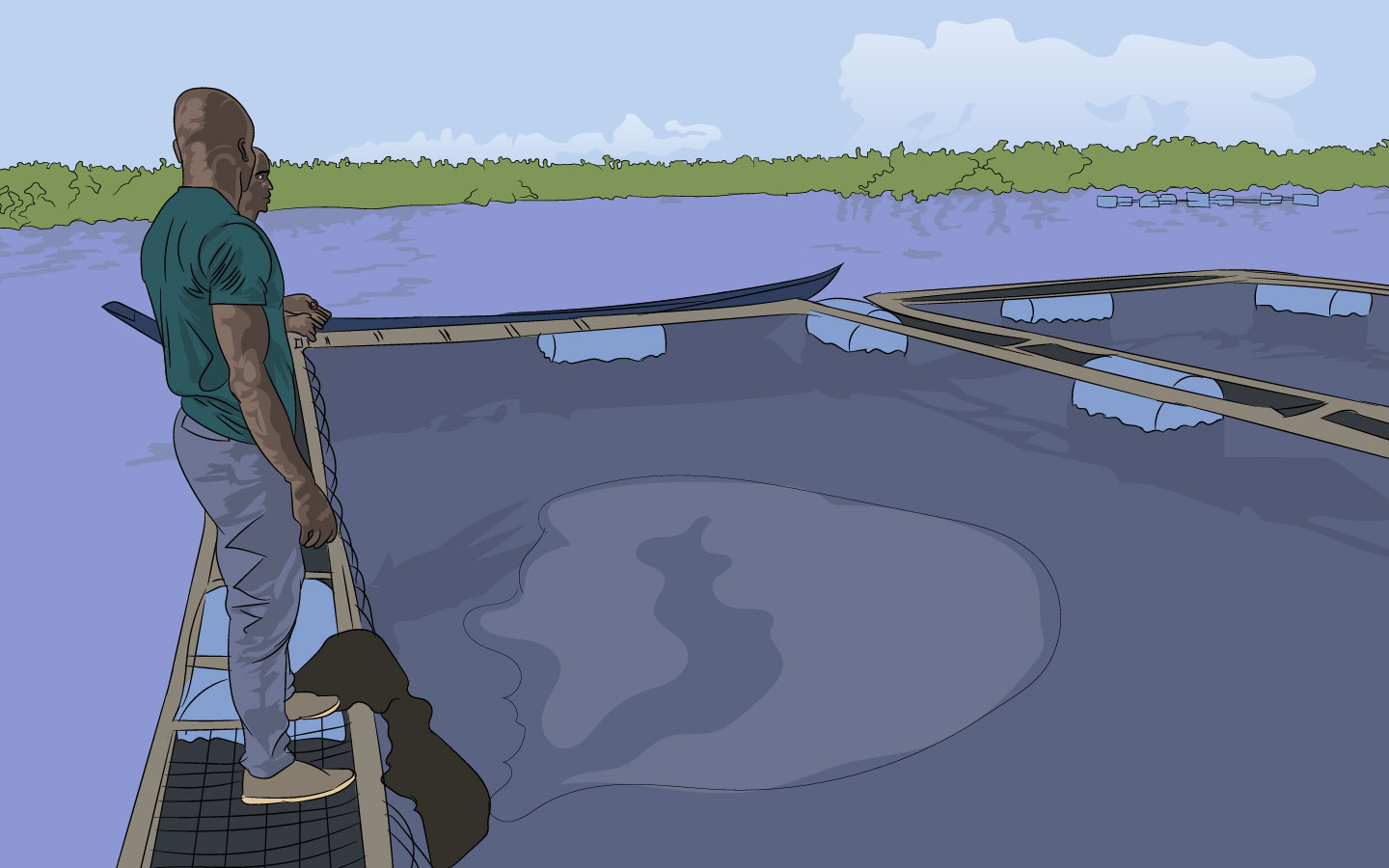

It is 6 o’clock on a chilly Wednesday morning when I meet up with Nick Owiti at Dunga Beach in Kisumu. It has rained all night, and at daybreak, Owiti is getting ready to feed fish in cages located not too far from the shore. I ask if I can accompany him and he agrees. We board a boat with a small outboard engine for the five-minute or so ride to the fish cages. It is just the two of us.

I quickly notice the boat is letting in water – it has a small leakage – but I am not scared. I grew up not too far away from Dunga Beach and have ridden on all kinds of boats, including leaking ones like the one Owiti and I are riding in. I pick up a plastic tin and start draining the water, pouring it back into the Lake Victoria. It is not a lot of work.

