Common sense (at least the one we know) making budget cuts is a sure way of reducing debt pile up, but according to the Treasury Cabinet Secretary Amb. Ukur Yatani, what Kenya needs now as it wallows in debt is a raise of its debt ceiling. As if that’s not enough, the Treasury has proposed that Kenya should completely discard its debt ceiling and cap debt as a percentage of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the sum of all goods and services produced in a country in a specific time period.

The Backstory: Over the years, Kenya’s debt has been rising at an increasingly rapid pace. When the current administration under President Uhuru Kenyatta and his Deputy William Ruto, came into power, Kenya’s gross public debt was at approximately 1.7 trillion. But as of December 2021, that figure has risen to approximately 8.2 trillion – comprising 50.9% external debt and 49.1% domestic debt against the country’s nominal GDP estimated at Sh10.7 trillion.

The Explanation: According to the treasury, the increase in public debt is attributable to external loan disbursements, exchange rate fluctuations, and an uptake of domestic debt. And although the increasing debt has raised alarm, instead of triggering triage from the government side, the response has been to borrow some more. In the August 2021 Budget Outturn, the Kshs 162.4 billion went towards debt servicing, against collected revenue of Kshs 247.2 billion, amounting to a 64.7% debt service. Increase in debt servicing expenses has outpaced the allocations for development expenditure-for which debt is meant to finance.

The debt ceiling, for beginners: The debt ceiling, set by law, is a limit on the amount the government can legally hold in debt. The limit is put in place to ensure that the government maintains its debt without abdicating its obligations to the people and its lenders. When the government surpasses the debt ceiling, the government may be forced to either raise the ceiling or rely only on incoming revenue. If the revenue isn’t enough, the government then must choose between serving its citizens or honouring its debt obligations. Kenya’s statutory debt ceiling is currently set at Ksh 9 trillion.

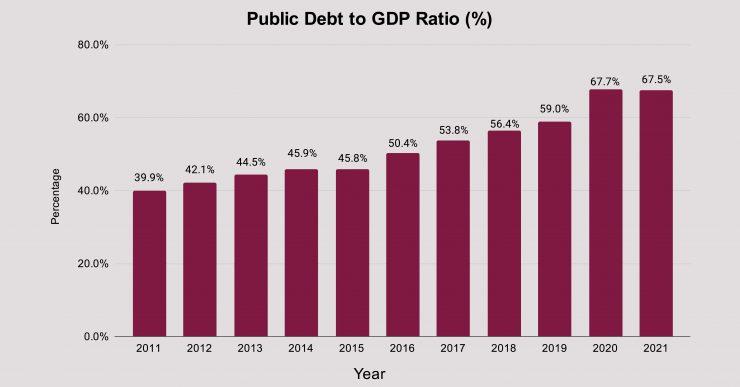

Amending the debt ceiling: In 2019, parliament (the National Assembly and Senate) amended the Public Finance Management regulations to increase the country’s debt limit from 50 percent of GDP to the numerical figure of Ksh 9 trillion. In 2021, again, the National Treasury embarked on a bid to have parliament expand the statutory debt limit to cater to the budget deficit in the financial year 2021-22 and the preceding years. However this never came to fruition. Now, the national treasury would like to cap the limit at 55 percent of GDP, which goes against The International Monetary Fund recommendations that ratios of public debt to GDP should not be higher than 40% for developing countries.

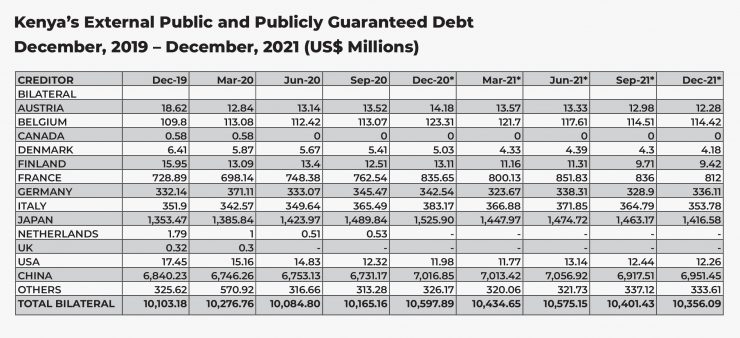

Who does Kenya owe?: China and Japan are the largest bilateral creditors to Kenya with their respective debt stocks standing at $6.9 billion and $1.4 billion respectively.

The Conundrum: External debt is not necessarily harmful for an economy, however, interest and principal repayments on external debt are made in foreign currency. This depletes a country’s foreign exchange reserves and may devalue the domestic currency. A weak currency can lead to high inflation rates in the long term because it costs the country more to import what it needs for production and consumption. This inflationary effect is bad for a country like Kenya, which imports more goods and services than it exports. As it stands, more than half of Kenya’s total debt is held in foreign currencies, presenting an imminent fiscal risk should the shilling depreciate.

Similar to bilateral agreements, Kenya’s four Eurobonds-with a fifth one on the way- continue to saddle its external debt register.

- 2021: $1 billion, at an interest rate of 6.3 percent for the 12-year Eurobond

- 2019: $2.1 billion, in two tranches of $900 million at seven percent for a seven-year paper and eight percent for a 12-year, $1.2 billion tranche.

- 2018: $2 billion in two equal tranches of $1 billion, paying 7.25 percent for the 10-year paper and 8.25 percent for the 30-year option.

- 2014: $2 billion Eurobond in two tranches of $1.5 billion over 10 years and a five-year $500 million bond.

Damned if we do. Damned if we don’t!: Parliament’s Budget Office forecasts that by the end of June 2022 the stock of debt will range between Ksh Sh8.6 trillion and KShs 8.8 trillion-crossing the 10 million mark in 2024-which means the only amount the government can borrow in the next financial year without amending the ceiling will be approximately KShs 400 billion. With a fiscal deficit of KShs 846 billion for the financial year 2022/2023, this may be next to impossible.

In the recent past, the Parliament Budget Office has argued against the debt ceiling, claiming that its role in debt management is weak since the cap is more of a legal limit and not an indicator of sustainability- It is “ numerical limit, arbitrarily set, and delinked from macroeconomic factors that determine the debt carrying capacity of a country, alongside other factors”, they say.

The debt ceiling being an arbitrary figure does not restrain national debt- raising the debt ceiling simply lets the government pay for things it has already decided to spend on- that lies primarily in the hands of the government to curb its spending.