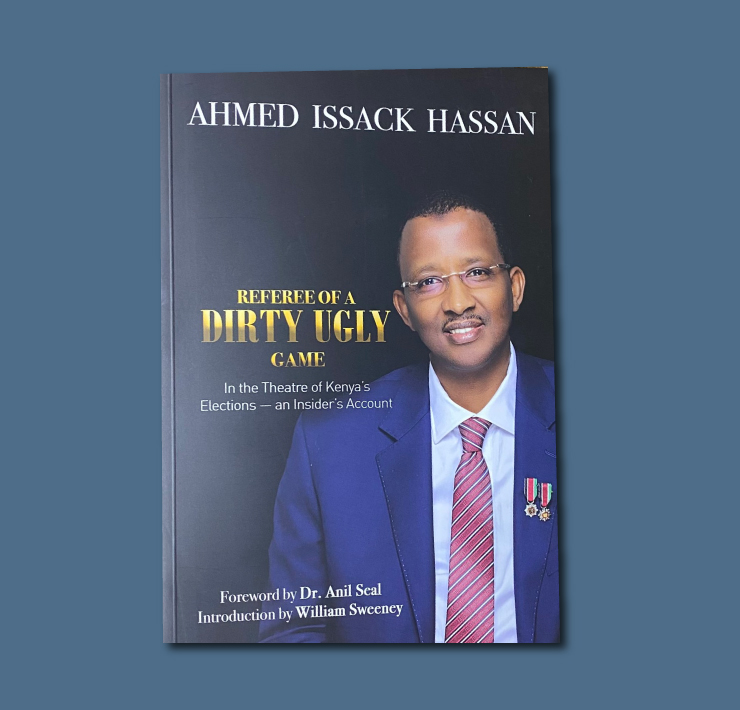

Ahmed Issack Hassan, the former chief of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) has written his memoirs (more of an expose in my view) of his tenure in a newly published book Referee of a Dirty Ugly Game. This is a must-read for anyone who is interested in understanding the gang-ho political on-goings of our electoral processes. Indeed, the book informs on similar happenings of other electoral jurisdictions beyond our borders. I will not attempt to do a review of the book nor offer any critique. However, I am more interested in the import of some of the issues Hassan has raised regarding the management of electoral processes and the whole conversation about the (ir)relevance of elections especially in a country like ours.

The first question that came to mind after putting the book down was on who owned the electoral process in Kenya. The assumption that has been codified in our legal documents, including the Constitution, is that the people of Kenya, through the wishes expressed by those who turn out to vote (not just registered) are the real owners and therefore beneficiaries of the electoral process.

It is thus expected that such owners of the process would reap big at the end of it all through by identifying leaders who would then go ahead to form government and basically formulate policies and interventions whose effect would be to improve livelihoods. Reading between the lines (always good to do) of Hassan’s book indicates otherwise. The intrigues and power play that are involved in the appointment of IEBC Commissioners, the interference with decision making processes of what ideally should be an independent agency and the elite’s impassioned interest in the electoral outcomes is indicative of a different ownership than the one anticipated by the framers of our laws.

The book highlights the high-level political negotiations that are undertaken just to decide on who becomes a member of the commission and the top officials of the secretariat. These negotiations take on regional, political, ethnic, and even fraternity associations aspects. One must get the blessings of these associations to even make a cut for consideration. It involves shuttling from one office to another, meeting top political leaders, key door-openers (including brutes) and opinion leaders. It is a process filled with apprehension, conspiracy, and intrigue. Friends become foes and foes turn into allies. Such are the uncertainties and tensions, to a point where the former chairperson’s mother consistently comes into the picture urging him (throughout his tenure) to disengage from the ‘dirty, ugly process’. Hassan’s mother was finally granted her wish when the entire Commission was hounded out of office in 2016 after a famous ‘settlement’ (between Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta) and resolution of the political stalemate initiated by those unhappy with the Commission’s performance.

Interestingly, this power play did not stop after appointment into the Commission. Splits and cracks within the Commission began almost immediately after they assumed office. This manifested itself in how critical decisions were made on such things as procurement (money matters) and critical electoral processes such as voter registration and results transmission (power matters). However, the best illustration of the splits in the Commission remains the 2022 Bomas of Kenya results declaration episode, with vice chairperson Juliana Cherera leading a team of four at the Serena Hotel in denouncing chairman Wafula Chebukati’s numbers. Hassan’s book confirms that such divisions were the norm since the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) days with Samuel Kivuitu at the helm.

Perhaps the most disturbing issue that comes out of the book is the vicious vilification, personalized attacks, and threats to life of the top officials of the election management body. Indeed, several top IEBC officials, key among them Chris Msando, have gone on to lose their lives in unsolved murders that have left their families devastated. Yet the contestations over the electoral commission remain. Yet our politics has remained the same. Yet the political leaders are still largely the same gang. Is it any wonder then that with all these shenanigans, disputes over the electoral outcomes also remain?

In my view, Hassan’s book offers Kenya as a country an opportunity to reflect on how not to run the next election(s). It offers an opportunity to review the entire process starting from the legal regime to the appointment of commissioners, the Commission’s management and the conduct of the elections.

Certainly, a business as usual attitude will change nothing, given that political actors have already initiated another process of appointing new commissioners using the same corridors that are based on vested interests and power play irrespective of the laid down procedures prescribed by established laws. I feel this is still on the same slippery slope that we have been used to and therefore chances are that nothing much will change.

We can take cue from some of the recommendations that have been given by Hassan, a critical one being the need to change our political and electoral system. It has a simple argument. Kenyans seem to have no problem with the other five political seats apart from the presidency. Despite a few successful petitions here and there, it is clear even from a historical and statistical point of view that over 90 percent of non-presidential elections are not in conflict or controversial. Therein lies our answer. Why not then delegate the decision of who becomes the supremo of the country to these elected members. Governors can be elected by Members of the County Assembly (MCA) so that they can be accountable to them. Voters would then elect the Senator themselves both for oversight of the county as well as representation in the national parliament. Members of the Parliament (MPs) elected by the people would then have the unenviable responsibility to then choose the president of the country. Based on their numbers and political affiliations, this will become more predictable over time.

The investment would therefore be in getting MPs who can choose the right leader. Accountability would then be on two levels; at the parliamentary level and at the people level for the parliamentarians. Hassan may have had his faults, but we can learn a thing or two from his experience.