Inside the boat is a 45kg sack containing fish feeds. In total, there are 20 cages at the site, but only two belong to Owiti. This morning, it is his turn to feed the fish in all the cages.

“We decided to do most of the operations jointly, despite the cages being owned by different people,’’ Owiti explains. ‘‘It saves on fuel for the boat and manpower.”

As he speaks, Owiti’s voice is partly drowned by the sound of the boat’s engine next to him.

“This is the best time to feed the fish,” Owiti says, almost shouting.

I am seated towards the front of the boat, three rows away from Owiti. I consider it the best spot for achieving balance on the vessel, now that it is not carrying much weight.

“We last fed them last evening,’’ Owiti says. ‘‘They’re very hungry right now, meaning they will eat better. And when they eat well, they mature faster.”

The story of the caged tilapia

The cages, measuring 5m long and going 3m into the water are made of a very thick net attached to a steel frame. Each cage is stocked with 5,000 tilapia fingerlings, but Owiti and his collaborators expect to harvest about 4,000 fish after eight to nine months. They have to make provision for fingerlings which die before maturity, especially the lot that dies in the first few days after they are transferred to the cages. Other fingerlings are lost to disease, but this occurs rarely. At times, death is also caused by underwater currents.

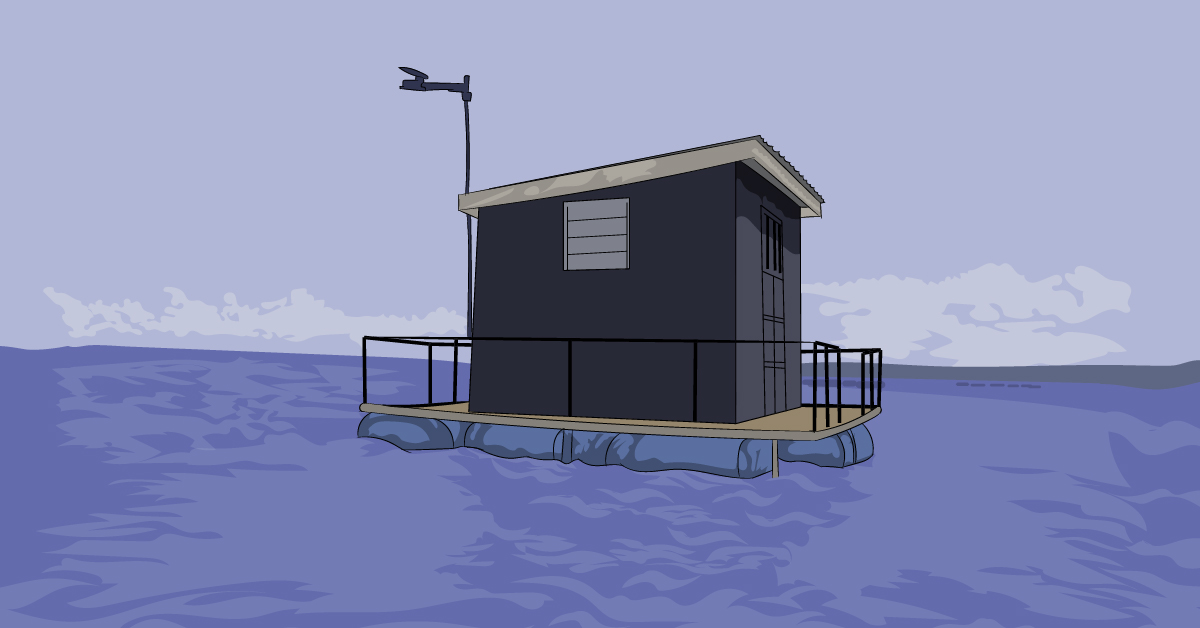

When we arrive at the site, the night guard who has a floating metal house attached to the cages gives Owiti the previous night’s situational report. Other than a few hippos which came close to the cages and had to be driven away, there is nothing much to report. Later on, Owiti tells me that the biggest security risk is human poaching, which usually happens when the fish have matured. Occasionally, crocodiles stray into the area and cause havoc.

“There never used to be crocodiles in this part of the lake,’’ Owiti says, ‘‘but of late they have started making appearances. Recently, one attacked a fisherman in broad daylight. We only found one of his legs.”

In under an hour, we are done feeding the fingerlings and checking the condition of the cages. We are on our way back to shore, with the night guard on board. The cages are visible from the shore, meaning they don’t need vigilant on location guarding during the day.

A fisherman’s fall from grace to grass

Nick Owiti was born on the precincts of Dunga Beach in Kisumu 38 years ago. His father, the late John Didi, was a renowned fisherman in the ‘80s and ‘90s, owning boats at Dunga Beach and also plying his trade in the beaches of Uyoma, Uhanya and Usenge in Siaya.

By the region’s standard’s, Owiti’s father was considered a man of means. He drove a wine-red Chevrolet pick-up truck, reportedly bought brand new from CMC Motors. Possibly motivated by the steady stream of income from his fishing empire, Owiti’s father had at least five wives, and owned a popular pub in Kisumu where famous Luo Benga musicians did live performances, enjoyable especially on the days when the catch from the lake was generous.

However, the one thing that set Owiti’s father apart from the rest of his well to do fisherman was that John Didi gave his children a good education, considering he could afford to send them to boarding schools, which were all the rage back in the day. Most fishermen, despite their fortune, only educated their offspring until Class 8, after which they too went into the at-the-time thriving fishing business.

On his part, Owiti tells me he wanted more than just following on his father’s footsteps and becoming a fisherman, no matter how lucrative it all seemed. He wanted to pursue a career in law or journalism. However, that dream flew out the window in 2003 just after Owiti was done with high school. Owiti’s father’s health had taken a hit, meaning the old man could no longer manage the fishing business ably. Unfortunately, the dozens of relatives employed in the business took the opportunity to pilfer the family fortunes, to everyone’s detriment.

Rising from the ashes

As they say, when it rains it pours.

Unlike in the early to mid 90s when there was plenty of Nile perch, the catch from Lake Victoria had drastically reduced by the early 2000s. This, coupled with the heamorage in Owiti’s father’s business meant that within a short timespan, Owiti’s father could no longer afford to finance Owiti’s education, not to mention that of Owiti’s younger siblings. Owiti had only one way out – to join his elder brother in the wobbly family fishing business.

“Compared to now, the catch was reasonable when I started out, even if not as much as what was caught durng my father’s time’’ Owiti reminisces. ‘‘We still had a bit of Nile perch, but that’s since changed for the worst. Today boats barely come back with anything.”

As fate would have it, Owiti’s father died in 2010, leaving the reins to Owiti’s elder brother. Considering it was impposible to revive the family business since the catch in Lake Victoria had deteriorated, the family resorted to disposing off most of their fishing assets during their father’s illness, leaving Owiti’s elder brother without a reliable source of income to date.

It thus came down to Owiti’s ingenuity, and today he takes care of his younger siblings aside from his own family of three children and a wife, with his eldest just about to sit for KCPE.

“I could no longer cater for my family’s financial needs from fishing alone, not with the dwindling catches,’’ Owiti confides. ‘‘I had to invest a in business and fish farming. Luckily, I learnt about cage farming from a local fisheries co-operative in a project funded by the International Labour Organization (ILO) through the Co-operative Facility for Africa (CoopAfrica). They put up the first ever fish cages in the Kenyan waters of Lake Victoria.”

That’s how Owiti embarked on the journey of cage aquaculture.

Who’s the weakest link?

According to a 2019 publication by Dr. Christopher M. Aura of the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), there were some 4,357 cages of various sizes spread across 31 sites on the Kenyan side of Lake Victoria. While the first cages were installed in 2010, there exists no national policy on cage fish-farming in Kenyan fresh-water bodies 11 years down the line.

“Nile perch has been the backbone of our operations,” says Maurice Ongowe, who has been an official of the Dunga Fishermen’s Co-operative Society (DFCS) for over 30 years now. “In the mid-90s to early 2000s, we would catch a lot of fish, mostly Nile perch. Sometimes up to 8 tonnes of fish would land here in a day. Today if we are lucky, we will have 40kg. That would have been fish from only one boat back then.”

The DFCS, where Ongowe currently serves as secretary, was formed to support fishermen with marketing, savings and credit services. For the longest time – when fortunes were good – the society specialized in the sale of Nile perch, considered the most profitable fish species in Lake Victoria, which was mainly exported. Other popular money-minting species were dagaa (commonly referred to as ‘omena’) and the Nile tilapia (simply referred to as tilapia). Both tilapia and Nile perch are non-indigenous, having been introduced into Lake Victoria in the 1970s, with both species often blamed for the shrinking population of indigenous species.

“The Nile perch had two distinct impacts that contributed to the decline of fish in the lake, including the reduction in its own population,’’ Ongowe explains. ‘‘It was a moneymaker, and when people realized that fishermen were making a kill, a lot of people got into fishing, and made money catching tonnes of these species. The other effect was that this species feeds on other fish, whose numbers obviously dwindled. This affected the lake’s biodiversity.’’

Of the total commercial fish production in Lake Victoria today, Omena accounts for 53.3% of the income, Nile perch 33.4% and tilapia a paltry 4.3%. As Ongowe says, fish stocks have since subsided due to human and environmental factors such as heavy eutrophication, the proliferation of invasive species (like the earlier introduction of Nile perch and tilapia into the ecosystem), over-fishing and the use of illegal/undersize gears. The collapse of local manufacturing also contributed to overfishing, since the lake became the largest.

“In the earlier years, fishing was a sustainable economic activity because not everyone was looking to it,’’ Ongowe tells me. ‘‘We had people working in industries, we had prosperous farmers and we had those working in a thriving public sector. That is not the case today.”

In addition to the economic factors, the government of Kenya previously paid keen attention to the Lake Victoria resource. Policies such as the ban on fishing activities between April and August each year allowed the lake to restock, since this is usually the breeding period. There were even zones where fishing activities were prohibited, like river mouths, which are fish breeding areas. The government also regulated the kind of fishing gears used.

While the ban on fishing during the breeding season no longer exists, the other policies that should promote sustainable fishing practices are poorly implemented. Fishermen using illegal gear that harvest small fish and fish eggs easily bribe their way out of custody when arrested.

The prohibitive costs of caging fish

Seeing that everything around the Lake Victoria fishing ecosystem was crumbling, the Dunga Fishing Co-operative Society (DFCS) therefore came up with the cage aquaculture project as a possible solution to the problem of reduced earnings from fishing activities. But as Owiti points out to me during our early morning visit to the fish cages just off Dunga Beach, this kind of fish farming is a venture that is still out of range for most traditional fishermen.

“I spent about Ksh. 340,000 per cage during my first venture,’’ Owiti says. ‘‘Even though the construction of cages is an expensive affair and you get to recoup your investment with time, the initial capital is what remains prohibitive to your average fisherman.”

Maurice Ongowe, the DFCS secretary thinks that the government should develop policies to guide cage aquaculture in Lake Victoria, with the aim of empowering local fishermen.

“In 2010/2011 President Mwai Kibaki introduced a stimulus package for aquaculture,’’ Ongowe says. ‘‘It failed to pick up here because most fishermen were used to capture fisheries. Now that we have learnt a thing or two about cage fish farming, this is an area where the government can come in and support fishermen through co-operative societies. Because of the huge sums required, a group investment approach is more sensible.’’

Aquaculture’s imperfections

And yet this is not just a Dunga Beach problem. The decline in catches is replicated across Lake Victoria, with fishermen continuing to suffer. The picture is made muddier by the reality that even though cage aquaculture is a viable option, it cannot be the only way out. This is because according to Dr. Christopher M. Aura’s 2019 paper on cage aquaculture in Lake Victoria, only 4.7% of Kenyan waters have suitable sites for cage farming. This can only take 25,427 cages with a production of 20,000 tonnes of tilapia annually, which will not be adequate supply in meeting the always growing demands for the fish species.

Further, experts warn of the negative impacts of uncontrolled investment in cage aquaculture due to concerns over the rise of environmental degradation. This pollution comes from the discharge of particulate and dissolved nutrients such as uneaten waste feed, faecal matter and excretory products which are bound to negatively impact the fishery environment by causing anoxic conditions in sediments underlying the cages. This eventually leads to changes in the abundance and composition of microorganisms in the lake.

There is need to look back to the past and reinstate the good fishing practices carried out in the lake in the 80s and 90s if freshwater fishing (of which Lake Victoria accounts for 80%) is to regain its lost position in our economy. Because the lake is a shared resource, some of these efforts will need to be harmonized across Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. There is also need for the revival of industries in the Lake region the pressure currently being exerted on the lake’s resources.

The lucky early birds

As Owiti and I settle in back on shore, it is clear to me that his is not the common story, since majority of local fishermen do not own and may never own fish cages around Lake Victoria, considering most of the cages on the lake are owned by investors from outside the fishing villages. To these investors who can afford the high costs of setting up and maintaining a successful cage aquaculture venture, it is all business and not necessary about the locals.

For all his troubles, Owiti will be harvesting his fish in December 2021, hoping to get an average of Ksh. 600,000 from each cage, enough money to take his son to high school next year.

“I am a third or fourth generation fisherman,’’ Owiti tells me as he sees me off. ‘‘I want something different for my children. Maybe one day one of them will be an accountant, a lawyer or a journalist like you.”